The news moves quickly — especially when it comes to environmental issues, which despite the threat of climate change still tend to get overlooked by major media outlets. We know how easy it is to miss critical stories and not be able to see the forest for the trees, so we’ve collected some of the best and worst news stories for the month, connected the dots to reveal a few trends, located updates to ongoing stories, and uncovered some new science and important transitions you won’t want to miss.

Welcome to Links From the Brink.

Best News of the Month: Keystone XL is kaput. TC Energy, the company behind the notorious pipeline, pulled the plug this month following more than a decade of protests. President Biden cancelled the pipeline’s permit a few hours after he took office, and that appears to have finally been TC’s signal to stop trying. It took ‘em nearly five months to admit defeat — even for a corporation, it’s hard to give up on your dreams.

Will similar, ongoing protests at the Line 3 pipeline have the same result? We live in hope — and also hope more protestors don’t get injured along the way (because things are escalating badly).

Finally, the U.S. Border Patrol is doing what it’s supposed to do: defend Canadian oil assets from Native Americans

— Emily Atkin (@emorwee) June 7, 2021

Worst News of the Month: Carbon dioxide levels reached another new high in 2020, capping out at 419 parts per million. This might seem shocking, since global greenhouse gas emissions famously fell 6% last year as a result of the pandemic, but it reflects all CO2 released over the years — gases that don’t just go away the minute we stop burning fossil fuels.

“We still have a long way to go to halt the rise, as each year more CO2 piles up in the atmosphere,” geochemist Ralph Keeling said in a statement. “We ultimately need cuts that are much larger and sustained longer than the COVID-related shutdowns of 2020.”

And imagine how much worse off we’d be if Keystone XL hadn’t been cancelled — or if Line 3 isn’t.

It’s All Connected: Stopping pipelines is great, but a new United Nations report warns that if we want to save the planet we need to address the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

It’s great to see both these threats being addressed at the same time. Now if only President Biden’s next budget would address the extinction crisis…

(Oh, and on a related note, the UN also declared the next 10 years the “decade of ecosystem restoration.”)

The Missing Link … of Death: We’ve covered the dangers of rodenticides a few times here at The Revelator, most recently linking the poisons to the deaths of endangered wildlife in the United States. Well, Americans aren’t the only ones overusing these deadly concoctions. A new study out of Tasmania finds a frightening level of rodenticide-related deaths of wedge-tailed eagles — one of the Australian island’s apex predators.

Here’s the twist: Wedge-tailed eagles don’t eat rodents. They eat animals that eat rodents, which means the poisons are traveling up the food chain all the way to the top. The study didn’t identify which animals served as the missing link, but smaller birds like ravens could be the carriers.

The study found high levels of a rat poison called brodifacoum in dead eagles, as well as flocoumafen, an agricultural pest-control toxin that’s part of a group of chemicals called “second-generation poisons” that kill with a single dose. But while these second-generation poisons are quite fatal to rats, death isn’t instantaneous. “Because these poisons take a while to kill the rodents, the rodents can…eat far more poison than they actually need to kill themselves,” Birdlife Australia raptor specialist Nick Mooney told the Australian Broadcasting Company. This makes the rats themselves super-toxic (and deadly) to anything that eats them. “They’re little walking time bombs,” he said.

The problem isn’t limited to the island of Tasmania. Over on mainland Australia, dozens of owls have been found dead over the past 18 months, and autopsies revealed internal bleeding from wounds that should have healed. Second-generation rodenticides are anticoagulants, so scientists suspect the poisons caused these deaths as well.

And tragically, as scientists warn at The Conversation, this could just be the start of more to come.

Food for Thought? Intensive human contact correlates with smaller brains.

OK, this isn’t a general statement (although it kind of feels that way). It’s research about how centuries of husbandry have reduced the size of the brains in various cattle breeds. Still, it speaks volumes — and raises novel ethical questions about the ways we raise our food.

The Bright, It Burns: Our Google News Alerts about light pollution were operating in overdrive this month. Here are just a few of the recent headlines:

-

- Young Clownfish Likely to Die Faster When Exposed to Artificial Light, Study Finds

- Noise and Light Pollution Changes Which Species of Birds Visit Our Backyards

- Fireflies Need Dark Nights for Their Summer Light Shows – Here’s How You Can Help

- Turning Off Half of City Lights at Night Could Cut Bird Mortality By Up to 60 Percent

- Dark Sky Havens: Where Can I Find One?

- Orbital Debris Creates a New Problem: Light Pollution

That last one about orbital debris — maybe the solution involves not putting up so many satellites to begin with. Could NEPA, an environmental law normally applied to terrestrial problems, provide a tool to do just that?

You can find our previous coverage on light pollution here.

Meow Max: Last year I wrote about the threat feral cats pose to Hawaii’s unique species. Well, things have gotten even worse in the past 12 months, as the pandemic slowed down the state’s trap and sterilization efforts. Now experts worry that hungry cat populations will have a baby boom, which could push native species even closer to extinction.

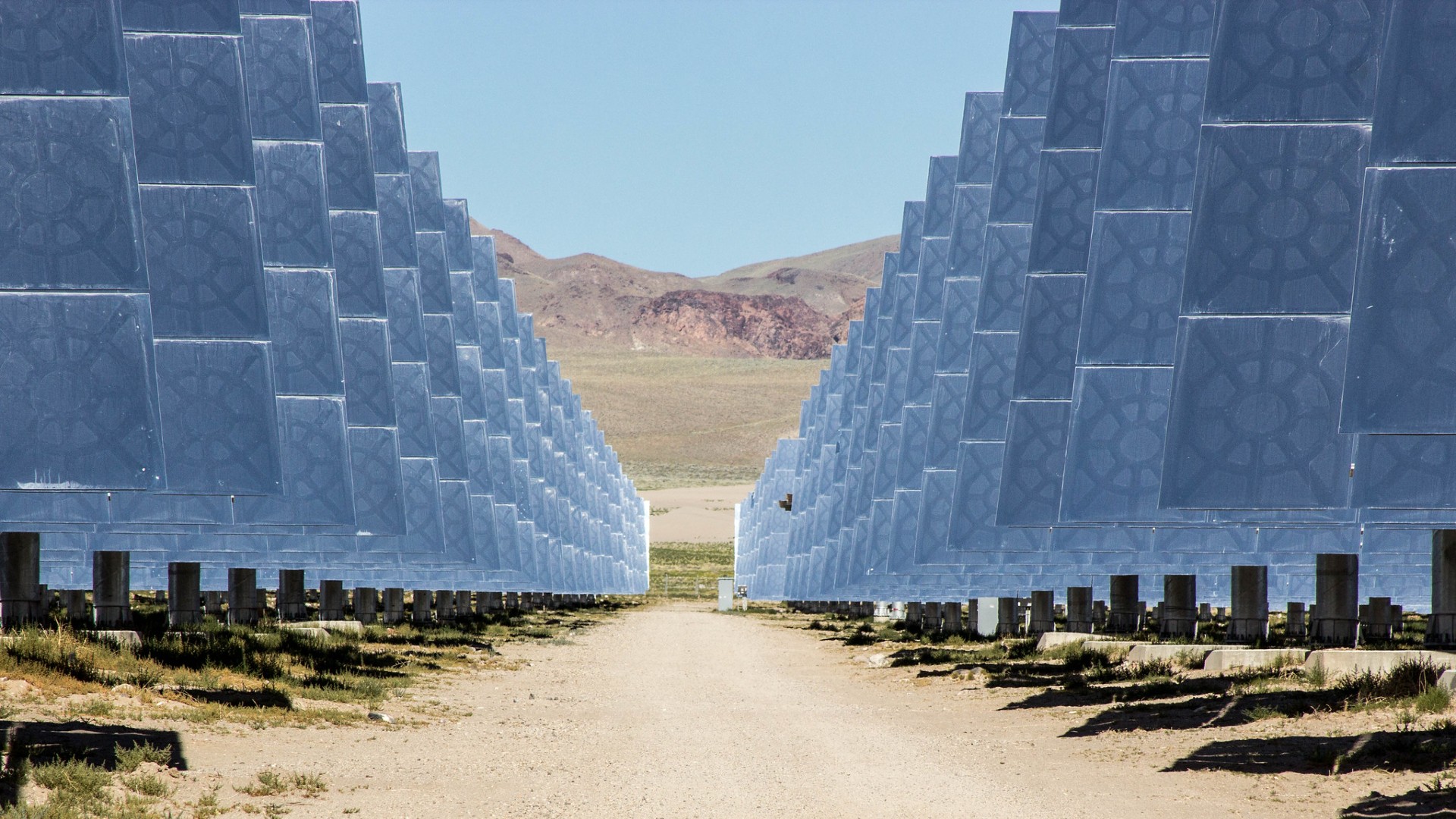

Renewables on the Rise: The United States consumed (good word, BTW) a record level of renewable energy in 2020 — 11.6 quadrillion BTUs, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. That’s 12% of U.S. energy consumption: way too low, but still progress.

And that progress will continue: New solar installations are projected to increase 24% this year, although the industry faces supply-chain issues and a tight labor market that could limit further growth.

Meanwhile, new research from the International Renewable Energy Agency finds that the renewable energy generation installed in 2020 delivers power cheaper than coal.

But don’t count the coal industry out quite yet. So far this year the United States has actually produced 9.5% more coal than it did by this point last year, according to data released June 24 by the EIA. (Sigh…)

City of Amphibians: Los Angeles just published a list of 37 “umbrella indicator species” that reside within the city limits, along with a plan to monitor them. The list includes Baja California tree frogs, great blue herons, mountain lions, North American Jerusalem crickets and — of course — bumblebees. If these species thrive, it will serve as a sign that the city is keeping its natural spaces healthy and connected. To find out how they’re doing, the city will post species observations on citizen-science platforms like iNaturalist, which they hope will also help keep residents engaged about their local wildlife and public spaces.

This appears to be the first list or program of its kind. Hopefully it can serve as a model for other metropolitan areas.

If you’re in the Los Angeles area, the public can participate in monitoring during (and presumably after) the L.A. Bioblitz Challenge that runs through Aug. 7 — just don’t get too close to those mountain lions.

Heartbreaker: Why a dying U.S. Army veteran keeps fighting to end the toxic military burn pits that, in all likelihood, caused his terminal cancer — even as he shops for his own coffin.

Lawbreaker? Will ecocide join the ranks of genocide and war crimes at the International Criminal Court? A new draft law defines ecocide as “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts.” It will take at least four years for this proposal to become official law, and it will have to jump several hurdles along the way, but hey, that gives certain corporations (you know who you are) plenty of time to line up their defense attorneys…

The moment you’ve been waiting for! Today the expert drafting panel convened by the Stop Ecocide Foundation reveals the result of 6 months of legal deliberations: their proposed definition of #ECOCIDE as a fifth crime under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. pic.twitter.com/mMA6U58wA4

— Stop Ecocide International (@EcocideLaw) June 22, 2021

What’s Next? July is already shaping up to be quite a month, with continued drought and record heatwaves, a potential wolf slaughter in Idaho, and more protests over Line 3 — not to mention showdowns over voting rights, infrastructure and so much more that will affect environmental issues for years to come.

What are you watching or waiting for in the months ahead? Good news or bad, drop us a line anytime.

That does it for this inaugural edition of Links From the Brink. For more environmental news throughout the month, including bigger stories you won’t find anywhere else, subscribe to the Revelator newsletter or follow us on Facebook or Twitter.

![]()

These marmosets live mainly in the Atlantic forest fragments in the states of Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais, in southeastern Brazil. They range from south of the Rio Doce in Minas Gerais into the mountainous region of Espírito Santo state. The southernmost part of the species’ range extends west into eastern Minas Gerais, where it’s found in scattered localities in the Rio Manhuaçu basin as far as the Manhuaçu municipality.

These marmosets live mainly in the Atlantic forest fragments in the states of Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais, in southeastern Brazil. They range from south of the Rio Doce in Minas Gerais into the mountainous region of Espírito Santo state. The southernmost part of the species’ range extends west into eastern Minas Gerais, where it’s found in scattered localities in the Rio Manhuaçu basin as far as the Manhuaçu municipality.