As the global race for rare earth metals accelerates, industries and policymakers in the European Union and Sweden have increasingly set their sights on the mineral-rich lands of northern Sweden. But amid calls for new mines to fuel a wide range of technologies, a vital truth is being sidelined: There’s a more sustainable and just alternative — urban mining (or circular mining). Recycling metals from existing products and waste can help meet strategic needs without sacrificing the environment or Indigenous rights.

Modern economies are built on a linear model of consumption: Extract, consume, discard. This model underpins traditional mining as well. State-owned mining company LKAB is now planning a new mine in the Per Geijer area of Kiruna, Sweden, a region known to contain significant rare earth element deposits. These materials are crucial for electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, drones, military applications, consumer electronics, and artificial intelligence hardware. The scramble for these materials is partly about climate policy, but also about geopolitics and economic dominance.

But there is a high risk that this industrial expansion will once again harm the Indigenous Sámi population and the ecosystems some of the Sámi depend on. After years of reporting on Sweden’s environmental controversies, one thing is clear to me: Sámi culture is repeatedly steamrolled, and the ecosystems that sustain us are treated as expendable.

People speaking on behalf of the Gabna Sámi village warn that a mine in the Per Geijer area would destroy the last viable migration corridor for reindeer in the region. Reindeer herding is not only an economic activity but a vital part of some Sámi’s culture and identity. Currently, the herds are already squeezed between regulated rivers, expanding urban areas, and existing mining operations. The loss of this last narrow corridor could mark the end of reindeer herding in the area. Some Sámi wonder: Will it even be possible to continue this way of life?

This is not an isolated conflict. In Gállok, outside Jokkmokk, another mining project threatens lands adjacent to the Laponia World Heritage Site. A 2024 review by UNESCO concluded that mining could cause “significant damage” to this protected area, not least because it could threaten the ongoing practice of Sámi reindeer herding in the region.

UNESCO’s criticism was clear: Sweden has failed to adequately consider the site’s cultural and Indigenous value in its decision-making.

Should the growing demand for rare earths be satisfied through industrial expansion that devalues Indigenous rights? Or is there a path that is both sustainable and just? This is why urban mining matters.

Every year the world produces over 62 million metric tons of electronic waste, according to the Global E-Waste Monitor. This includes old smartphones, laptops, solar panels, and batteries. Many of these products contain rare and valuable metals. Instead of discarding them or shipping the waste to low-income countries, these growing resources can be harnessed.

According to the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, recycling cobalt from lithium-ion batteries alone could cover up to 42% of the EU’s cobalt demand by 2050. Extraction from used batteries is far more efficient and environmentally friendly than mining virgin ore. For example, producing 1 kilogram of cobalt from the ground consumes 250 kg of water and generates at least 100 kg of waste. Recycling that same cobalt from batteries requires only 100 kg of water, with far less environmental impact.

Urban mining also helps the EU reduce its heavy reliance on imports. Today China controls about 70% of the global battery value chain and is expected to maintain over 75% of the global material recovery capacity by 2030. Meanwhile the EU’s own recycling infrastructure is underdeveloped, handling only around 5% of the global recovery capacity. A significant portion of the EU’s battery waste is still being exported — ironically, often to the very countries that dominate raw material production — because recycling is considered more cost-effective in the same facilities where those primary materials were originally processed.

Despite local opposition, the Per Geijer project was classified in April 2025 as a strategic project under the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act. Exploration continues. At the same time, the EU has set ambitious recycling targets. By 2031 80% of lithium and 98% of cobalt in batteries must be recovered. Member states are expected to build up domestic capacity and implement laws that drive collection, sorting, and product design for recyclability.

Sweden has the potential to play a role in this shift. A report from the Geological Survey of Sweden and the Swedish EPA found that Swedish mining waste contains up to 500,000 metric tons of rare earth elements, along with significant quantities of cobalt, bismuth, and other strategic metals. But despite this, recycling efforts are hampered by weak policy incentives, legal uncertainty, and underinvestment.

Although Sweden’s Parliament has signaled support for urban mining and the government has launched a circular economy roadmap, new mining continues to take precedence in practice.

This is not inevitable.

Reconciling Indigenous rights with the demand for strategic resources is possible — but it requires a fundamental shift in how northern Sweden is viewed. This is not an empty wasteland where resources can be mined; it’s a living, cultural landscape with its own inherent value and rights. Society’s demand for rare earth metals must not come at the expense of Sámi land. Consumption habits can be adapted, and product designs and recycling systems can be altered.

In Sweden public opinion supports recycling — 8 in 10 Swedes believe it’s important to recycle electronics. Yet 6 in 10 have never recycled an old phone. Worse, much of Sweden’s e-waste is exported to countries with poor labor and environmental standards.

Urban mining is no silver bullet. Some primary extraction will likely remain necessary in the foreseeable future. But it’s a critical piece of the sustainability puzzle. By integrating urban mining into our resource strategies, it is possible to reduce pressure on ecosystems, improve supply chain resilience, boost recycling industries and innovation, and cut dependence on overseas mines — many of which are devastating for women, children, Indigenous communities, and local environments. Most importantly, urban mining offers a path forward where we no longer pit nature and cultural heritage against the technical needs of the green transition and society at large.

There’s plenty of room for improvements, and those improvements should be based on EU law (like the Critical Raw Materials Act and the Batteries Regulation), Sweden’s own circular economy roadmap, international Indigenous rights frameworks, and analyses by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre and Swedish Geological Survey. In other words, they should be logical extensions of existing research, legal commitments, and policy gaps. Sweden’s government and regulatory authorities should:

-

- Implement a moratorium on new mining in Sámi territory until urban mining is fully investigated and developed.

- Develop a national strategy for metal recycling, including mapping of secondary resources, enforceable design requirements, and improved collection infrastructure.

- Ban the export of recyclable battery waste outside the EU to retain critical materials within the region.

- Meet EU recycling targets and invest in Sweden’s own recovery capacity.

Sweden must show that it takes both Indigenous rights and environmental responsibility seriously. Urban mining works, and the time for it is now.

Previously in The Revelator:

On the Horizon: Nature’s Top Emerging Threats and Opportunities

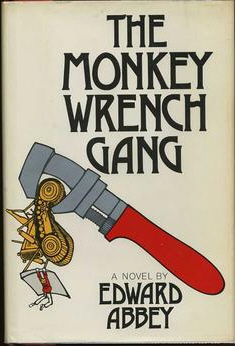

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the first press run of Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, the novel that launched environmental activism and eventually sold more than a million copies.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the first press run of Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, the novel that launched environmental activism and eventually sold more than a million copies.