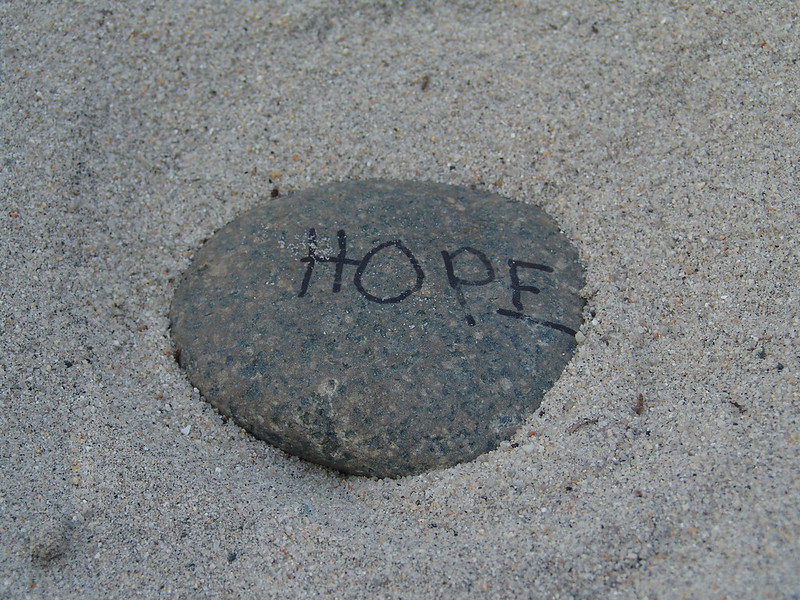

Sagebrush bulldozed for a housing development. A pipeline carved through grasslands. Forest felled for a road. Every 30 seconds in the United States, a football field-sized swath of nature is lost to development, according to research from the Center for American Progress.

This troubling trend runs counter to calls from scientists to protect more natural areas to mitigate against the effects of climate change and better protect plants and animals from extinction.

Current goals to protect biodiversity simply aren’t good enough, scientists say.

Targets set in the international Convention on Biological Diversity called for protecting 17% of land and 10% of the ocean by 2020. “These are interim measures that are politically driven but not science based and are widely viewed in the scientific literature as inadequate to avoid extinctions or halt the erosion of biodiversity,” according to research published in the journal Science Advances.

If habitat destruction and warming don’t peak by the end of this decade, we won’t be able to keep rising global temperature below the critical threshold of 1.5 degree Celsius, the researchers said. “It has become clear that beyond 1.5°C, the biology of the planet becomes gravely threatened because ecosystems literally begin to unravel,” the authors wrote.

We need to aim higher. And quickly. Efforts are now coalescing behind “30×30” — a global goal of protecting 30% of Earth’s land and water by 2030.

“30×30 has been discussed in scientific circles for quite some time in acknowledgement of the multiple crises on our hands — the extinction crisis and the climate crisis — both of which are magnified by the rate at which we’re losing nature,” says Ryan Richards, a senior policy analyst at the Center for American Progress.

In January the United States took a first step in moving the United States toward 30×30. A sweeping executive order from President Joe Biden on the climate crisis contained a mandate directing the secretary of the Interior and other relevant agency leaders to submit recommendations for how the federal government could conserve at least 30% of the United States’ land and waters by the end of the decade.

Initial findings are due later this month, but there’s no doubt that there’s much work to be done. Currently 26% of the country’s ocean waters are protected, but only 12% of U.S. lands.

“Nine years is not a very long time to protect essentially 440 million additional acres that still need to be conserved to reach that 30% goal,” says Erin Heskett, vice president of conservation initiatives at the Land Trust Alliance.

A big focus will undoubtedly be increasing the amount of federally protected public lands, possibly with a first step of restoring cuts by the Trump administration, which slashed more than 1 million acres from Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments in Utah. National parks, wilderness areas, wildlife refuges and national monuments are all important places that help protect biodiversity and sequester carbon to mitigate against climate change.

But there’s another important component, experts say: private lands. The Center for American Progress found that 75% of natural areas lost to development in the United States between 2001 and 2017 were on private lands, including farms, ranches and forests.

“That rate is five times higher than on federal or state lands,” says Richards. “So private lands are going to be one of the big pieces of the puzzle if you’re going to be successful in meeting those 30×30 goals.”

A Big Opportunity

When it comes to protecting private lands, there’s nowhere to go but up.

A mere 3% of protected areas in the country are on private lands, despite the fact that 60% of all land in the country is privately owned.

That’s bad news for biodiversity.

“Researchers have found that we’re losing habitat for threatened and endangered species twice as fast on unprotected private lands as we are on public lands, which is a big deal when you realize that a huge percentage of our threatened species live in places like the Southeast and areas outside of where we have a lot of federally protected public lands,” says Richards.

One way to begin protecting more private land is to ramp up existing programs that help local government agencies or land trusts buy private property outright or provide incentives for conservation easements.

Conservation easements, which are voluntary legal agreements where landowners are compensated for preserving — typically permanently — the conservation value of their property, already protect an estimated 40 million acres in the United States. And it’s proving to be a good investment of public money.

In Colorado conservation easements have set aside 1.5 million acres of land considered “crucial habitat,” which includes areas for Gunnison sage grouse and wintering range for elk. A report from Colorado State University found that each conservation dollar invested by the state has delivered $4-$12 of public benefits. Those benefits, often called “ecosystem services,” include groundwater recharge, flood control, water purification, and habitat for fish and wildlife.

“They are already popular, especially in the West where many landowners have a strong ethic of stewardship,” says Tyler McIntosh, a policy and design associate at the Center for Western Priorities. “Since people are already motivated to do this work, there’s an opportunity to structure our policy such that their voluntary efforts are worth it for them financially.”

Funding Sources

Several existing Department of Agriculture programs already help to boost conservation. One is the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program, which helps conserve wetlands and grasslands. Another, the Conservation Reserve Program, pays farmers to take land out of production and plant species to improve environmental health.

But McIntosh says interest in these programs exceeds most of their available funds.

That means Congress will need to allocate more resources to those programs and utilize other initiatives, such as the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which conservation groups fought last year to have fully funded by Congress.

Money from the fund — which is generated by offshore oil and gas leasing — can be used for acquiring new lands, such as through the Forest Service’s Land Acquisitions Program. But McIntosh says one important thing to remember is that most grants from the Land and Water Conservation Fund need to be matched at the state level. “It’s very important that states begin to set aside funds for conservation, too,” he says.

Exactly how much more money it will take to meet 30×30 conservation goals isn’t clear, says Heskett, but it will take efforts beyond the federal government.

“We’ll also need more from state governments, private philanthropy and conservation finance tools,” he says.

Combining permanent easements with short-term incentive programs could also help, say Arthur Middleton and Justin Brashares, professors in the department of environmental science, policy and management at the University of California, Berkeley.

“One such approach could be conservation leases with terms of 20 to 30 years that are palatable to landowners while providing meaningful protection,” they explained in an op-ed in The New York Times. “These programs would be less expensive than land purchases or easements, providing new ways for corporations and philanthropists to underwrite land protection at a scale much greater than can be achieved through the outright purchase of land.”

Additional Gains

Using private land to boost protected areas can also make nature more accessible and widens the geographic scope of where conservation happens.

The vast majority of federally protected lands are in the West, but by increasing protection on private lands in other parts of the country it can help conserve more plants and animals, as well as provide natural areas nearby millions more residents.

“Private land is often closer to communities than federal wilderness, national forests or even state lands,” found a report by the Center for Western Priorities. “For example, many city parks are protected by conservation easements. Additional benefits can include improved health, access to locally produced food, and opportunities for environmental education.”

But deciding which lands are conserved should also include identifying not just how much can be protected, but what kind of ecosystems.

“We feel that there’s an opportunity here to identify a significant portion of this goal that would invest in the lands and waters that are most resilient to climate change and would best allow animals and plants to find new places to thrive,” says Heskett.

One way to do that, he says, would be by using a tool developed by the Nature Conservancy called the Resilient and Connected Landscapes network, which identifies lands across the country that are expected to be the most resilient to climate change.

And any effort to improve conservation goals also need to be centered in equity.

“Native Americans and other peoples of color have been largely excluded from U.S. conservation policy, and many of them, living in cities, view public lands as remote and unwelcoming,” wrote Middleton and Brashares. “A successful 30 by 30 strategy must encompass needs as diverse as tribal priorities and urban green spaces in historically excluded communities.”

But if done well, a 30×30 conservation goal can help both diverse human communities and ecosystems.

“Our polling shows that the public is behind conservation,” says McIntosh. “And the question now is whether governments at state, local and federal levels are going to tap into that support and take advantage of this moment.”

![]()

Species name and description:

Species name and description: