Forget clothes made out of recycled plastic. Forget beach cleanups. These are just distractions, says Shilpi Chhotray. She’s the founder of the new podcast People Over Plastic, a BIPOC storytelling collective that’s taking on plastics, climate change, and racial and gender justice — one episode at a time.

To Chhotray, the real solutions to halting the plastic crisis come from stopping the production of plastics and the fossil fuels needed to make them. And from scaling zero-waste supply chains, businesses and cities. And from addressing the harms done to communities of color that have borne the brunt of plastic pollution for decades — both in the United States and abroad.

Want to know more? Chhotray hopes so. After years of working as an activist and communications leader on plastics issues, she founded the podcast to focus on how we can work together to address the crisis.

Each episode, around 30 minutes, features two guests — usually one from the United States and another from either Asia, Africa or Latin America. It’s a balance of stories about innovation, art, and activism — all pointing toward solutions, all told by BIPOC voices — with a goal of taking the conversation about plastics well beyond traditional environmental circles.

The Revelator spoke with Chhotray about the power of storytelling, upcoming guests she’s most excited about and who she hopes listens to the podcast.

You’ve been working on plastic issues for a while. How did the idea of this podcast come about?

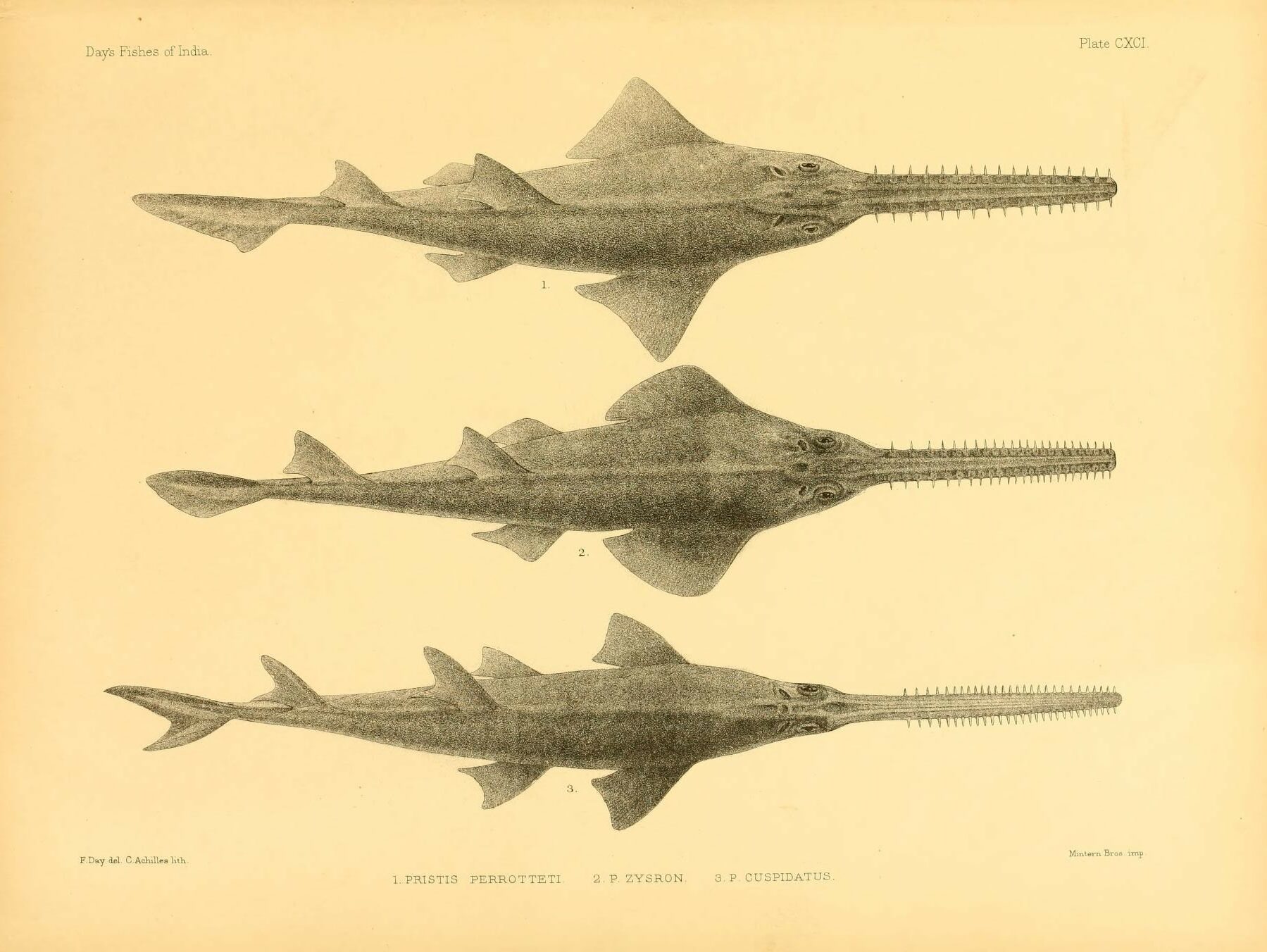

I come from a marine science and conservation policy background. I started looking at microplastics in fish in 2014. Back then it was called marine debris — people weren’t even calling it plastic pollution yet. Over the years I learned that that was just the tip of the iceberg. When I joined Break Free From Plastic in 2017, I got laser-focused on the human side of the issue and the social justice side of it.

I worked at Break Free From Plastic for about four years and I loved every second of it. I was meeting with people all over the world. I was part of very complex and interesting strategy conversations. The missing link, though, was that we were not getting outside the regular environmental circles. When I talked to people outside of our community, they didn’t really know that plastic came from oil. And I was seeing more and more of these influencers and celebrities wearing sports bras made of recycled water bottles. We know that isn’t a real solution, it’s a distraction.

After giving birth to my son, I spent about four months on maternity leave [and] I was really able to step back and just sort of marinate on what I was seeing from the outside. I decided I wanted to get even more honed in on the storytelling side of things and getting into circles that weren’t talking about the intersectional issues of plastic, which are so important.

So that’s where this idea was born for a storytelling collective led by BIPOC voices. The podcast has three focus areas; climate, innovation, and racial and gender justice. Generally, all of the episodes cover these three pillars.

There’s a lot of press about the threat to ocean life from plastics. Tell me about the coverage gap you’re trying to close by focusing on BIPOC communities that are also in harm’s way.

By focusing on just the ocean, you’re putting the accountability on the end of the lifecycle, which means consumers. It’s a very easy way for corporations to divert attention from their role in the crisis.

The other thing that misses is that it’s communities of color all over the world — from the Gulf South in the United States to Manila, Philippines — who are the most impacted in very brutal ways by the entire plastic pollution lifecycle. We’re not just talking about a little bit of trash in the community. They’re drowning in it.

And oftentimes it’s trash from another part of the world. The United States is outsourcing about 60% of our waste. When you talk to recycling centers, they’ll say they’re sending it to foreign markets. These “foreign markets” are often the backyards of my friends.

I’ve visited a lot of these communities and they have some of the brightest minds working on this issue. But unfortunately, their voices aren’t always the ones making headlines.

I think with all of the racial justice uprisings with George Floyd, with Black Lives Matter, with youth activists, there’s a moment right now where we need to pivot on plastics — and environmental issues in general — and really give the social justice piece the justice it deserves.

The most powerful way to do that is to set up systems so that people can tell their own stories.

The very first interview in your podcast is with artist Von Wong. What kind of power do you think art has to move the needle on this issue?

Art is this incredible way to pull people in by not saying anything at all. And I’m a very wordy individual — I’m a communicator. But I wanted to have this first episode present itself as discovery-to-frontline. And what I mean by that is art can be a way to discover an issue, whether you’re deep in the weeds of it like me or are someone who has decided to skip the straw during lunch — who might not know all the issues but knows this isn’t good for the planet.

So this is a way to pull people in from all walks of life with different backgrounds on plastics and intersectionality. Von Wong’s work is really, really exciting. It’s almost fantasy-like, and he uses plastic in a way that you can’t look away from it.

I built a 3 story tall giant faucet with plastics flowing out of it to invite the world to #TurnOffThePlasticTap

Check it out -> https://t.co/3PUXWTY4tJ pic.twitter.com/KRgJAcQKMm

— Von Wong (@thevonwong) October 5, 2021

He’s a long-time friend of mine and when he started telling me about his Turnoff the Plastic Tap project, which was featured in episode one, I was really interested in the oil piece. So it’s not just turning off the tap on the brands and the corporations, let’s also turn the tap off on the industry that’s producing it, which is fossil fuels.

That was a really important hook for us to start with and then go to Miss Sharon [Lavigne], who is on the frontlines of the fossil fuels and petrochemicals side of things [in St. James Parish, Louisiana].

What are some of the other stories you’re featuring?

One of the people I interview in episode three is the great-grandson of the famous dabbawalas network in India. It’s a 130-year-old system. These gents get on a bike and they deliver a hot lunch to people at work every day in a [metal lunchbox]. It’s not a catering service, though — they go to the house of the person at work, pick up the lunch from whoever’s cooking it, and then they bike with it over to the place of work to deliver the hot lunch. There’s no plastic in this system. There’s no emissions because they’re on bikes. In Mumbai they deliver around 200,000 lunches a day.

I also talked to Zuleyka Strasner, who’s an incredible entrepreneur. She also has a very interesting background being Black and trans and competing for money with Silicon Valley 22-year-old Stanford tech kids. She founded Zero Grocery, which is scaling the supply chain to be as efficient as Amazon, but completely plastic free.

These are the kinds of people I’m interested in. Yes, they are people of color. Yes, they have inspiring lived experiences. But they’re also wicked smart and they’re scaling these systems that could be replicated in every city in the world. That’s what’s going to move the needle.

It’s not whether I have my Klean Kanteen [reusable bottle] today. That’s not enough anymore and we need to get that message across. And that goes for policies to ban the bag. Great, ban the bag. Ban the straw. We need an overhaul of all the problematic single-use items and then also stop the petrochemical industry from growing. And we do that through the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act, which is in Congress right now.

We’re really trying to drive home the message to decisionmakers that who is at the table matters tremendously. BIPOC people are impacted by this issue the most. We need to be not only inviting them to the table but creating the space for them to create the table as well. That’s actually what episode two is about. It’s called “If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.”

Knowing that personal responsibility isn’t enough, what should people do to try and affect the system-level changes we need?

That’s such a good question. I want to meet people where they’re at. That’s why I created this podcast, because not everyone has the bandwidth to call their senator, do a letter-writing campaign or show up at Starbucks to protest. After I became a mom, it really changed my mindset and got me thinking about what people can do on their morning commute, when they’re in the shower, when they’re at the dinner table. Could they listen for 30 minutes to these stories? Then, if they feel compelled, take that next step and learn about a policy or a brand audit or how to force corporations to be more accountable.

One of the easiest things people can do is tweet. If you can tweet a story and tag a brand and be like, “Hey, I like your product, but I hate your packaging. Do something about it.” It shouldn’t be on the consumer. These multibillion-dollar corporations have multibillion-dollar budgets, and they need to innovate.

That’s really my ask: Can you use the platforms that are at your fingertips to make some noise?

One of my friends told me that she was shook after hearing Miss Sharon’s story. She happens to have 95,000 followers on Instagram. If she puts out that one story, that in my mind is its own campaign tool.

For us, we’re asking people to listen and have a chat with your kids at dinner, or if you’re the kid, have a chat with your parents over lunch. I think there’s something really powerful about learning stories.

I would like everybody to listen to this podcast, which is probably not the smartest [goal] because everyone’s like, “you need to figure out your target audience.” But you know, my target audience is honestly the planet.

There’s so much power in these stories that wherever you are in society — whether you’re a fifth grader or you are somebody that’s a policymaker — there’s a way for you to plug in.

Previously in The Revelator:

Plastic Pollution: Could We Have Solved the Problem Nearly 50 Years Ago?

![]()