A new year brings with it new opportunities — and more of the same environmental threats from the previous 12 months.

But as we see year after year, many environmental issues tend to fly under the radar. Sure, climate change has started to get wider coverage from some newspapers and TV networks, but a lot of important stories still get missed (or dismissed by partisan outlets). Meanwhile the media devotes precious little space or airtime to stories about endangered species, environmental justice, pollution or sustainability.

Maybe that’s why these issues also get so little attention from legislators or the general public.

We can work to change that. Here are six of the biggest but most likely to be ignored environmental stories that The Revelator expects to follow in 2022.

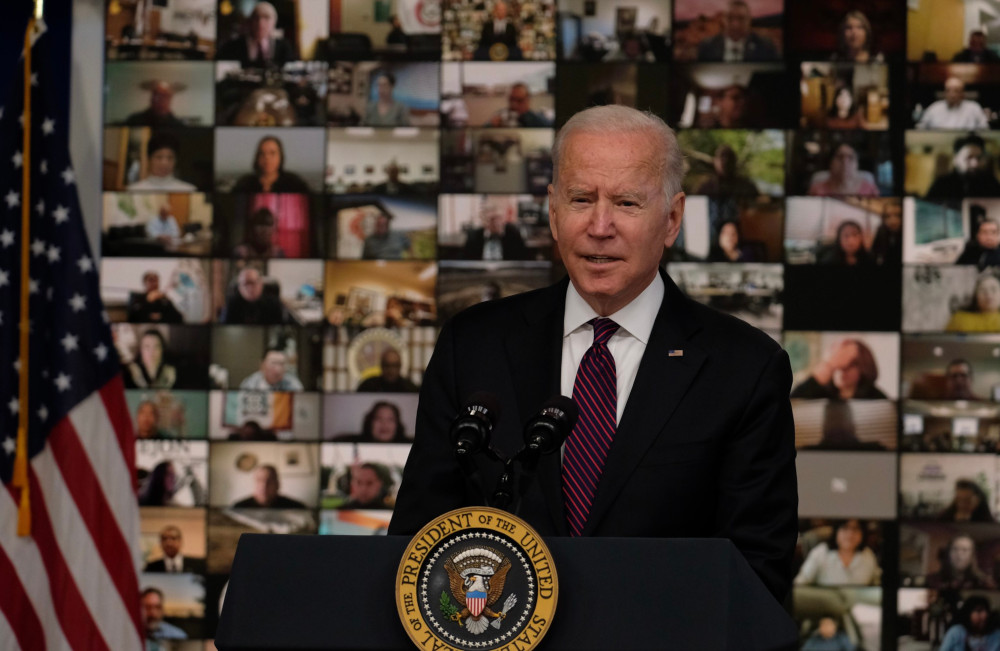

Biden-Watch and the Specter of 2024

Following last year’s difficult election, we proclaimed 2021 the start of “the rebuilding years.”

That has proved somewhat true: Under President Biden, many of the previous administration’s antienvironmental initiatives and deregulatory efforts have fallen like dominoes.

But in other ways, Biden has not lived up to his campaign promises on environmental issues. Most notably, the administration licensed new fossil fuel drilling rights at a breakneck pace in 2021, in stark contrast to the candidate’s promises (and even some of his early symbolic actions, such as his executive order to make the U.S. government carbon-neutral by the year 2050).

Although the Beltway press doesn’t dig into this as often, all eyes should be on Biden’s next environmental moves. Can he deliver on the real threats facing the planet? Or will this administration become yet another failure for climate and biodiversity?

We’re guessing it will be a combination of both, with some clearcut victories in need of amplification and a few partial or flat-out failures.

The real proof in the political pudding will come this November, when the 2022 midterm election could create long-term challenges for the planet. The increasingly authoritarian Republican party is doing everything it can to game both the 2022 and 2024 elections in its favor: voter suppression, redistricting, removing bipartisan election officials, and even passing legislation to allow it to throw out election results the GOP doesn’t like, all while perpetuating the damaging Big Lie of election fraud to discredit the entire process.

The media, other legislators, activists and voters need to make sure this stays a key component of the stories we tell in the year(s) ahead. Because if Trump or someone like him ascends again to the presidency in 2024, or if the Republicans take over the House in 2022, then it’s one step closer to lights out for the planet.

Biodiversity in Crisis

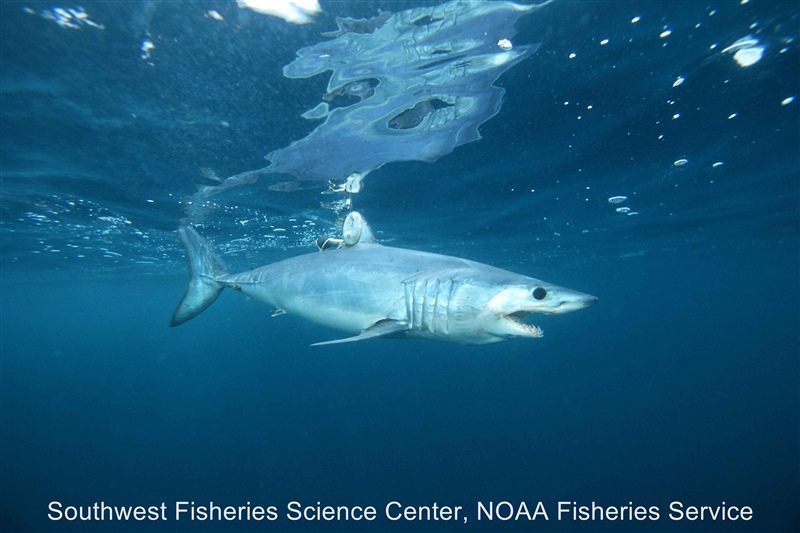

This past year saw several big-picture studies identifying the extinction risk of large groups of species, and the news wasn’t good. One third of shark species, the studies found, are threatened, as are 30% of trees, half of all turtles, 16% of dragonflies and damselflies, 30% of European birds and 16% of Australian birds.

And then, of course, there were the extinctions.

Tragically, we don’t expect any of this to slow down in 2022. We’ve already heard from sources about potential extinction declarations that could come in the months ahead, mostly for species that haven’t been seen in several decades.

As usual, few of these get widely covered in the media. We’ll do our best to bring you this news, as well as conservation success stories that tend to get overlooked in our “if it bleeds, it leads” media environment.

The pandemic will also continue to affect the conservation movement, and we need to keep these issues in the public eye. The past two years have seen a lot less on-the-ground research around the world, although some scientists have started to break through the need to stay at home and gotten out into the field.

Will the same thing happen with important international discussions? More than 190 nations are currently scheduled to meet in April to discuss global agreements to protect nature and biodiversity. The arrival of the omicron variant — one more reminder that vaccines still haven’t been equitably distributed around the world — has now put that meeting, and perhaps others like it, in jeopardy.

But life finds a way. Even if we can’t do work in nature or in person, there’s always Zoom. The work that concluded sharks’ extinction risk wouldn’t have been possible without today’s online communication tools. These types of events don’t generate as much media attention, but they will generate stories worth telling if we’re open to listening.

A Plastic Mess

Will this be the year the United States finally hears the message about the dangers of plastic pollution?

Let’s hope so, because a new report from the National Academy of Sciences, published in December, revealed that the United States is a top contributor to the problem. According to the report, U.S. residents generated more plastic waste in 2016 than any other country — a staggering 42 million metric tons. That’s more than all the European Union and twice that of China.

The report, which was mandated by Congress, recommends the United States develop a comprehensive policy to reduce plastic waste in the environment. Of course legislators could get a jump on that if Congress passed the Break Free From Plastic Act introduced last March.

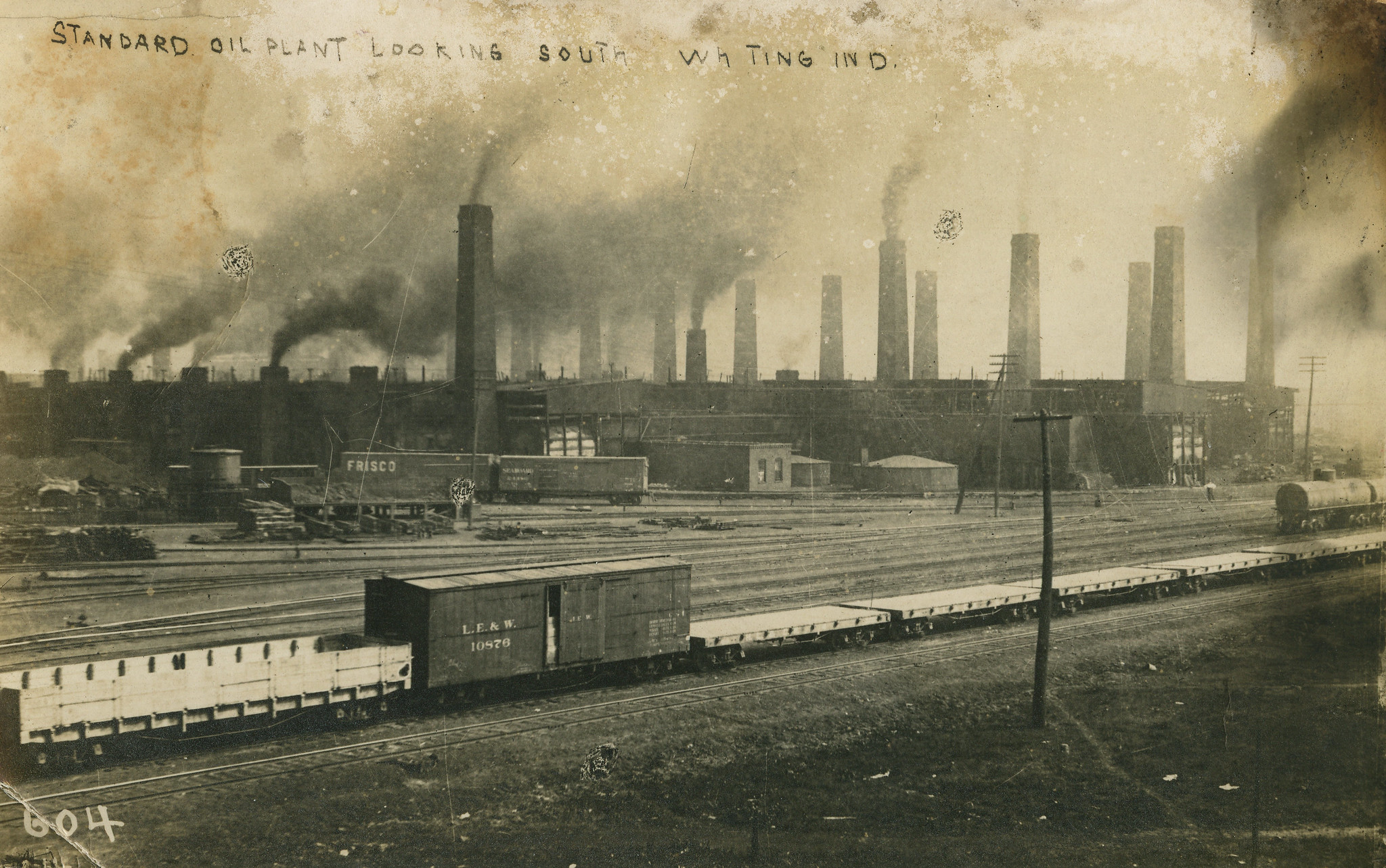

And there’s another strategy, too — turning off the tap on plastic production by halting the extraction of fossil fuels that provide plastic feedstocks and stopping the build out of massive new petrochemical facilities. The Army Corps of Engineers is in the midst of an environmental review of one such project now — a $9 billion project by Formosa Plastics in St. James Parish, Louisiana. That could set the stage for a lot of future progress.

No matter what happens, the focus needs to remain on this issue, which not only poisons communities but exacerbates the climate crisis. It’s time for leadership, not just in this country, but around the world.

Expect Extremes

There should be nothing surprising anymore about the fact that we’re in for a wild weather ride every year now, as climate change turns up the heat and supercharges many storms and wildfires.

From 1980-2020 the United States had on average about seven weather and climate events that topped $1 billion each. But from 2016-2020 that average has shot up to 16.

Researchers are increasingly able to show the fingerprints of climate change on specific weather events. A Climate Brief investigation into the field of “extreme event attribution,” pioneered by scientists at World Weather Attribution, showed that climate change made 70% of 405 extreme weather events either more likely or more severe. The media needs to make this connection more often.

So, we know it’s coming. Now what will we do about it? Expect to see more stories about climate change resilience and how states will spend the $50 billion earmarked to protect against droughts, heat and floods in the new infrastructure bill. And hopefully we’ll see ample coverage of how this money gets to the communities that need it the most.

Doing Renewables Right

We’re off and running — or at least jogging — on the race to decarbonize. Initial projections show that in 2022 the United States could see a record amount of new wind energy (27 gigawatts) coming online, as well as twice as much utility-scale solar (44 gigawatts) compared to last year, and six times as much energy storage (8 gigawatts).

Meanwhile 28% of U.S. coal plants are projected to close by 2035.

But don’t hold on too tightly to those projections for renewables. Rising costs and supply-chain problems could slow or halt some planned projects. On the other hand, renewables could get a big boost if Congress manages to passes the Build Back Better bill.

Ramping renewables will come with a few other challenges, too, that we should keep our eyes on: Can raw materials like lithium and cobalt be sourced without endangering human rights or terrestrial and marine ecosystems? Can projects be sited and managed in ways that don’t exacerbate biodiversity concerns? Can we ensure that poor communities and communities of color that have borne the brunt of the fossil fuel economy be the first beneficiaries in the energy transition and leaders in the process? These are the types of tough questions everyone should start asking as we make this vitally important transition.

Getting Direct

Even amidst the pandemic, dedicated environmental activists refused to let their voices be silenced.

We’ve seen a dramatic rise in direct action over the past few months, with climate protestors temporarily disrupting Australia’s largest coal port by scaling and then suspending themselves from massive machinery, going on a very public 14-day hunger strike, defending a sacred waterway in British Columbia, protesting for voting rights and a whole lot more.

And they’re just warming up. The Extinction Rebellion climate protest group has promised a return to direct action now that vaccination rates have increased — indeed, they’ve been quite active the past few weeks.

The protests and disruptions reflect societal anger at corporate and government resistance to reform. They present the world with dramatic images and powerful messages, many of which get otherwise ignored by the media and legislatures. These events might not achieve much individually, but collectively, given time, they work.

That’s also why such activism is so risky. Last month Chilean activist Javiera Rojas was murdered, the latest in an ever-increasing string of deaths and other violent attacks committed against environmental defenders around the world.

These are the stories we all need to watch — and the messages we should never forget.

Previously in The Revelator:

![]()

This article is published as part of

This article is published as part of