“That which has been damaged can be healed.”

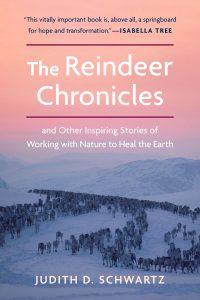

It’s a quote from ecological design pioneer John Todd that opens The Reindeer Chronicles, a new book from author Judith D. Schwartz.

It’s a fitting quote for a time when we’re facing multiple crises and good news is in short supply — and an apt beginning for a book that takes readers across the world to learn about the ways nature’s being harnessed to help restore some of the most damaged parts of our planet.

With stops in Spain, Saudi Arabia, Hawaii, New Mexico and Norway (that’s where the reindeer come in), Schwartz writes about landscape-scale environmental-restoration projects and the restoration of community that often goes along with them.

It’s work that she calls the “inverse of apathy and an antidote to despair.” And it’s work in which we can all participate.

“We’ve been trained to believe that finding solutions is a job for the experts,” she writes. “But many unsung eco-restorers are doing the work, often drawing inspiration from clever creatures like ants, butterflies and dung beetles.”

Writing about the power of nature to heal isn’t new to Schwartz, who’s also written books on the importance of water and soil restoration. But her latest endeavor takes more of a big-picture approach — and offers a dose of inspiration.

We spoke to her about what she learned from looking at large-scale restoration projects and how to put best practices to work in any place.

Why did you decide to write a book about landscape-scale restoration?

Often environmental inquiries get focused on one component, whether it’s carbon or water, and I just felt that there was much to be said about the whole picture. Many of the problems that we look at from a narrower lens can be dealt with through the synergies that happen when we restore an entire ecosystem.

When we talk about climate, one thing that has been missing is the role of functioning ecosystems in climate regulation. And that to me is a huge gap, because a healthy landscape regulates climate via the water cycle and via land-plant-animal-soil dynamics.

I was also really compelled by the work of [filmmaker] John Liu, who I write about in the book. I felt that the restoration he filmed in of the Loess Plateau in China [that helped lift millions out of poverty] was this huge, amazingly successful, large-scale effort that is an inspiration. As he says, once we know that it’s possible to restore large-scale, degraded ecosystems or landscapes, that opens up huge possibilities.

If we can restore ecosystems, then we’ve got solutions that not only will help us address climate change but also deal with food security, water security, human health, and war and conflict.

When you think about regeneration or restoration of land, what does that look like and how is success measured?

I think of it in terms of function. Is this land functioning? How are the carbon, water, energy and nutrient cycles? Are they functioning or have they been distorted?

Land degradation, biodiversity loss and loss of climate regulation can be restored by restoring these cycles. And they work together. In restoring the carbon cycle you’re also restoring the water cycle, because by returning carbon to biomass and to the soil organic matter and deeper soil strata, you’re also enhancing the land’s capacity to hold water and therefore restoring the water cycle.

To know if it’s working, a lot of people talk about biodiversity. For example, Neal Spackman, whose work in land restoration in the Middle East I write about in the book, says he knew the land was returning when he began seeing ants again. Soil cover — less bare soil — is also a metric that people use, as is the land’s capacity to hold water.

One of the things I was struck by in the book was how many of the stories about land restoration were also stories about human relationships. What kind of overlap of community and ecological restoration did you find?

I think that we have gotten disconnected from how much our landscapes are part of us and how much we respond to the land that we’re in. I remember John Liu saying, “the state of our landscapes is a reflection of the state of our consciousness.” And so I think the act of healing land is in itself healing to humans.

What we do, and have done, to the Earth is reflected in what we’ve done to other people. We see this with colonialism, in terms of erasing Indigenous cultures and a large part of those cultures was the relationship to the land.

And I saw that in very profound ways through the work in this book that in allowing those voices to come to the fore, there’s healing for all. And part of that healing is not trying to impose a vision of how landscapes should be and really listening to the wisdom of people who have a profound and long-lasting relationship with a particular landscape.

The projects that you write about are all over the world, under varying conditions. Are there any common best practices that can guide people wherever they live?

Yes, and again John Liu really boiled it down by explaining that when a landscape is moving in the direction of restoration, it follows three trends: increasing biodiversity, increasing biomass and increasing soil organic matter.

Those concepts can be applied anywhere.

Let’s say someone has a lawn and they have one type of grass that looks like a carpet. Even if you just add clover in there, just adding more diversity, which either will happen on its own or if you have a seed mixture, that’s one positive thing. And the implications of that are that those plants are then bringing different nutrients into the soil. They’re feeding different microbes.

For increased biomass, let’s take the lawn again, you can leave some patches of plants that can become a meadow. Let things grow higher. Add more plants. That’s more biomass.

For soil organic matter, use composting. You can also work to build your soil by making sure you’re not using fertilizers and allowing grasses to grow higher, which means that their roots are going deeper.

There are lots of different ways that you can measure that. I really like a term that my colleague Peter Donovan of the Soil Carbon Coalition talks about, which is the notion of “biological work.”

Another way to think about whether the landscape is on the path towards higher function or restoration is how much biological work is happening. Think of a ray of sun. If that ray strikes the earth, is it hitting asphalt? Is it hitting a monoculture grass where the soil is compacted? Or is it hitting a lot of different leaf surfaces? The more surfaces and the more opportunities that ray of sunshine has to be used in the process of photosynthesis, then the higher the level of function of that land.

Without biological work making use of this energy, if our ray of sunlight hits, say, an asphalt driveway, that becomes heat. That this scenario is being played out across large areas of degraded landscapes and soil sealed over by roads, buildings and parking lots is an important narrative thread within the story of climate change.

What do you hope this book accomplishes?

I guess the first thing is to open up our range of what we think of as possible. We’re told what the problems are, and it’s almost like everything is a fait accompli. But once you know that certain things are possible, or as John Liu says, once you know that we can rehabilitate large-scale damaged ecosystems, that throws everything open.

And it’s not just that restoring landscapes is possible — it’s also happening. This goes from small-scale efforts to extensive initiatives. For example, the AlVelAl/Commonland project is across nearly 2.5 million acres in southern Spain.

There’s also joy in working toward embracing the possibilities and working toward the solutions.

I always tell my friends that the happiest and most fulfilled people I know are those who are working to restore landscapes. Healing the landscape is healing to oneself. And the wonderful thing is that the landscape rewards you really quickly. Our earth systems want to heal.

And once we understand that healing ecosystems is a possibility and will contribute to addressing many of the challenges that we have — well, there’s work to be done. So let’s invite people into that work. It’s not only providing jobs, but it’s also providing meaning, because what can be more valuable and more life-affirming than healing our environments?

![]()