The internal combustion engine had a good run. It helped get us to where we need to go for more than a century, but its days as the centerpiece of the automotive industry are waning.

As countries work to cut greenhouse gas emissions, electrification is stealing the limelight.

While there’s still a long road ahead — electric vehicles only accounted for 3% of global car sales in 2020 — EV growth is finally climbing. From 2010 to 2019 the number of EVs on the road rose from 17,000 to 7.2 million. And that number could jump to 250 million by 2030, according to an estimate from the International Energy Agency.

The growing demand for electric vehicles is good news for limiting climate emissions from the transportation sector, but EVs still come with environmental costs. Of particular concern is the materials needed to make the ever-important batteries, some of which are already projected to be in short supply.

“Climate change is our greatest and most pressing challenge, but there are some perilous pathways to be aware of as we build out the infrastructure that gets us to a new low-carbon paradigm,” says Douglas McCauley, a professor and director of the Benioff Ocean Initiative at the University of California Santa Barbara.

One of those perilous pathways, he says, is mining the seafloor to extract minerals like cobalt and nickel that are widely used for EV batteries. Extraction of these materials has thus far been limited to land, but international regulations for mining the deep seabed far offshore are in development.

“There’s alignment on the need to go as fast as we can with low-carbon infrastructure to beat climate change and electrification will play a big part in that,” he says. “But the idea that we need to mine the oceans in order to do that is, I think, a very false dichotomy.”

Supply and Demand

Tesla may have made owning an EV cool, but a slew of other companies now hope to make it commonplace.

The latest is Volvo, which announced at the beginning of March that it will make only electric cars by 2030. This follows news that Jaguar will be all-electric in 2025 and Volkswagen after 2026. General Motors says it’s aiming to make its cars and light trucks electric by 2035, while Ford is doubling its investments in EVs and plans to sell only electric cars in Europe by 2030.

There are a number of factors that will determine how quickly people adopt the technology — charging infrastructure, battery range, affordability — but top of mind for some is manufacturers’ ability to keep production pace, particularly when it comes to the lithium-ion batteries that are used in not just EVs but other technologies like cell phones and laptops, as well as energy storage for solar and wind.

A 2019 study by the Institute for Sustainable Futures at the University of Technology Sydney found that demand for lithium could exceed supply by next year, which would drive up prices and interest in more lithium mining. Demand for cobalt and nickel, also key battery components, will exceed production in less than a decade.

“Cobalt is the metal of most concern for supply risks as it has highly concentrated production and reserves, and batteries for EVs are expected to be the main end-use of cobalt in only a few years,” the report’s authors found.

Vying for control of these crucial materials has geopolitical implications. Right now, many of the materials are concentrated in a few nations’ hands.

Most of the cobalt used in batteries today is claimed by China from mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where extraction has come with human rights abuses and environmental degradation. Most of the global lithium supply is found in Australia, Chile and Argentina.

Supply-chain issues have also caught the attention of President Joe Biden, who issued an executive order in February directing the secretary of Energy to identify “risks in the supply chain for high-capacity batteries, including electric-vehicle batteries, and policy recommendations to address these risks.”

As pressure mounts to claim terrestrial minerals, commercial interest is growing to extract resources from the deep seabed, where there’s an abundance of metals like copper, cobalt, nickel, manganese, lead and lithium. Investors already expect profits: One deep-sea mining company recently announced a plan to go public after merging with an investment group, creating a corporation with an expected $2.9 billion market value.

But along with that focus comes increased warnings about the damage such extraction could do to ocean health, and whether the sacrifice is even necessary.

The Deep Unknown

The high seas are “areas beyond national jurisdiction,” and mining their depths will be managed by an intergovernmental body called the International Seabed Authority.

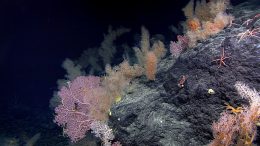

The group has already approved 28 mining contracts covering more than a million square kilometers (360,000 square miles). It’s still drafting the standards and regulations for operations, but when companies get the go-ahead they’ll be after three different mineral-rich targets: potato-sized polymetallic nodules, seafloor massive sulphides and cobalt-rich crusts.

But there’s also concern that we still don’t adequately understand the risks of operating giant underwater tractors along the seafloor.

“There are a lot of conversations about the real risks and unanswered questions about ocean mining,” says McCauley. “There’s now more than 90 NGOs that have come out and said that we need a moratorium on ocean mining and we shouldn’t be sprinting to do this until we are able to answer some of the serious questions about the impact of mining on ocean health.”

The deep sea is one of the least-explored places on the planet, but we know that these dark depths are teeming with life and are interconnected with other parts of the ocean ecosystem, despite often being 10,000 feet deep or more.

“These spaces out in the high seas, which include undersea mountain ranges, are really quite biodiverse and they’re full of very unique species,” says McCauley.

That includes “Casper,” a newly discovered, ghostly white octopus; the sea pangolin, a snail that lives on hydrothermal vents; and black coral, which can live thousands of years.

The deep seabed is also home to countless species we don’t even know exist yet and a large diversity of carbon-absorbing microbes that build the base of the ocean’s food chain.

Extracting minerals from the deep sea could put thousands of these species at risk from the direct impacts of the mining operations, as well as the associated light and noise. Plumes of sediment from discarded mining waste pose another danger.

“Those plumes could be quite large and persistent and could have a smothering effect on ocean life,” says McCauley.

That could even be bad for those of us onshore.

A report by the Worldwide Fund for Nature found that “the loss of primary production, for example, could affect global fisheries, threatening the main protein source of around 1 billion people and the livelihoods of around 200 million people, many in poor coastal communities.”

There’s also the potential that mining the deep seabed could affect our ability to cope with a changing climate. Currently the deep sea is what McCauley calls “a big bank of safely stored carbon.” He says “there’s a lot of unanswered questions about what would happen if you actually started redistributing that carbon back into circulation in the oceans. This isn’t the time that we want to be doing grand new experiments in an ecosystem like the ocean, which is our biggest ally in storing carbon.”

Another big concern is the ability of the deep ocean ecosystem to recover from disturbance.

“It’s such a special place biologically and physically,” he says. “It’s essentially a slice of the planet where life just moves slower and in a way that we don’t see anywhere else.”

Species at these depths tend to live a long time, take a while to reproduce and have low fertility rates. “And that means that life recovers more slowly than the other parts of the planet,” he adds.

A small-scale simulated mining experiment done in 1989 proved just that. “Scientists have returned to the site four times, most recently in 2015,” an article in Nature explained. “The site has never recovered. In the ploughed areas, which remain as visible today as they were 30 years ago, there’s been little return of characteristic animals such as sponges, soft corals and sea anemones.”

Alternatives

In order to keep heavy machinery off the ocean floor, McCauley says we can look to promising developments in battery technologies that are helping to reduce the amount of supply chain-constrained material, like cobalt.

Most of the people designing new battery technologies probably don’t have deep-sea biodiversity at the top of their minds, he says. “They’re designing it because these batteries are cheaper, more stable and have similar performance capabilities.”

Still, the end result could help make the case for holding off on plundering the ocean’s riches.

Cobalt has long been considered a key stabilizing component in lithium-ion batteries, but new chemistries have begun to whittle down the amount of cobalt needed. EV batteries containing the previous mix of equal parts nickel, manganese and cobalt in the cathode — or negatively charged electrode — can now be replaced with 80% nickel, 10% manganese and 10% cobalt. These batteries, known as NMC 811, are already being used in electric vehicles in China.

“So we’ve reduced the amount of cobalt from 33% down to 10%, but if you look at the projections of electric vehicles by 2030, it’s going to be hard to have even 10% cobalt in the cathode because of the limited cobalt reserves that are available,” says Matthew Keyser, a mechanical engineer with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

That means that new developments are now trying to move away from cobalt entirely. But that may end up shifting demand to another metal — nickel, which is fast becoming the most valued mineral for EV batteries and could still put the ocean on the target list.

Batteries made with lithium manganese oxide or lithium iron phosphate are new alternatives that don’t require nickel, but Keyser says they’re still not ideal.

“They have lower energy densities and they don’t work as well in vehicles,” he says. “The ultimate thing that we’re all trying to [achieve] is a battery with lithium sulfur, because sulfur is widely available.”

Working out the kinks in that technology is still five or 10 years away, he estimates.

Beyond changing the chemical composition of batteries, we can also help reduce demand pressure on scarce minerals in other ways.

“Instead of mining the oceans we can do a better job of mining the wrecking yards where EVs will be, which is to say doing a better job with recycling batteries,” says McCauley.

Currently only about 5% to 10% of lithium-ion batteries are recycled. In part that’s because the process is still more expensive than acquiring most of the raw materials. It’s also complex because the different variations of lithium-ion batteries on the market today each require a different recycling process.

But earnest efforts are underway to sort that out. One is Redwood Materials, started by Tesla co-founder J.B. Straubel, which says it’s the largest battery recycler in North America and can recover 95-98% of elements in batteries like nickel, cobalt, lithium and copper.

There’s concern that recycling can’t meet short-term demand because there aren’t enough batteries ready for recycling yet, but researchers believe it will be useful as a long-term solution for reducing scarcity.

“Recycling is going to be key,” says Keyser. “It’s going to be very important in the future and we need to do better than what we’re doing right now.”

Research also suggests that demand for EV cars with higher driving ranges increases the size of the batteries needed and influences the materials chosen to make them. But we can shift our technology, personal expectations and driving behavior.

“The introduction of shared-mobility services and establishing thorough charging networks can … significantly reduce material demand from the transport sector,” the WWF report recommends. “Other technological developments that can reduce material demand are advances in widespread charging infrastructure to increase the range of small-sized battery EVs as well as improved battery management systems and software to increase battery efficiency.”

McCauley hopes that a combination of advances will help take the pressure off sensitive ecosystems and that we don’t rush into mining the seabed for short-term enrichment when better alternatives are on the horizon.

“One of my greatest fears is that we may start ocean mining because it’s profitable for just a handful of years, and then we nail it with the next gen battery or we get good at doing low-cost e-waste recycling,” he says. “And then we’ve done irreversible damage in the oceans for three years of profit.”

![]()