Washington state is on the cusp of making its biggest climate pollution decision in years. The state has the power to stop the world’s largest fracked gas-to-methanol refinery, proposed along the Columbia River’s shores in Kalama. But a dangerous new climate theory stands in the way: the displacement theory.

If built this single refinery would use more fracked gas than all the power plants in Washington combined and increase the state’s greenhouse gas emissions by between 4.17 and 5.41 million metric tons a year.

Yet project-backer Northwest Innovation Works suggests that building this new methanol refinery is somehow good for our climate.

How is that possible? The company’s rationale is based on the “displacement theory,” which posits that global emissions will increase more slowly if Washington approves the Kalama methanol refinery because the company would ship the methanol to China to make plastics or to burn as fuel. And if Washington-produced methanol doesn’t exist, China will produce methanol using coal-fired power instead of fracked gas.

This twisted logic isn’t just the company’s rhetoric; it’s been repeated in a new draft study by consultants hired by the Washington Department of Ecology, which is now weighing whether to permit the refinery.

The department’s analysis rests on the assumptions that no cleaner methanol or substitutes will attempt to enter the market in the next 40 years and neither the United States nor China will enact new regulations to curtail greenhouse gas emissions. This presents a dim view of humanity’s history of innovation and commitment to tackling the climate crisis.

Any fossil fuel developer can fabricate worse alternatives. And it’s been tried before.

Backers of the Millennium coal-export terminal in Longview, Washington, claimed their coal would displace dirtier coal in Asia. Tesoro claimed its “lower-carbon Bakken crude” would displace dirtier oil when it proposed the nation’s largest oil-by-rail terminal along the Columbia River.

Washington leaders didn’t take the bait on those proposals because displacement is speculative and unenforceable. And, most importantly, our climate can’t afford to lock in fossil fuel infrastructure for the next 50 years. If Washington — or any other state — adopts the displacement theory, it would create a precedent that invites new fossil fuel projects — and more fracking.

The project, however, was dealt a significant blow Nov. 23 when a court sided with Columbia Riverkeeper and our allies (including the Center for Biological Diversity, publishers of The Revelator) by overturning federal permits for the refinery’s dock. The court held that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers cannot reissue the permits without first completing a full “environmental impact statement” to consider the proposal’s life-cycle greenhouse gas pollution and other issues.

While this is good news, we don’t need to wait for a federal agency’s environmental review and decision. Washington can stop this climate disaster in its tracks before the end of 2020.

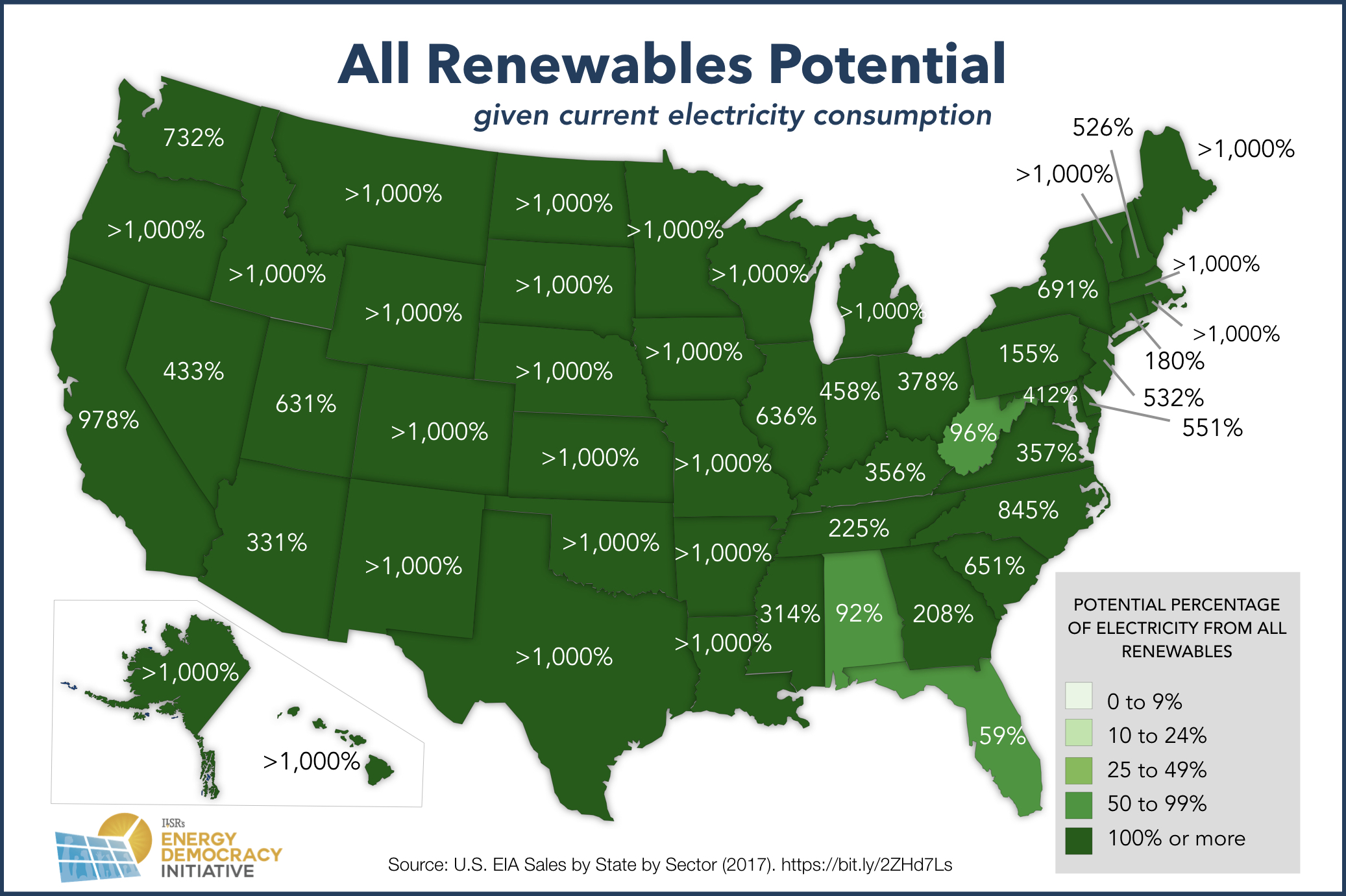

The first step: Washington — a state with a mandate to achieve 100% carbon-free electricity by 2045 — should reject the displacement theory’s bleak and dangerous reasoning.

Research has shown that using hydraulically fracturing to produce shale gas has led to a global spike in methane emissions — a potent greenhouse gas — as well as other environmental harms and health concerns.

In fact, in spring 2019 Gov. Jay Inslee said, “I cannot in good conscience support … a methanol production facility in Kalama.”

If that’s the case, why would Washington adopt the displacement theory, which would ramp up fracking and climate emissions?

The Department of Ecology’s analysis also presents a false choice: Is fuel better if it’s derived from gas or coal? The real comparison isn’t coal versus gas, but fracked gas versus clean energy.

Many climate experts tout vehicle electrification as a necessary step toward a truly low-carbon future, but an abundance of cheap fossil fuels — like Northwest Innovation Works’ methanol — could disrupt the adoption of electric vehicle technology.

The displacement theory is antithetical to everything our state is working to accomplish.

Washington, like many states, is innovating new technologies and fighting for new policies. We’re creating positive change, not passively accepting a dark future.

The Department of Ecology’s initial willingness to accept Northwest Innovation Works’ speculative, self-serving and defeatist climate rationalizations jeopardizes Gov. Inslee’s credibility and accomplishments as a climate leader.

But the story is not over.

The department still has time to abandon the displacement theory. It will issue a final environmental review any day, and based on that review will approve or deny a key permit before the end of the year. If Ecology denies the permit, Northwest Innovation Works can’t build the refinery.

With the climate crisis bearing down on us, we demand Gov. Inslee and the Department of Ecology reject the fossil fuel industry’s false choice and embrace a clean energy future.

The answer is clear: Deny the world’s largest fracked gas-to-methanol refinery. In doing so, Washington will set important precedent that other states threatened by fossil fuel infrastructure can look to when making similar decisions.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

![]()