We’re running out of time to get things right.

With the final installment in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 6th Assessment Report released this week, the world’s leading climate scientists have offered a stark warning that we need to cut our greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030 or face a “rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for al l.”

l.”

This will require an abrupt about-face as emissions continue to rise despite the massive body of scientific literature affirming the dire risks of proceeding with business as usual.

“Recognize that you are living through the most profound moment in human history,” climate scientist Joëlle Gergis tells The Revelator. “How bad we let things get is still in our hands. Averting planetary disaster is up to the people alive right now.”

The Australian scientist is one of the lead authors of the latest IPCC assessment. She has also issued a rising call to action in a new book, Humanity’s Moment: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope.

It’s clear from the book that Gergis isn’t a shout-it-from-the-rooftops kind of person. But she felt compelled to share the loss she was feeling — not just as a scientist but as a person. And it’s something she hopes more scientists will do.

“It’s a long-held myth that a credible scientist should be devoid of human emotion, presenting our work rationally, without commentary,” she writes. “Given that humanity is now facing an existential threat of planetary proportions, and scientists are the people who really know exactly what’s at stake, shouldn’t that logically include acknowledging our sense of despair, anger, grief and frustration?”

Humanity’s Moment provides a front-row view of our planetary emergency. Not surprisingly, it’s scary. Gergis writes:

The more I hear, the more I realize that the situation is far worse than most people can imagine. In truth, it’s also hard for me to fathom that our generation is likely to witness the destabilization of the Earth’s climate; that we will be the last to see the world as it is today.

That’s what really keeps me up at night. I wonder if we may have already pushed the planetary system too far, unleashing a cascade of irreversible changes that have built such momentum we can now only watch as they unfold.

For those who need a refresher on how we got to this perilous moment, the book summarizes the science of climate change and explains concepts like the importance of polar areas in regulating the Earth’s climate, the threats to biodiversity, the human health risks, the cultural losses to come, and why the scientific community has been stunned by the rate of change they’re seeing.

But it’s also deeply personal. Gergis writes about her fear that we will not be able to right this ship. And what it means to live with the weight of that.

“It’s a pretty fraught moment, to be honest,” she tells The Revelator. “As a scientist trying to sound the alarm, I feel a sense of responsibility to do what I can to help people understand the significance of the time we are living in. I don’t think most people are aware of how bad things are, or that we can still do something to avert the worst aspects of climate change.”

And that last part is key. All is not lost … yet.

But we do need to take swift and meaningful action. The good news is that we have a roadmap to follow.

“The IPCC has very clearly laid out a path toward stabilizing the Earth’s climate. We know exactly what we need to do, we just need governments all over the world to urgently implement policy to avert disaster,” she says. “For that to happen we need ordinary citizens to vote for politicians who will take real leadership, and also be prepared to do whatever we can in our own lives to live more sustainably on the planet.”

Of course the gist of this action requires leaving fossil fuels in the ground, something major governments of the world — most especially the United States — have thus far failed to do. And the approval last week of a large new oil-drilling project in Alaska shows there’s still a long way to go.

But Gergis also highlights other bright lights, including regionally led renewable energy transitions, and a shifting tide of public sentiment and coordinated action. “The social tipping point we need is now clearly on the horizon,” she writes.

And in hand is irrefutable evidence gathered by scientists in the latest IPCC assessment that was compiled over countless hours, distilled from thousands of studies by researchers working to exhaustion. All so we could have the scientific foundation to guide action.

Scientists have done their part. Will we do ours?

“The 2020s will be remembered as the decade that determined the fate of humanity,” says Gergis. “We can each choose to be part of the critical mass that will change the world. And when we do, it will bring profound meaning and purpose to our lives.”

Previously in The Revelator:

Why We Need Environmental Justice at the Heart of Climate Action

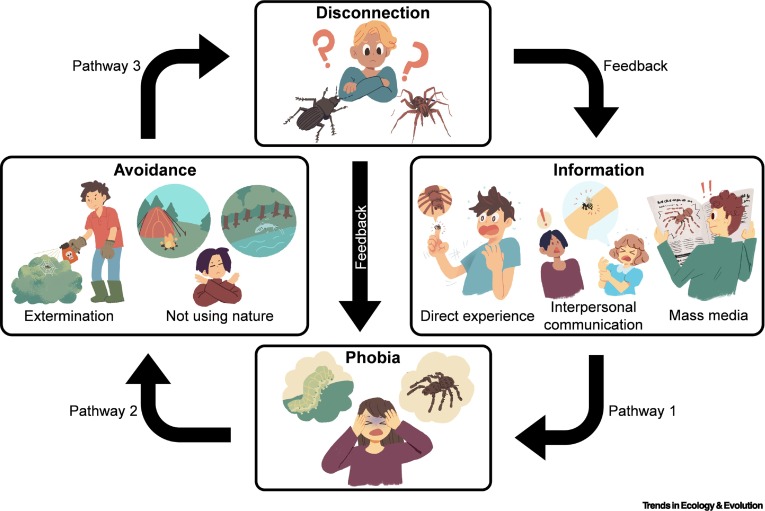

That image, of course, details how biophobia builds into a feedback loop that gets worse at every step.

That image, of course, details how biophobia builds into a feedback loop that gets worse at every step.