Climate change is already shaking up the natural world, changing the timing of seasonal snow melts, flower blooms and animal migrations. Now a new study from researchers at Utah State University suggests that, not surprisingly, it will also change when people interact with those landscapes.

The research, published in Global Environmental Change, projected how the use of state and federal public lands in the United States may change in the next 30 years under two different warming scenarios.

The biggest changes, they found, will come during the summer months. Their research showed that by 2050 it will simply be too hot to have fun outdoors in many places. As a result of these rising temperatures, they predict that outdoor recreation on public lands in the summer will fall 18% under medium emissions projections and 28% under a high emissions scenario.

As for the winter months, when current temperatures tend to keep people away from forests and woodlands, that will change, too. Warmer temperatures will result in more people looking to access public lands — a projected rise of 12-20%.

Springtime will only see a slight bump of 5-9%. They found no significant likely changes in the fall.

Those numbers reflect the United States as a whole, but there were also some significant regional variations. The researchers saw summer use declines in all locations, but the sharpest dip would occur in the South Atlantic-Appalachian region — where things are already hot. Public lands recreation there could fall as much as 79%.

When it comes to winter, the Great Lakes region is likely to see the biggest jump in use, with a 42% increase under the medium warming scenario. The only region expected to see a decline in winter demand is the Upper Colorado Basin, where skiing and other snow sports are a favorite winter pastime that just won’t be possible as often under higher temperatures.

Changing Operations

These changing patterns will come with costs, not just for those planning their annual summer tour of national parks but also for park managers and people living in communities near popular public lands.

“In many locations, land managers may want to consider preparing for an increased peak season length, and more visitors in the winter compared to levels observed in the past,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Managers may need to shift resources to accommodate these changes. A bump in traffic during previously slow “shoulder seasons” could require a change in staffing and maintenance. The corresponding shifts would also have financial implications for the communities surrounding public lands that may see typical summer crowds fall off and more visitors during current off-peak times.

That administrative burden comes on top of the challenges many parks already face. National park visitations jumped 15% in the past decade. At the same time budgets remain flat, and some parks are dealing with staffing shortfalls, the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks reports. Rocky Mountain National Park, for example, saw a 58% increase in visitors between 2010 and 2019, but had 16% fewer employees to handle the rush of tourists.

To deal with crowds, national parks like Glacier and Acadia now charge fees for parking or driving in popular spots. Others, like Yosemite National Park and the Three Sisters Wilderness in Oregon, have instituted an advance reservation permit system to limit use.

A drop in summer visits could help ease some of this strain, but warming temperatures will trigger other changes to public lands and bring different concerns.

An Incomplete Picture

In the Global Environmental Change study, researchers noted that they didn’t take into account any indirect changes from rising temperatures. In addition to the heat, climate change could remove many of the qualities people currently admire about our public lands — or make them more inhospitable.

For example, people may not want to plan their recreational activities in parks “with melted glaciers or in places that recently experienced wildfire.”

This isn’t hypothetical. Climate change has already triggered challenges to public lands’ access. In September high-wildlife risk forced California officials to temporarily close all the state’s national forests. And last year, during the height of the tourism season, Yosemite National Park closed because of dangerous air quality from the region’s wildfires. Climate change is increasing the severity of fire risk across the West, and shifting the annual fall foliage season in the northeast.

The National Parks Conservation Association has warned that rising seas, longer droughts, less snow, and more severe storms from climate change also threaten these prized ecosystems.

“Nearly everything we know and love about the parks — their plants and animals, rivers and lakes, glaciers, beaches, historic structures, and more — is already under stress from these changes, which together amount to a state of crisis for our public lands,” the organization reported.

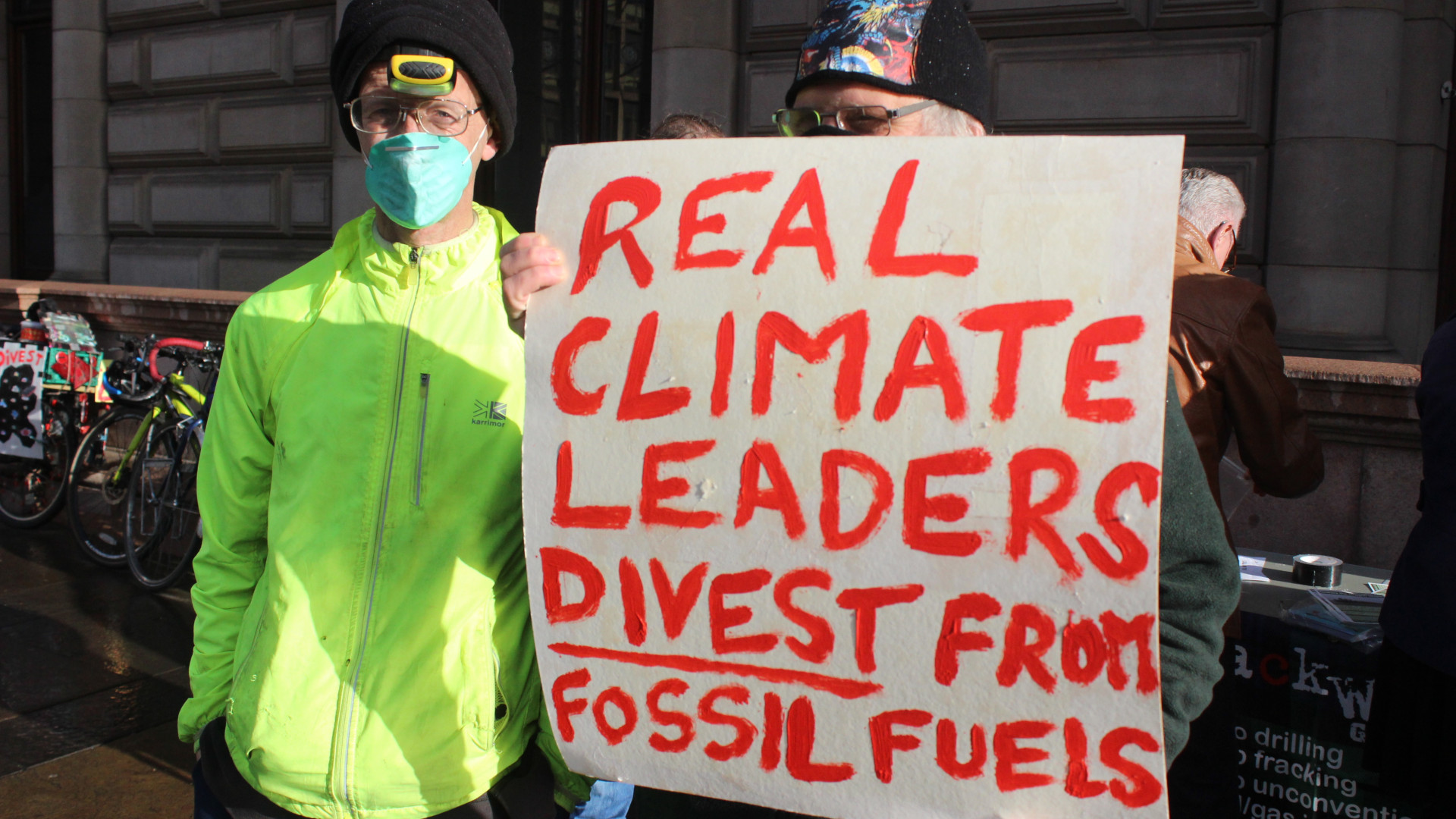

Ironically, while public lands face big threats from climate change, many of those same lands are used for extracting the fossil fuels that drive the crisis. A 2018 report by the U.S. Geological Survey found that emissions from fossil fuel extraction on federal lands amounted to more than one quarter of national emissions. That’s led environmental groups to call for an end to fossil fuel extraction on public lands and for the lands to instead become a climate change solution.

“Given that wildlands on public lands are managed by the federal government, there’s a clear opportunity to ensure they act as carbon sinks and not carbon sources,” the Wilderness Society reported. “Protected wildlands on public lands could maximize the absorption of carbon dioxide and avoid unnecessary release of greenhouse gases that would hinder other efforts to slow down climate change.”

That would be welcome news to all who benefit from public lands — not just humans.

![]()

The recovery kept me out of the mountains for a long time. But finally a grand day came: My partner and I hiked up into the talus slopes of the North Cascades in Washington state. Mount Baker stood before us and Mount Shuksan at our backs — a day of perfect heaven. Suddenly his face lit up: “Hear that? Eeeeep!” I strained my ears to listen and heard nothing. “You don’t hear that?” he cried in dismay. I felt divorced, absented from something that, even when I was far away, had made my world feel whole and alive.

The recovery kept me out of the mountains for a long time. But finally a grand day came: My partner and I hiked up into the talus slopes of the North Cascades in Washington state. Mount Baker stood before us and Mount Shuksan at our backs — a day of perfect heaven. Suddenly his face lit up: “Hear that? Eeeeep!” I strained my ears to listen and heard nothing. “You don’t hear that?” he cried in dismay. I felt divorced, absented from something that, even when I was far away, had made my world feel whole and alive.

These days more and more artists are turning their feelings about climate change, environmental justice and the extinction crisis into powerful creative works. It’s easy to see why. These issues affect just about everybody — a new recent study found that about

These days more and more artists are turning their feelings about climate change, environmental justice and the extinction crisis into powerful creative works. It’s easy to see why. These issues affect just about everybody — a new recent study found that about  Bewilderment

Bewilderment Once There Were Wolves

Once There Were Wolves How Beautiful We Were

How Beautiful We Were Harrow

Harrow Appleseed

Appleseed Rabbit Island

Rabbit Island Canyonlands Carnage

Canyonlands Carnage The Living Sea of Waking Dreams

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams Milk Teeth

Milk Teeth Hummingbird Salamander

Hummingbird Salamander The Hungry Earth

The Hungry Earth