Links — the connective tissue that binds us all together.

The brink — the edge of something you don’t want to fall over, or a tipping point we can be pulled back from just in the nick of time.

As the world burns (or floods), too many stories slip through the cracks. We’ve collected some of the most important stories you may have missed — and connected the dots to bigger trends and issues along the way.

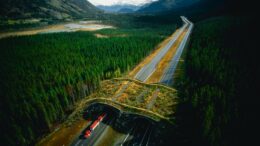

Best News of the Month: Put down those chainsaws. The Biden administration this month proposed restoring protections to nine million acres of the Tongass National Forest in Alaska, the latest in a thankfully long list of reversals of Trump-era policies. That’s great news by and of itself, but the Biden team went even further and moved to end large-scale old-growth logging within Tongass, while also adding $25 million to fund new sustainable development projects in Alaska. This would protect about 400 species in the region as well as people worldwide, since the forest serves as a one of the world’s largest carbon sinks. (That last part is especially important now that Amazon deforestation has flipped that region from a climate sink to a climate emissions source.)

I’m Gonna Wash That Trump Right Out of My Hair: Speaking of Trump policy reversals, the standard for low-flow showerheads that the previous president flushed away is now on its way back to our bathrooms.

Trump’s standard rollback in this case was the watery equivalent of “rolling coal” — it was purposefully wasteful and done just out of spite. Luckily, consumers and corporations never agreed with this approach. Virtually all showerheads currently on the market already conform to or beat the old standard, which we expect will officially be in place again in a few months.

Worst News of the Month: In the latest in a long line of what can only be described as systemic failures, the government of Mexico announced it will once again allow fishing within the critically endangered vaquita’s habitat.

This ends the six-year-old “no-tolerance zone” that blocked fishing with the waters necessary for vaquita survival. With as few as nine of these porpoises left in the Gulf of California, and a long history of the animals dying in fishing nets, this change in policy could amount to a death sentence and eventual extinction.

Of course, things have been dire for the vaquita for two decades, and the species still manages to hang on. We can only hope that remains the case long enough for international pressure to force Mexico to change its mind once again.

View this post on Instagram

This Contradiction Makes My Brain Hurt:

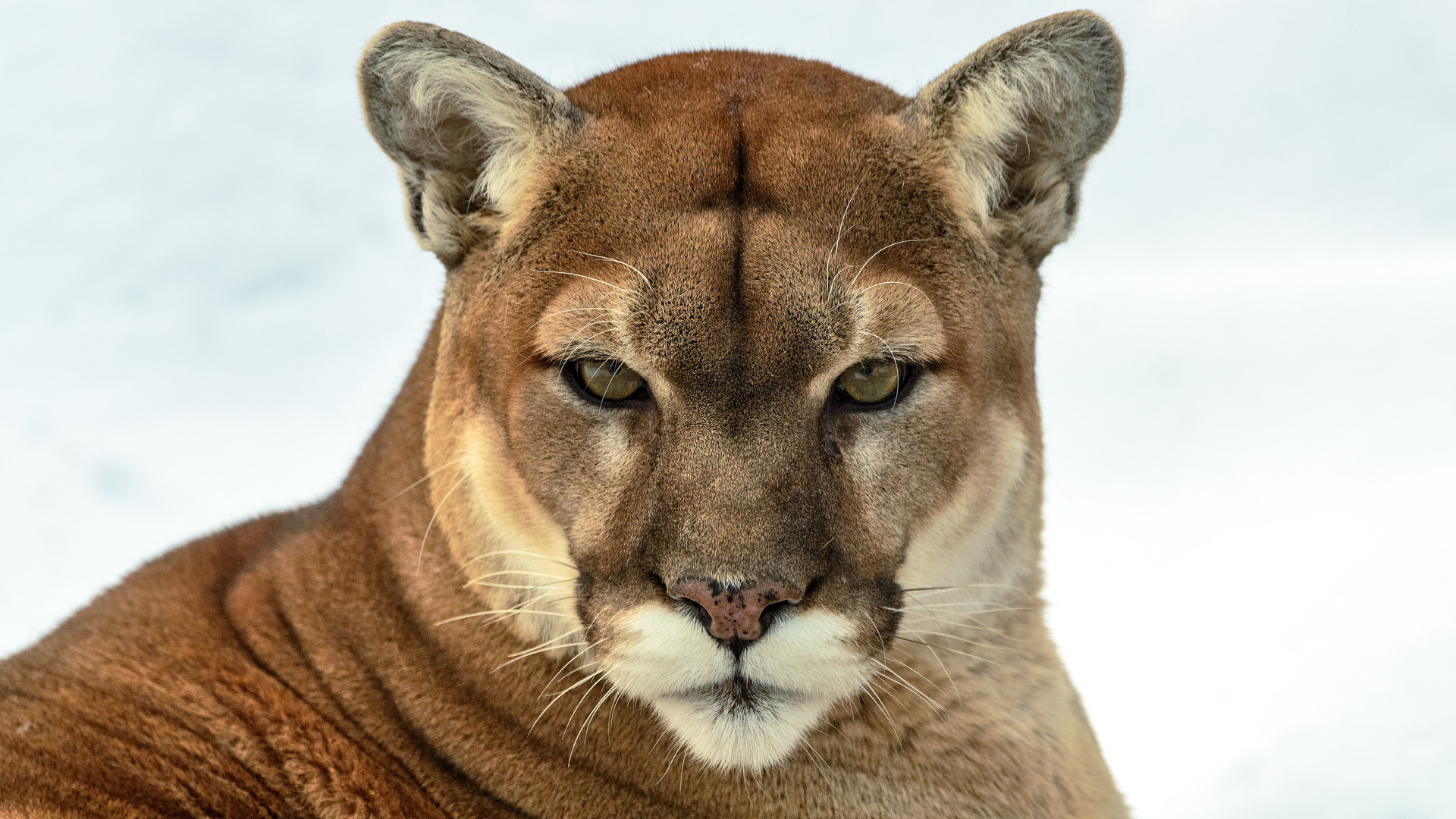

What’s in a Name? Mountain lion, puma, panther, catamount … these names — and 78 others — are all commonly used to describe the same species, the big cat known scientifically as Puma concolor. New research finds that those wide and varied names “can obscure or deflect conservation communication,” making it harder to generate and maintain public interest in protecting these important predators (whatever you call them).

Speaking of Panthers: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed opening Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge to “off-road vehicles, mountain bikes, camping, fishing, drone-flying, commercial filmmaking, commercial tour groups, and, for three weekends a year, turkey hunting.” Journalist Craig Pittman (who literally wrote the book on Florida panthers) says the move is “not as bad as building golf courses in state parks, but it’s close.”

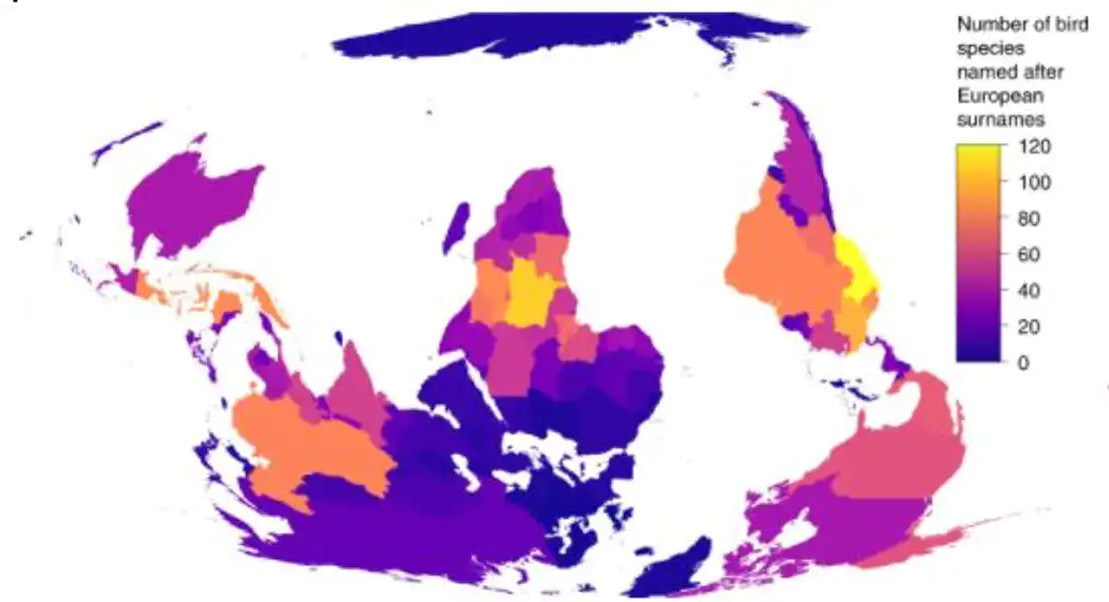

What’s in a Name, Part II: The push to decolonize species names made some key advances this month. The Entomological Society of America launched its Better Common Names Project to “review and replace insect common names that may be inappropriate or offensive.” Case in point: the gypsy moth, which is named after a slur against the Romani people.

Separately, Minnesota state Sen. Foung Hawj initiated an effort to rebrand the four species known as “Asian carp” plaguing the region to “invasive carp.” This is not a new idea, and it hasn’t been accepted in scientific circles yet, but it’s a welcome move in an era with so many hate crimes against Asian-Americans.

Meanwhile, in Oregon, an extinct saber-toothed cat species has been named Machairodus lahayishupup, with the second half of the taxonomic name using the words for “ancient wild cat” from the language of the Cayuse people, on whose ancestral lands the fossils were found. There are no fluent speakers of the Cayuse language today, so this name “gives the community an identity and recognizes the contributions of early generations of Cayuse people,” linguist Phillip Cash Cash, Cayuse-Nez Perce, told Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Richard Branson Can F*** Himself, and Jeff Bezos Can Put His Rocket Where the Sun Don’t Shine: It seemed like all the TV networks fell for the enormous PR stunts of rich people catapulting themselves into “space” this month. Few reported on the most shameful aspect of these missions: their terrible consequences for the planet.

“One Virgin Galactic launch produces >30 tons of carbon dioxide,” climate scientist Peter Gleick wrote on Twitter. “7x more than the average human produces in a year; twice what the average American produces in a year. Enjoy your 4 minutes of weightlessness.”

For the most part the true cost of these brief trips to our outer atmosphere did not attract much oxygen from the broader media. Heck, CNN even bumped climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe from a planned appearance in order to cover “breaking news” about Sir Richard Branson’s launch.

And it got worse from there. In the days after his flight, Branson himself doubled down on his excess, telling late-night TV host Stephen Colbert that critics calling for him to invest his billions into combatting climate change weren’t “fully educated” about space travel — a discussion the right-wing media leapt upon almost immediately as a way to criticize the “woke warriors” on the left.

Okay, culture wars aside, we agree with Branson on one point: Space travel and technology are — in many ways — essential to this modern world. We wouldn’t, for example, be able to monitor the damage we’re doing to the planet without space-based satellites and sensors. But do we need to do more damage along the way for a mission that accomplishes nothing scientific or practical? Even Jeff Bezos acknowledges that we don’t — not that that stopped him.

The Maine Event: The Pine Tree State made innovative progress on three critical environmental issues recently. First, Maine required its pension system and state treasury to divest from the fossil-fuel industry over the next five years, a move that will put at least $1.3 billion of investments into more climate-friendly industries. Activists say other states should follow this model.

The Maine Event: The Pine Tree State made innovative progress on three critical environmental issues recently. First, Maine required its pension system and state treasury to divest from the fossil-fuel industry over the next five years, a move that will put at least $1.3 billion of investments into more climate-friendly industries. Activists say other states should follow this model.

After that, Maine became the first state to ban PFAS “forever chemicals” in products (effective in 2030), a move strongly associated with the state’s famous/infamous paper mills. It also passed the first law extending producer responsibility law, requiring big corporations to pony up for the recycling of their own packaging.

Unfortunately Maine failed on two other major fronts. Gov. Janet Mills signed a law banning wind farms in state waters (forcing them further offshore) and vetoed legislation to shift its electricity networks to community ownership, a move proponents said would have further sped up the transition to renewable energy.

Unexpected Conservationist of the Month: Cartoonist Matthew Inman, better known as the mind behind The Oatmeal and books like How to Tell If Your Cat Is Plotting to Kill You, turned in a hilarious comic strip about wombats, focusing (rightly so) on their square poop and evolutionarily marvelous butts.

But that’s not all: When he published the strip, Inman also donated $10,000 to wombat conservation (that averages out to about $1k per poop joke) and provided resources for others to follow in his footsteps. With as few as 80 northern hairy-nosed wombats remaining, every dollar (and poop joke) counts.

What’s Next? August will undoubtedly see more tragic fires, floods and destruction. Will the month also bring any action on the infrastructure bill, which may or may not end up containing legislation to address climate change? We’ll be watching this topic closely.

We also expect the arrival of the next climate assessment from the IPCC, more action on voting rights (which strongly affect environmental legislative outcomes), and news about wolves. We’ll also celebrate Cycle to Work Day on Aug. 6 and World Elephant Day on Aug. 12.

What are you watching or waiting for in the months ahead? Good news or bad, drop us a line anytime.

That does it for this edition of Links From the Brink. For more environmental news throughout the month, including bigger stories you won’t find anywhere else, subscribe to the Revelator newsletter or follow us on Facebook or Twitter.

![]()

When we found the bobolink’s tuxedoed back and rambling song rising from the fields alongside the dirt road leading to our campground, we knew we’d arrived just where we should be — and right on time. This moment marked not merely the end of our drive but also the bobolink’s astounding feat of flying over 12,000 miles since we’d last heard his call. Bobolinks, who tend to be seen singly, attested to the braiding of wings and land and sea, to the astonishing rhythm of spring’s abundances, and to the persistent migrations of birds, songs and birders.

When we found the bobolink’s tuxedoed back and rambling song rising from the fields alongside the dirt road leading to our campground, we knew we’d arrived just where we should be — and right on time. This moment marked not merely the end of our drive but also the bobolink’s astounding feat of flying over 12,000 miles since we’d last heard his call. Bobolinks, who tend to be seen singly, attested to the braiding of wings and land and sea, to the astonishing rhythm of spring’s abundances, and to the persistent migrations of birds, songs and birders.

The straw-headed bulbul (Pycnonotus zeylanicus) is a large, brown bird with a yellow crown and cheeks, thick white streaks on its breast, and two prominent facial stripes. It’s best known for its bubbling, lyrical song.

The straw-headed bulbul (Pycnonotus zeylanicus) is a large, brown bird with a yellow crown and cheeks, thick white streaks on its breast, and two prominent facial stripes. It’s best known for its bubbling, lyrical song.