What will future sea-level rise look like in coastal areas? For many people, it can be hard to visualize on-the-ground impacts from scientific projections. But people in southeast Virginia have a good idea of what to expect. The sea isn’t just lapping at the heels of communities there, residents are already regularly knee-deep in floodwaters.

Due to both rising seas and sinking land, Virginia has the fastest rate of relative sea-level rise on the East Coast. Add in flat topography and increasing rainfall, and what’s commonly referred to as “nuisance flooding” has become more than just an inconvenience — it’s now a national security risk and an economic threat.

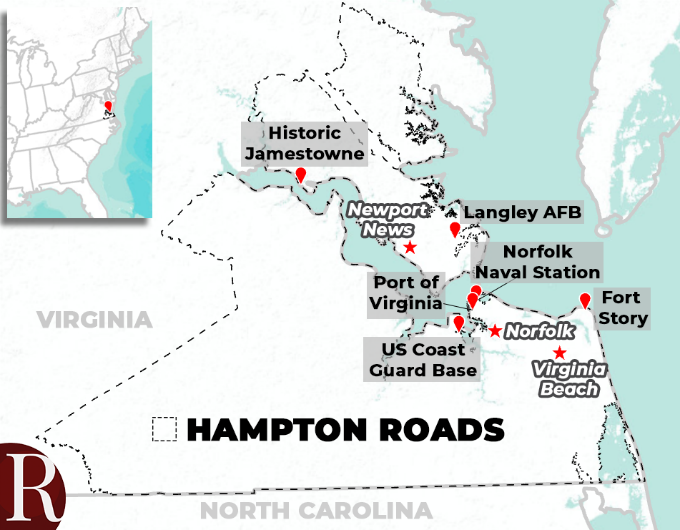

The Hampton Roads region of southeast Virginia is home to the largest active naval base in the world, more than a dozen military installations, one of the biggest ports on the East Coast and a robust tourism economy — all of which are threatened by too much water.

As state and local governments wrestle with how to solve the problem, Virginia is emerging as an important case study in dealing with climate impacts that may be years or decades away for other coastal communities.

As state and local governments wrestle with how to solve the problem, Virginia is emerging as an important case study in dealing with climate impacts that may be years or decades away for other coastal communities.

The state took two important steps forward recently. On Nov. 2 Gov. Ralph Northam issued an executive order to increase Virginia’s resilience to natural hazards and extreme weather. And earlier this year the state legislature mandated the creation of a new cabinet-level position to advise the governor on sea-level rise issues — the first such position in the country.

The two actions “establish the state leadership that we need to address the regional threats posed by sea-level rise,” says Elizabeth Andrews, director of the Virginia Coastal Policy Center at William and Mary Law School.

The Problem

Virginia missed the worst of hurricane season this year as Florence lashed neighboring North Carolina and Michael pummeled nearby Florida. And while Virginians may have breathed a collective sigh of relief, the state still has to grapple with a slower-moving and longer-term disaster.

The first part of the problem is rising seas. In Hampton Roads, water levels have increased 1.5 feet in the past century, according to a report from the University of Virginia.

One of the biggest contributing factors is climate change, which is melting ice caps and glaciers. The warming of ocean water is also causing it to expand. “Together these processes are believed to have added over half a foot to ocean levels in the past century,” according to a scientific report on recurrent flooding submitted to the Virginia General Assembly in January 2013. “Both of these processes have increased recently, and now are adding to the oceans’ volume at about twice the former rate.”

Another factor is that the land in coastal Virginia is sinking. Some of this is human-influenced in areas where communities have over-pumped groundwater, causing the aquifer to compact and the land above to subside. But another factor is natural — the Earth’s crust is continuing to adjust after glaciers melted during the last ice age, and it’s causing a sinking in coastal areas of the mid-Atlantic.

The problem is further compounded by changing ocean dynamics, including a slowing of the Gulf Stream, another impact of rising global temperatures. For the mid-Atlantic states this means there’s less pressure to help move water away from the coast, and it’s contributing to higher water levels in the area.

This combination of factors is already making coastal flooding worse. Roadways near the shoreline in southeast Virginia used to be inundated with floodwaters a couple of times a year due to high-tide events, but now it’s closer to 10 times a year, says Jon Derek Loftis, an assistant research scientist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Nuisance tidal flooding has shot up 325 percent since 1960.

Another factor is an increase in the amount of rain. Extreme precipitation events have increased 33 percent, and these severe storms are now dumping more water. Seven out of 10 of the most significant storms affecting Virginia since 1933 have occurred in the past 13 years. This means that even inland streets are now flooding as the ground becomes too saturated to absorb water. In some cases, higher water levels are pushing tidal water up through sewer systems into city streets instead of moving water in the opposite direction out to sea.

As bad as things are now, they’re only expected to get worse. By 2050 sea level is likely to be another foot higher, according to recent estimates from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. By the end of the century, predicts the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, seas could be four feet higher in the region, but with unchecked climate change that could be eight feet or more.

What’s at Stake

Sit in a beach chair facing the water at First Landing State Park in Virginia Beach and the drivers of the region’s economy are on full display.

Cargo ships lumber by, heaped with coal or stacked containers heading from the Port of Virginia, the sixth biggest port in the country. Flip-flop-clad tourists amble up and down miles of beaches, contributing $1.4 billion annually to the economy of Virginia Beach alone.

Military jets thunder overhead during training exercises. Every branch of the U.S. military, including the world’s largest active naval base, is here, making it “the largest federal presence outside of Washington D.C.” and the source of 40 percent of the region’s employment, says Ann C. Phillips, the retired U.S. Navy rear admiral who just filled Virginia’s newly created coastal adaptation and protection position as special assistant to the governor.

Sea-level rise threatens all of this.

The economic damage from annual flooding and coastal storms is anticipated to triple by 2060. A 2017 report from the Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Flooding Resiliency found that the region’s “tourism industry is highly vulnerable to recurrent flooding, severe coastal storms and hurricanes due to the infrastructure’s proximity to the coast.”

And it’s not just visitors; 164,000 people living in the region are at risk from coastal flooding impacts. That number is expected to nearly double by 2050, according to an analysis by Climate Central.

When it comes to safeguarding military interests, that means protecting bases, but also “making sure there is access to the base for employees who work there and for the utilities that have to run there,” says Andrews. The federal government will need to ramp up coastal resilience efforts, but so too will municipalities.

State Action

Many of the crucial solutions to combat rising seas and recurrent flooding will need to come from local governments, and a number of projects are already underway, but there’s a key role for the state to play, too.

The interest of state legislators was first piqued in 2013 with the report on recurrent flooding. “That got everyone’s attention in the legislature,” says Andrews, who added that officials realized the issue was serious and that it was only going to get worse.

Following the report, state legislators took a number of steps, including the creation of Phillips’ position.

It also created a joint coastal flooding subcommittee to address coastal flooding issues and the need for potential new legislation. The Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Flood Resiliency, a partnership among Old Dominion University, the College of William and Mary, and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, was also established to consolidate research efforts and funds.

Then in 2016 a law was passed to create the Virginia Shoreline Resiliency Fund, which will provide low-interest loans to help make coastal properties more resilient. “We think it’s one of the first to allow funds to be used to mitigate against future flood risk and not just to make repairs after a house has been damaged,” says Andrews. A good idea, but two years later the fund still remains empty without any money appropriated for it.

“We have a real opportunity and we must seize that opportunity and take action,” says Phillips, who believes the state can become a leader in coastal adaptation. “Or we’ll find ourselves with a decreased range of choices, and higher and higher costs.”

Skip Stiles, executive director of the Virginia nonprofit Wetlands Watch, believes Virginia is far behind on what it should be doing but expects more statewide efforts will ramp up soon under the leadership of Gov. Northam, who took office in January. “He has made the issue of sea-level rise a big part of his administration,” says Stiles.

The most promising development so far has been November’s executive order, which includes the creation of a Virginia Coastal Resilience Master Plan to help local government better plan for flood protection and initiate adaptation strategies. The order also taps the state’s secretary of natural resources to serve as the chief resilience officer and oversee a broad range of resilience strategies.

This includes encouraging nature-based solutions and land conservation where possible. The order also directs the state to aid municipal governments with technical assistance for planning, zoning and funding to increase local resilience and pre-disaster mitigation efforts.

“I am particularly encouraged by the executive order’s call for the creation of a Virginia coastal resilience master plan, which will enable us to better define and plan for the future risks,” says Andrews. “Too often in our world of fiscal limitations, tomorrow’s problems are overshadowed by today’s — but flooding in coastal Virginia is already happening now, and will only get worse.”

Stiles believes that this momentum to tackle sea-level rise and coastal adaptation issues won’t end with Northam’s four-year term. Increasingly the issue is receiving bipartisan support, something that has been tough to achieve in other states where climate change is a political lightning rod. “I think the expectation is that there will be some changes at the state level and the expectation is being held by both Democrats and Republicans,” says Stiles.

As the situation visibly worsens and impacts are hitting home, legislators are being forced to reckon with climate change, even if they don’t name it outright. Stiles says it’s gone from being an ideological issue to a constituent issue. “That’s what’s really started to accelerate progress on this,” he says. “And I don’t see that going away because I don’t see sea-level rise going away.”

Do you get our weekly email newsletter? If not, now’s the perfect time to sign up. This week subscribers can receive a free eBook edition of Corrupted Science: Fraud, Ideology and Politics in Science, the must-read new book by Hugo Award-winning author John Grant from publisher

Do you get our weekly email newsletter? If not, now’s the perfect time to sign up. This week subscribers can receive a free eBook edition of Corrupted Science: Fraud, Ideology and Politics in Science, the must-read new book by Hugo Award-winning author John Grant from publisher

So she did.

So she did. There is so much to love about being a farmer. Today I am in love with the opportunity to be close to the source of all wisdom, which I believe is the living Earth. And by having contact with the soil, there’s abundant communication that comes from the Earth about how we can best live in human community. For example, the mycelium connects the trees and transports sugars and minerals between them, weaving together life across divisions of species and geography. When we have contact with that, I believe that wisdom seeps into our consciousness and helps us know how to better be fully part of the interconnected web of life on Earth.

There is so much to love about being a farmer. Today I am in love with the opportunity to be close to the source of all wisdom, which I believe is the living Earth. And by having contact with the soil, there’s abundant communication that comes from the Earth about how we can best live in human community. For example, the mycelium connects the trees and transports sugars and minerals between them, weaving together life across divisions of species and geography. When we have contact with that, I believe that wisdom seeps into our consciousness and helps us know how to better be fully part of the interconnected web of life on Earth.

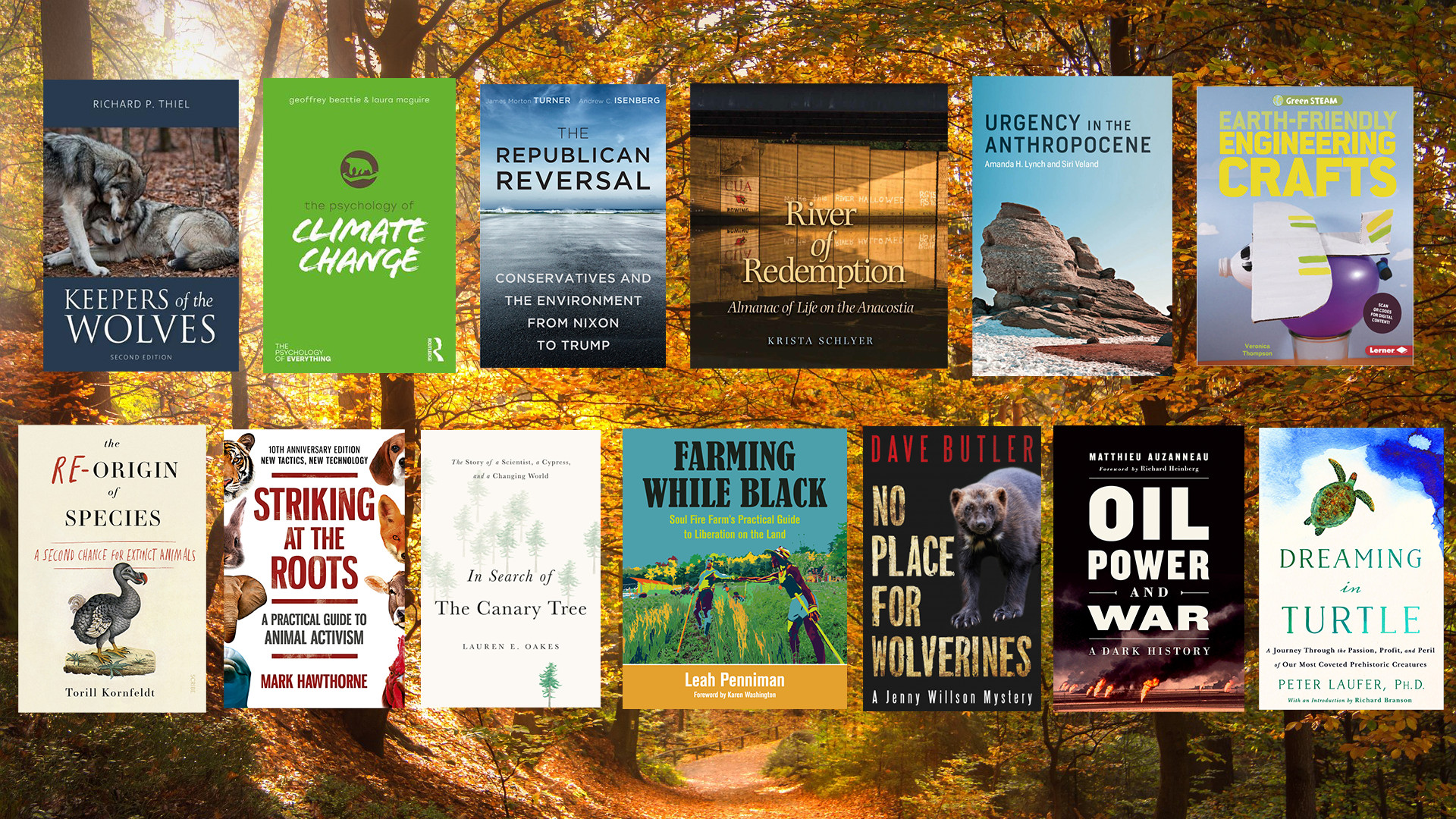

It’s election season, and we all need something to read after we’re done combing through our midterm voters’ guides. Here are our votes for the 16 best environmental books coming out this month, covering everything from wolves to wolverines and climate change to animal rights. Some of these books are intended for professional conservationists, while others may appeal to kids, mystery lovers, history buffs or fans of wildlife. And while many of these books are admittedly dark and depressing, you’ll find more than a few solutions in the mix as well. We hope you enjoy them. (Now if we can just get our politicians to read some of these books, too…)

It’s election season, and we all need something to read after we’re done combing through our midterm voters’ guides. Here are our votes for the 16 best environmental books coming out this month, covering everything from wolves to wolverines and climate change to animal rights. Some of these books are intended for professional conservationists, while others may appeal to kids, mystery lovers, history buffs or fans of wildlife. And while many of these books are admittedly dark and depressing, you’ll find more than a few solutions in the mix as well. We hope you enjoy them. (Now if we can just get our politicians to read some of these books, too…)