On rare but breathtaking occasions, waves of opalescent clouds paint the twilight Antarctic sky in a mix of pastel hues. These “nacreous” clouds float at freezing stratospheric altitudes, where they mingle with the ozone layer and intense sunlight.

But that same sunlight that produces this spectacle also mixes with something less natural and less beautiful. When the sun’s unfiltered UV rays hit human-generated chlorofluorocarbons high in the stratosphere, they initiate a chemical reaction that cascades through those clouds and turns ozone into regular oxygen, weakening and depleting the ozone layer.

Because the ozone layer shades all life on earth from the most intense and carcinogenic UV radiation, our health and well-being depend on its integrity. Three decades ago this month, the world came together in the layer’s defense and formed the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. Today, the true benefit of that agreement is just starting to make itself known, thanks to a process that was set in motion by a bold and disruptive theory.

Theoretical Beginnings

As the son of a mathematics professor, Sherry Rowland was drawn to numbers and surrounded by books from a young age. Being somewhat precocious, he sailed quickly through his early education in central Ohio and began high school in 1939 at the age of 12.

During Sherry’s adolescent summers, his high school science teacher entrusted him to manage the local weather station, where he collected data on local temperatures and precipitation. During those summers in the early 1940s, the influence of his work on the global atmosphere several decades later must have been far from his active imagination.

Sherry would be more widely known as F. Sherwood Rowland by the time he became chair of the chemistry department at U.C. Irvine in 1964. There he crossed paths with Mario Molina, a recent PhD graduate with expertise in photochemistry. Aided by Molina and invigorated with a desire to explore new avenues of research, Sherry Rowland shifted his attention back to the sky.

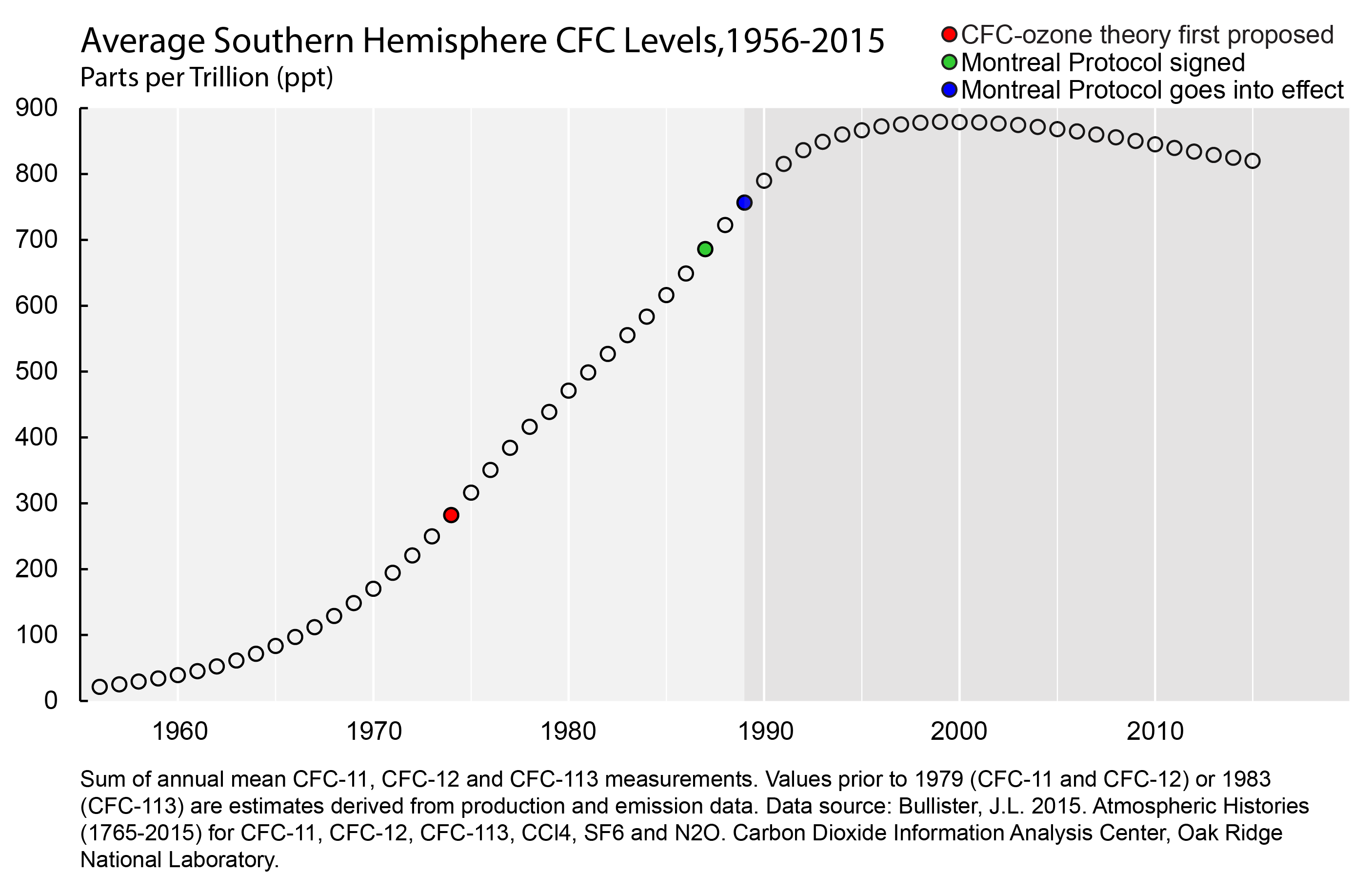

It had been just reported that nitrogen oxide compounds degrade under stratospheric conditions and affect the chemistry of the ozone layer. Being aware that human-generated chlorofluorocarbons were accumulating in the atmosphere, Rowland and Molina wondered if those compounds might also affect the ozone layer. They worked out the chemistry and found that chlorofluorocarbons would also theoretically degrade, and then release ozone-depleting chlorine. This chemistry and its potential implications were laid out for the first time by the duo in a 1974 report published in the journal Nature.

The Cold Backlash

Chlorofluorocarbons (also known as CFCs, or as Freon and other trade names) were first synthesized for refrigeration in 1928 — the year after Rowland was born. Because they were not only effective but also stable, nontoxic and nonflammable, they quickly replaced more hazardous 19th-century refrigerants. This enabled refrigeration technology to become more domesticated during the 1930s.

The availability of safe automotive and home air conditioning spurred the expansion of post-war suburbia. Air conditioning and refrigeration became all but ubiquitous in the developed world by the 1970s, and the CFC industry sat profitably on the crest of that wave.

Although the public knew very little about CFCs at the time, and even less about the layer of stratospheric ozone that was incidentally at risk, corporate resistance to Rowland and Molina’s 1974 report was swift and severe.

DuPont, the leading manufacturer of CFCs, responded on June 30 the following year with a full-page advertisement in The New York Times in which the company argued that it was too soon to be drawing any conclusions about the CFC-ozone theory. Regarding that theory, the ad proclaimed, “Hypothesis lacks support. Claim meets counterclaim. Assumptions are challenged on both sides. And nothing is settled.” DuPont’s well-financed public relations campaign continued promoting this narrative over the next decade.

Support from the scientific community for the CFC-ozone theory did not come immediately. It was no small claim to be made, and as Rowland and Molina’s contemporary Carl Sagan frequently said, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” Rowland was nevertheless convinced and concerned, and he felt compelled to put his reputation on the line and promote the theory publicly.

Fortunately, supporting evidence for the theory had been quietly accumulating for nearly two decades at a research station off the coast of Antarctica.

Extraordinary Evidence

As the Cold War was building in the 1950s, the United States, Soviet Union and eventually 65 other countries came to an agreement to allow scientific collaboration across political boundaries in the field of geophysics. This resulted in a flurry of research projects that began circa 1957 as part of what became known as “The International Geophysical Year.”

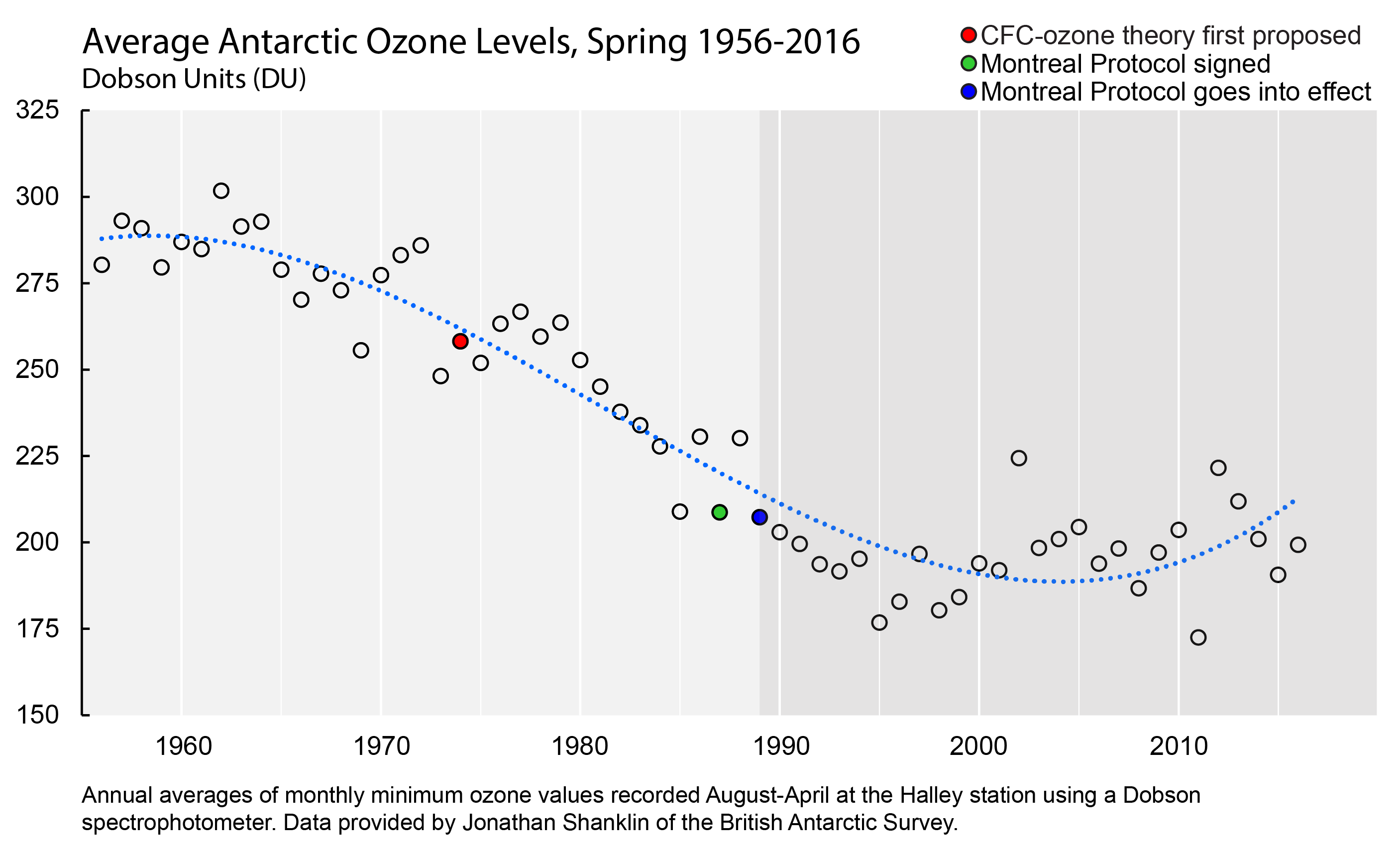

Many of those projects took place in Antarctica, including efforts to record the first continuous measurements of ozone levels in the earth’s atmosphere. By the 1980s, these measurements had begun to show a clear decline in atmospheric ozone. A 1985 scientific report was published in Nature that presented this data and demonstrated how the decline could be explained by increases in atmospheric chlorine.

That same year, NASA released the first satellite image of the ozone layer, including the lack thereof above Antarctica. This provided a stunning picture in color of what was suggested in data, and it gave rise to the phrase “ozone hole.“ Meanwhile, other support poured in independently from several academic and government studies, which cohered a consensus that paved the way for action.

From Vienna to Montreal

The year 1985 was also an inflection point for the political process. The first international talks on ozone depletion began that year at the Vienna Convention, coordinated by the United Nations. Meanwhile, DuPont and the CFC industry continued to dispute the science and campaign against regulations until it became apparent that CFCs could be economically replaced by other refrigerants that were more ozone-friendly.

Within the next two years, the discussions shifted in favor of gradually phasing out CFCs and other ozone-depleting chemicals, and a plan was put in ink. The proposed regulations on CFCs had bipartisan support in the United States under the Regan administration. Leaders from 24 nations signed on to the agreement in Montreal on September 16, 1987, and the Montreal Protocol went into effect on New Year’s Day 1989.

Eventually, the list of participants in the Montreal Protocol expanded to include 197 nations — practically every sovereign state in the world. It was the first treaty to ever receive universal ratification from every U.N. nation, and Kofi Annan later declared it “perhaps the single most successful international agreement to date.” Global CFC production was phased out by 2010 in accordance with the protocol.

Through all of this, Rowland remained actively involved in the science as well as the political process. Within 20 years, he went from an academic voice in the wilderness to a Nobel Prize recipient, alongside Mario Molina and atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen.

Slowly Reversing the Trend

Scientists expect that CFCs from decades past will remain in the atmosphere for decades to come before they finally degrade. The ozone hole, consequently, is a wound that has not yet healed, and will only do so slowly.

But already, there is evidence that it is on the mend.

During the last few years, Antarctic ozone measurements have begun tilting upward, as CFC measurements have begun to drop. Although ozone levels are naturally variable and temperature-dependent, the general trend appears to be reversing.

It is difficult to know the full impact of the Montreal Protocol on human health and the environment. But recent estimates suggest that by 2013, the Antarctic ozone hole would have been 40 percent larger, and by 2030 skin cancer rates worldwide would have increased 14 percent.

What we do know is that human activity can have a global impact on the environment. But we also know that what mankind is capable of destroying, mankind is capable of repairing when resources are shared, and science and policy work patiently together. The 30-year history of the Montreal Protocol and the series of events that preceded it, now prove that.

© 2017 Robert Lawrence. All rights reserved.

That growth in biodiversity, Thomas writes, hinges on speciation, which is the evolution of new, distinct species. It’s happening much more quickly than biologists previously thought — mostly through migration and subsequent diversification and hybridization of existing species into new, distinct species. According to Thomas, this rapid speciation is good news.

That growth in biodiversity, Thomas writes, hinges on speciation, which is the evolution of new, distinct species. It’s happening much more quickly than biologists previously thought — mostly through migration and subsequent diversification and hybridization of existing species into new, distinct species. According to Thomas, this rapid speciation is good news.

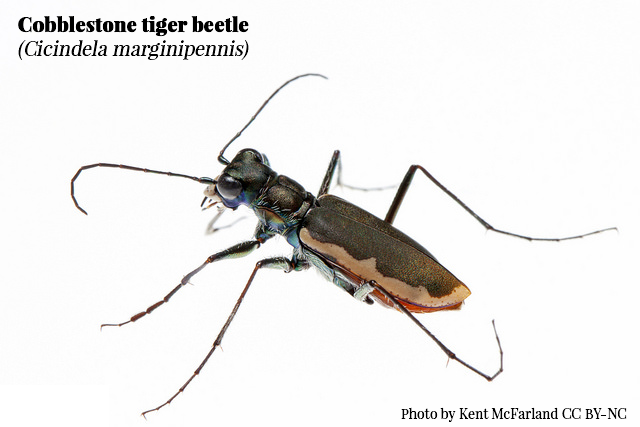

…to the somewhat less impressive fuzzy pigtoe mussel.

…to the somewhat less impressive fuzzy pigtoe mussel.

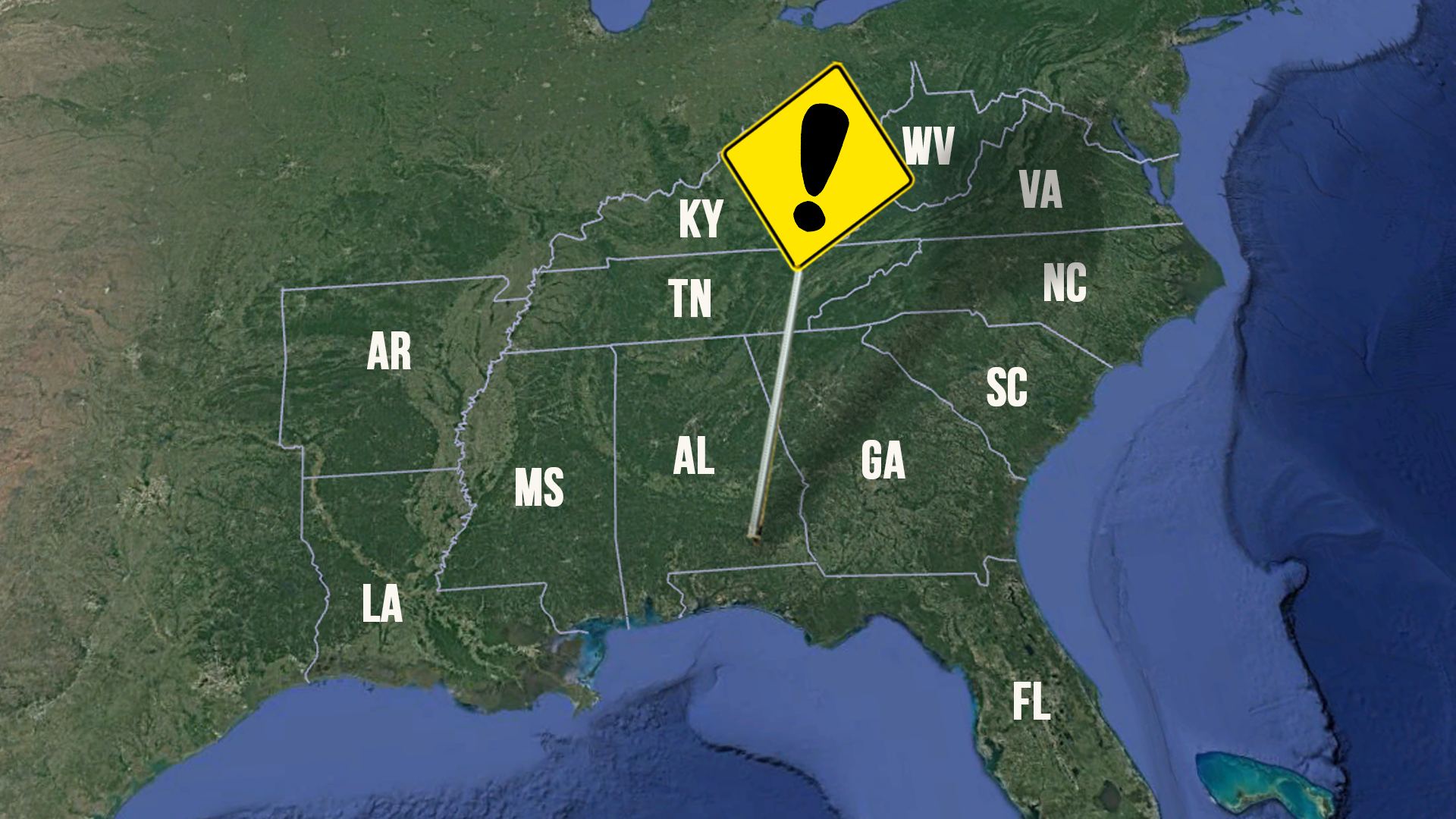

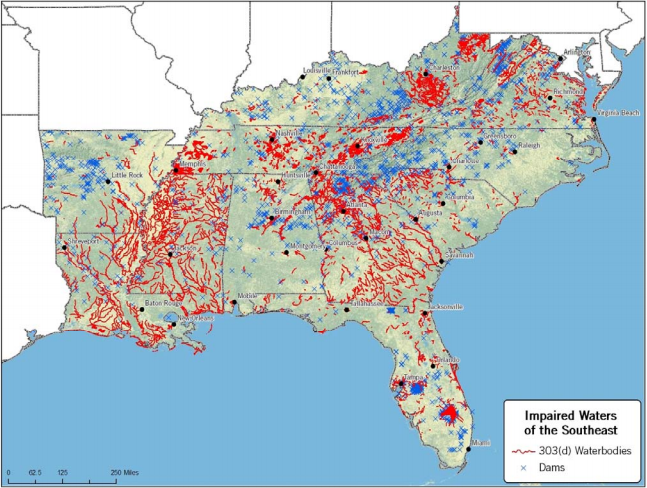

Among the region’s top threats, mountaintop removal mining destroys the tops of mountains overlying coal deposits using explosives and dumps the blast-debris into nearby valleys and waterways.

Among the region’s top threats, mountaintop removal mining destroys the tops of mountains overlying coal deposits using explosives and dumps the blast-debris into nearby valleys and waterways. This archaic and incredibly destructive process threatens the survival of hundreds of native, inter-dependent species that are vital members of their ecosystems.

This archaic and incredibly destructive process threatens the survival of hundreds of native, inter-dependent species that are vital members of their ecosystems.

Grand Canyon for Sale: Public Lands versus Private Interests in the Era of Climate Change by Stephen Nash

Grand Canyon for Sale: Public Lands versus Private Interests in the Era of Climate Change by Stephen Nash The Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the World by David R. Boyd

The Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the World by David R. Boyd Johnny Appleseed by Paul Buhle and Noah Van Sciver

Johnny Appleseed by Paul Buhle and Noah Van Sciver

How to be an Elephant by Katherine Roy

How to be an Elephant by Katherine Roy A World of Three Zeros: The New Economics of Zero Poverty, Zero Unemployment, and Zero Net Carbon Emissions by Muhammad Yunus

A World of Three Zeros: The New Economics of Zero Poverty, Zero Unemployment, and Zero Net Carbon Emissions by Muhammad Yunus Whale Song by Margret Grebowicz

Whale Song by Margret Grebowicz Critical Critters by Ralph Steadman and Ceri Levy

Critical Critters by Ralph Steadman and Ceri Levy