Over the course of my career, I’ve come down with an endless variety of tropical diseases: leishmaniasis, amoebic dysentery, dengue, schistosomiasis, leptospirosis, countless bouts of diarrhea of unknown origin, dozens of cases of food poisoning, numerous secondary infections, pinworm, wandering hookworm, and dozens of botflies in various parts of my body.

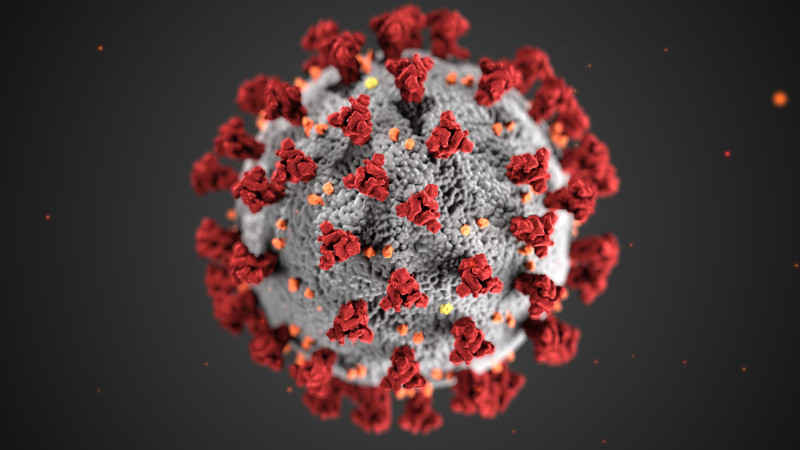

This, plus my interest in new and reemerging diseases (like Monkey-B virus, Ebola, HIV/AIDs, Dengue, Chikungunya and Zika, as well as SARS and MERS — both of which are coronaviruses), led to an idea I’ve been mulling over for more than 30 years, which seems to be playing out now with the novel coronavirus COVID-19.

I call it the “human meat-market hypothesis.”

Superabundance Makes Us Easy Prey for Parasites

If you look at the course of evolution, you see that certain species become abundant, or even superabundant, for whatever reason. Along with this success, you see the accompanying evolution of predators to take advantage of this food resource, this mass of protoplasm, this “meat market” of living creatures. These include the emergence of a wide variety of parasites — viruses, bacteria, protozoans or rickettsia — that make use of these superabundant species. Predators and parasites evolve to depend on these superabundant species for their survival.

One of the world’s more successful, abundant species? Humans. That makes us a huge source of food for potential predators and parasites — a human monoculture, or a “human meat market.”

Saber-toothed tigers and cave bears were a problem for us in the past, and some animals still eat us from time to time. But it’s unlikely that new megafauna predators are going to emerge at this point, leaving certain microfaunal parasites as our major adversaries in the future — and right now.

The more simplified and less diverse ecological systems become, due to our exploitation of those ecosystems, the more we’ll become targets of these emerging pests, unbuffered by the vast array of other species a healthier ecosystem provides.

The consumption of wild animals (aka “bushmeat”) in China, Southeast Asia, West and Central Africa and elsewhere provides a direct human connection to pathogens that would otherwise be restricted to different species living in their natural habitats. Anyone who has ever visited the dreadful markets where bushmeat is sold knows how unsanitary they are and how easily they can cause direct infections to human consumers — which is how the most recent coronavirus jumped to us. The only surprise is that these kinds of outbreaks have not happened more frequently.

Our domestic animals are an even bigger “meat market” for parasites. Domestic mammals account for 60% of all mammalian biomass on Earth, compared to 34% for humans and only 4% for all wild mammals. No wonder we feel we have to pump domestic animals full of antibiotics to avoid the occasional outbreaks of domestic disease epidemics such as mad cow, swine flu, foot-and-mouth disease and avian influenza, which then often spill over into humans.

The combination of the two, the human meat market and our own domestic-animal meat market, is proving deadly.

What does this mean for conservation? Three major steps need to be taken.

Protect Biodiversity

First, we need to protect the full range of biodiversity on our planet, since diverse, healthy and functioning ecosystems protect us. We don’t want our Earth to become less diverse, with people (and our domestic animals) becoming increasingly easy targets for the harmful viruses, bacteria, protozoans and other parasites that will certainly discover that we’re the best, most readily available source of meat.

Stop the Wildlife Trade

Second, we must stop removing wild animals from their natural habitats for human use and consumption, practices that put us into direct contact with their parasites. We strongly encourage countries that are actively engaged in the commercial trade of terrestrial wild animals for food, medicines and pets to ban these practices permanently.

China has already done so in response to COVID-19, but how long will such a ban last? The country also banned bushmeat after the SARS outbreak in 2003, but the markets opened again shortly after the threat passed — and now we have COVID-19. Vietnam’s government is also preparing a directive to stop its $18 billion wildlife-trade market. African countries should also ban commercial bushmeat consumption. Some have made feeble attempts to do so, but most haven’t stuck. These bans need to be strictly enforced, including by focusing on the vast illegal underground markets.

Eat Less Meat

Third, as a society we need to move away from large-scale meat consumption in general and transition to plant-based diets.

Coronavirus has given us yet another wake-up call. We can’t yet determine how severe this outbreak will be, but it should help us prepare for the future, not just in Band-Aid approaches like more masks, hand-sanitizers and test kits, but in attacking the underlying causes of these outbreaks to prevent them in the future. We simply must put an end to the commercial trade in wild animals for food, medicine and pets — for the health of our planet and for us humans who live on it but continue to destroy it with such callousness and ignorance.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

![]()

1 thought on “Coronaviruses and the Human Meat Market”

Comments are closed.