WASHINGTON— Few days go by without President Trump touting his “America First” agenda, which includes his ambitions to dramatically ramp up offshore drilling for oil and natural gas.

There’s some irony, then, that the first beneficiaries of these initiatives could be mostly foreign-based companies that stand to reap millions of dollars in revenue from conducting oil and gas seismic surveys in the waters off the East Coast.

An investigation by The Revelator reveals that four of these seismic survey companies are based overseas. Only one is based in the United States. The surveys are highly speculative ventures, to be conducted in a region thought to hold relatively low oil and gas reserves and appear unlikely to proceed without significant upfront funding from oil companies.

Our investigation also shows that despite decades of research on the impact of noise on marine mammals and other wildlife, there has never been a robust, ecosystem-wide examination of its effects. This gap in the understanding of regional impacts of seismic surveys on an array of marine life is contributing to ongoing debate within the marine science community on their impacts on oceanic species.

The oil and gas industry and the federally funded National Science Foundation, along with Columbia University’s prestigious Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, say the seismic testing causes no lasting harm to marine life. But other marine biologists and environmentalists say there is increasing evidence showing that the surveys do cause significant harm and therefore should not be conducted in the Atlantic.

“The (industry) claims there is no demonstrated effect,” says Douglas Nowacek, associate professor of conservation technology at Duke University Marine Laboratory in Beaufort, North Carolina. “But nobody has looked” thoroughly enough.

Opening up the Atlantic to Oil and Gas

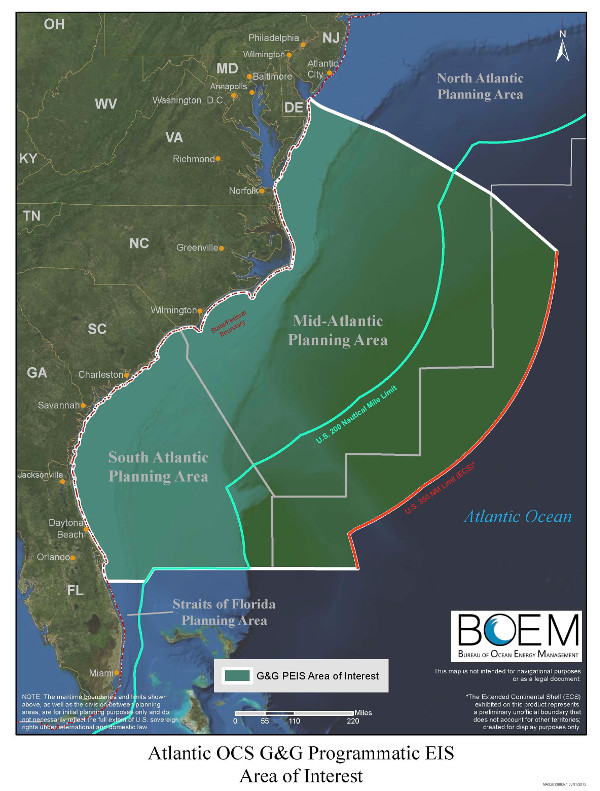

The National Marine Fisheries Service is currently reviewing the applications to conduct seismic surveys spanning 330,000 square miles of the Atlantic between New Jersey and Florida.

Trump issued an executive order this past April to open the mid- and south-Atlantic to potential oil and gas development. The order also directed the fisheries service to “expedite all stages” of seismic survey applications. Decisions on whether to proceed with oil and gas leasing in the Atlantic and to award seismic survey permits are expected later this year.

Trump issued an executive order this past April to open the mid- and south-Atlantic to potential oil and gas development. The order also directed the fisheries service to “expedite all stages” of seismic survey applications. Decisions on whether to proceed with oil and gas leasing in the Atlantic and to award seismic survey permits are expected later this year.

Seismic surveys use super-loud underwater blasts from powerful air guns to map the ocean floor in search of fossil fuels. The surveys are a crucial first step in determining whether there are sufficient oil and natural gas for energy companies to invest billions of dollars to develop offshore production platforms and onshore processing facilities. The sounds are roughly equivalent to a grenade blast and can be detected thousands of miles across the ocean.

The Trump administration’s plan to open the Atlantic for oil and gas exploration offers one of the largest seismic testing opportunities in the world. Offshore seismic surveys are conducted on a regular basis across the globe.

Applications to conduct these surveys have been submitted by Spectrum Geo and TGS, both headquartered in Norway; the French company CGG; and WesternGeco, a subsidiary of oil services giant Schlumberger that’s incorporated in the Caribbean island nation of Curaçao and has offices in Houston. The smallest of the five companies is Houston-based Ion Geophysical Corp.

Seismic survey cruises are generally required to have certified marine wildlife lookouts on watch and typically use “passive acoustic monitoring” systems to listen for marine mammal vocalizations. Seismic survey testing is stopped if marine mammals are detected nearby. But the monitoring is far from foolproof.

Conservation experts argue that more mitigation is needed to reduce the potential impacts of these studies that could harm not just wildlife but other industries, including commercial and sport fishing.

“Approving seismic blasting in the Atlantic would simply shift the conservation burden [for marine species] onto U.S. fisheries and others in this country, to profit what are mostly foreign companies,” Michael Jansy, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Marine Mammal Protection Project, tells The Revelator.

Seismic Survey Industry Struggles to Stay Afloat

The Atlantic seismic surveys would come at a crucial time for the seismic survey industry, which has been battered by three years of low oil prices. The industry suffers from overcapacity, bankruptcies, layoffs, declining stock prices and years of financial losses that have slashed its market by 60 percent since 2012, according to the trade publication E&P Hart Energy.

Trump’s support of this industry also comes at a time when the United States is approaching record domestic oil production, with surging exports lead by steady productivity increases from fracking in the West Texas Permian basin, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Atlantic reserves, by comparison, aren’t necessarily attractive to oil companies. Pavel Molchanov, senior vice president and equity research analyst at Raymond James & Associates Inc., told E&E News in July that the Atlantic leases are unlikely to spur major new activity. “Industry does not want to drill in those places right now because prices are relatively weak,” he said.

It also seems unlikely that the debt-laden seismic survey companies will proceed with the very expensive surveys unless they receive some upfront prefunding from oil companies willing to purchase the survey data, The Revelator’s review of the five companies’ public financial reports show.

At least one of the companies confirms this to be true. “If we have customer support, we will move forward with a seismic data acquisition program,” Susan Ganz, a spokeswoman for WesternGeco, stated in an email to The Revelator.

How Much Oil Are We Talking About?

Seismic surveys taken in the Atlantic between 1966 and 1988 indicate approximately 2.8 billion barrels of technically recoverable oil reserves exist, mostly in the mid-Atlantic. Only 2.4 billion barrels are considered economically recoverable at $100/barrel, nearly double the current price, according to a 2016 Bureau of Ocean Energy Management report. That’s just enough oil to meet current U.S. demand for about 120 days.

The industry is hopeful that these old estimates are incomplete. “Atlantic seismic survey data are needed to update resource estimates that are based on decades-old information,” a consortium of oil industry trade groups stated in an Aug. 17 filing to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. “With new seismic data in hand, decisions informed by science can be made as to the true resource potential in these areas.”

The current proposed round of Atlantic seismic applications calls for two-dimensional (2D) testing. But if new prospects are discovered, additional seismic surveys using more advanced 3D and 4D technologies could be conducted, providing a four-dimensional view of the ocean floor, industry experts say.

Environmental groups question why it’s necessary to issue Atlantic seismic permits to all five companies, which will conduct surveys in overlapping areas and in some cases, at the same time. The companies will pay nothing to the federal government for the potential harm that could result to marine life.

To minimize the impact on species, environmentalists urge the sharing of survey data from a single company rather than allowing multiple companies to acquire data that would then be subsequently sold to oil and gas companies.

“Under the law, cumulative impacts (from seismic surveys) are not taken into account,” says Ingrid Biedron, a marine scientist with Oceana, an environmental group working to protect the world’s oceans.

A Seismic Split in the Science Community

Offshore seismic surveys use a series of air guns clustered in arrays and dragged underwater behind survey ships. The guns release compressed every 10 to 12 seconds, creating a sonic wave.

The testing continues 24 hours a day for months a time. The sound can travel several thousand miles through the ocean depending on water temperature, salinity and the ocean floor contour.

The sound waves are generally directed downward and bounce off subsurface geological formations. Hydrophones dragged behind the ship then receive the reflected sound. Sophisticated computer programs use the data to generate maps of the ocean floor, showing where potential oil and gas reserves may be located.

How does all this affect marine life? That’s still a matter of controversy.

The government previously considered the impact on marine life as potentially consequential. President Obama last December permanently withdrew the north- and mid-Atlantic from offshore oil and gas development because of the high potential for environmental damage and low amount of estimated hydrocarbon resources. Trump’s April executive order partially reverses that decision.

Before that, in the wake of Obama’s decision, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management canceled six seismic survey applications. The agency’s then-director Abigail Ross Hopper stated this past January that the value of the potential information from “new air gun seismic surveys in the Atlantic does not outweigh the potential risks of those surveys’ acoustic pulse impacts on marine life.”

Oil-industry trade groups disagreed and stated in public comments filed in July with the National Marine Fisheries Service that “there has been no demonstration of any biologically significant negative impacts to marine life” from seismic surveys and that the proposed Atlantic surveys “will have no more than a negligible impact on marine mammal species” or on fisheries.

The oil industry’s contention that seismic testing causes negligible impact on marine life is supported by the National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences. The science foundation owns the seismic survey research ship Marcus G. Langseth, operated by Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory’s Office of Marine Operations. The foundation provides about $10 million a year for offshore seismic survey research conducted by academic scientists across the country using the Langseth.

The Langseth serves as the national seismic research facility for the U.S. academic research community. The ship’s seismic research “provides a view of the Earth’s interior that is unmatched in clarity, quality, and detail by any other method,” a brochure issued by the Lamont-Doherty observatory states. “As a result, a wide array of key Earth processes can now be studied in all three dimensions.”

The National Science Foundation and the observatory have repeatedly stated in seismic survey applications to the National Marine Fisheries Service that the tests do not cause lasting harm to marine life, a position the federal regulatory agency has generally echoed.

In an October 2015 draft environmental analysis for a proposed seismic survey in the south Atlantic, the observatory’s environmental consultant concluded that the 42-day survey using an array of 36 air guns with total discharge of 6,600 cubic inches would have little impact on marine mammals. The size of that air gun array is comparable to the ones used by the five companies seeking Atlantic permits.

“It is unlikely that the proposed survey would result in any cases of temporary or permanent hearing impairment, or any significant non-auditory physical or physiological effects,” stated the observatory report, which was prepared by an Ontario-based environmental research firm called LGL Ltd. “If marine mammals encounter the survey while it is underway, some behavioral disturbance could result, but this would be localized and short-term.”

The National Marine Fisheries Service published a comprehensive assessment of seismic surveys on marine life in April 2016. The report was in response to a request for a permit to conduct a 60-day seismic survey in the south Pacific.

The fisheries service “does not anticipate that serious injury or mortality would occur as a result of Lamont-Doherty’s proposed seismic survey in the southeast Pacific Ocean,” the report stated.

“Lamont-Doherty’s proposed activities are not likely to cause long-term behavioral disturbance, serious injury, or death, or other effects that would be expected to adversely affect reproduction or survival of any individuals.”

Mounting Evidence of Significant Impact

But ongoing scientific research — often conducted in controlled settings — is compiling an increasing body of evidence that seismic surveys have negative impacts on marine life, with a chorus of scientists issuing dire warnings.

“Opening the U.S. east coast to seismic air gun exploration poses an unacceptable risk of serious harm to marine life at the species and population levels, the full extent of which will not be understood until long after the harm occurs,” 75 marine biologists stated in a 2015 letter sent to President Obama.

Researchers in Australia announced earlier this year they found that the seismic blasts killed zooplankton, raising concerns about the impact on the basic component of the ocean nutrient cycle.

On a larger scale, the endangered North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) is known to be sensitive to seismic generated noise and marine scientists fear any impact on its behavior — from decreased foraging to reproduction declines — could plunge the species toward extinction. The species experienced a spike of deaths reported earlier this year, primarily from entanglements with fishing gear, pushing the population below 500 whales.

The International Whaling Commission scientific committee concluded in 2005 that seismic surveys can cause “population level impacts.” The Convention on Biological Diversity stated in 2012 “there are increasing concerns about the long-term and cumulative of noise on marine biodiversity.”

A 2013 review on the impact of seismic air gun surveys on marine life found that “seismic air guns are the second highest contributor of human caused underwater noise in total energy output per year, following nuclear and other explosions.”

For years the government resisted even conducting significant studies on the possible impact of seismic surveys on marine mammals. It was only after environmental groups, including the Center for Biological Diversity, publishers of The Revelator, sued federal agencies that an Environmental Impact Statement on the impacts of seismic testing in the Gulf of Mexico was conducted.

That study clearly shows there are impacts. And in some cases, the study found, they can be severe. But the research was far from definitive and relied heavily on underwater robots to measure sound impacts. But the impact is harder to measure for marine mammals, which often have the ability to move away from loud sound sources, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

Still, the report estimated that 31.9 million marine mammals in the Gulf of Mexico could be “moderately” harassed by oil and gas seismic surveys over 10 years. That includes 8 out every 10 members of the Gulf’s endangered sperm whale population.

The report concluded, however, that “the best available information, while providing evidence for concern and a basis for continuing research, does not, at this time, provide grounds to conclude that these surveys would disrupt behavioral patterns with more than negligible population-level impacts” (chapter 4-57).

The Gulf of Mexico has been routinely subjected to seismic surveys for decades but without a comprehensive examination of its impacts in marine life.

“Nobody has studied whether seismic on the scale of the Gulf of Mexico impacts the populations of marine mammals, turtles, fish, whatever,” says Nowacek, who is among the world’s leading scientists studying the impact of sound on marine life and has testified before Congress.

Burden of Proof

The lack of definitive information on the impacts of seismic surveys on marine life has given industry an advantage when it comes to obtaining permission from the National Marine Fisheries Services to issue Incidental Harassment Authorization permits to conduct the surveys, experts say.

The permits allow seismic survey companies to “incidentally but not intentionally harass marine mammals.” The agency typically issues the permits with stipulations that “prescribe monitoring, reporting, and mitigation measures to minimize the impacts of the surveys to marine mammals.”

Marine scientists opposed to seismic testing say the industry and National Science Foundation’s position that seismic surveys cause no lasting damage to marine life is based on a faulty premise.

Nowacek says the standards should be revised by requiring applicants to prove that the testing causes no serious harm to marine life, rather than forcing environmental groups and university marine biologists with limited funding to conduct decades of research that, while showing negative impacts on individuals, remain inconclusive on an ecosystem level.

“You have some tool, some technique of sampling, and it’s a good tool for what it does,” Nowacek says. “But why is the burden of proof that somebody has to show that there is a severe negative impact instead of the other way around? We should be having a discussion about where the burden of proof lies.”

That discussion is not currently part of the seismic testing application process in the mid-Atlantic, nor is it expected to be.

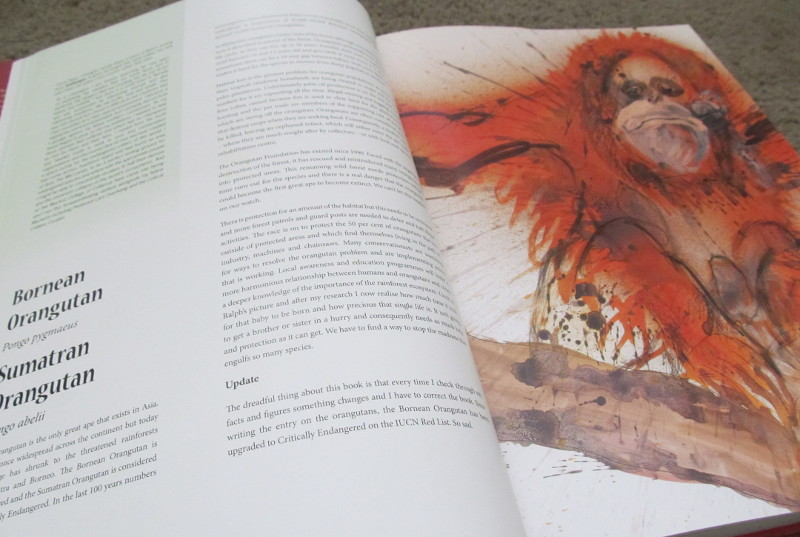

That process involves Steadman and Levy trading a constant barrage of jokes, insults, barbs, slings, snipes and burns, along with the more-than-occasional pun.

That process involves Steadman and Levy trading a constant barrage of jokes, insults, barbs, slings, snipes and burns, along with the more-than-occasional pun. “He stole that word off of me,” Steadman accuses gruffly, as the three of us talk over Skype.

“He stole that word off of me,” Steadman accuses gruffly, as the three of us talk over Skype.

Our night’s sleep in the Arctic Joule is fitful; our overindulgence runs through all of us like a thunderstorm. By seven in the morning, even with both hatches open, lighting a match in the cabin would blow us out like dirt from that Siberian crater. The roar of the Jetboil pulls me out. Frank’s already up, down jacket on, preparing coffee. “You like a cup?”

Our night’s sleep in the Arctic Joule is fitful; our overindulgence runs through all of us like a thunderstorm. By seven in the morning, even with both hatches open, lighting a match in the cabin would blow us out like dirt from that Siberian crater. The roar of the Jetboil pulls me out. Frank’s already up, down jacket on, preparing coffee. “You like a cup?”