Crowded visitor centers, crumbling roads and aging buildings — those are the sights at some of America’s national parks lately, caused by years of chronic underfunding. Will the situation soon get even worse? The Trump administration has proposed stripping national parks’ funding even further, despite the fact that people are visiting our public lands more and more often.

John Garder, senior director of budget and appropriations at the nonprofit National Parks Conservation Association, says the majority of national parks have been short on cash for years.

“As a general rule, parks are underfunded,” Garder tells me in a telephone interview. “The two main issues are understaffing and the deferred maintenance backlog.”

The National Park Service maintenance backlog is estimated at $11.6 billion as of fiscal year 2018. Lawmakers and experts are huddling over the problem even as the president again proposes cutting the parks’ budgets.

In 2017 the National Park Service completed more than $519 million in maintenance and repair work. However, high visitation, aging infrastructure and budget constraints have kept the price for repairs high, according to the Department of the Interior.

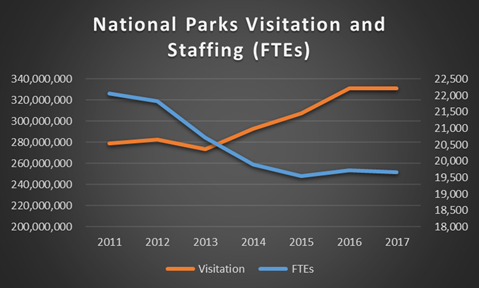

Ironically, the very popularity of national parks is driving the unmet budget need.

“The increase in visitation just makes the problem worse,” Garder says.

Crunched Budgets

The National Park Service’s budget was $3.4 billion in 2017, $2.9 billion of which came from Congress. The additional $594 million came from other sources, including $282 million generated by user fees.

The data provided by the National Parks Conservation Association show that while discretionary funding for the National Park Service has grown since fiscal year 2009, it has still not been enough to keep up with all maintenance and repairs amid increased visitation.

Discretionary funding includes all programs for which money is appropriated by Congress on an annual basis.

Only 117 out of 417 sites in the national park system collect fees. At the fee-collecting parks, 80 percent of the funds generated by fees remain in the parks where they were collected, while 20 percent go into a funding pool for other parks.

In recent years the budget appropriation process has become even more constrained, exacerbating the challenge of providing enough money to the National Park Service.

Garder says the Trump administration provided a “very damaging” budget blueprint for fiscal year 2018, asking Congress for cuts to the Park Service. Congress refused the administration’s proposed budget, which would have eliminated thousands of jobs at the agency, and instead provided it with more money than was originally proposed.

But Trump’s $2.7 billion 2019 budget blueprint, unveiled earlier this year, calls for a 7 percent budget cut to the Park Service. This would result in a loss of nearly 2,000 ranger jobs. The proposal also includes specific cuts to cultural programs, land acquisition and the Centennial Challenge, a program that manages philanthropic donations, according to the National Parks Conservation Association.

“National parks are a victim of what has become a broken appropriations system, and they are not receiving the support they should and not being prioritized,” Garder says.

Visitation Increasing

One site typifies the budget constraints felt across the country: Zion National Park in southwestern Utah.

This year more than 30,000 visitors flooded the park the Sunday before Memorial Day.

Zion is the only national park where management is considering a reservation system, as its visitation has been growing at a fast clip.

Just under 150,000 acres, Zion has only one main road that stretches for 6 miles. In 2017 the park had approximately 4.5 million visitors, making it the third most-visited national park in the country.

The park’s Twitter account has warned visitors often in recent weeks about parking restrictions.

A tweet on June 15 read: “Parking is full at the Zion Visitor Center and the lot has been closed. Visitors should not to go to the visitor center to park. Park in Springdale.”

Officials at Zion didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

Similar situations are occurring around the country. Last year 331 million people visited the 417 National Park Service sites across the country, according to the Department of the Interior.

Grand Canyon and Great Smoky Mountains national parks were the second and first most-visited, respectively.

Dana Soehn, spokesperson for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, says park visitation has increased by 25 percent over the past decade, while staffing has decreased by 23 percent.

To counteract the impact of the increased visitation, Soehn says, park officials started to remind visitors to travel to the park during less busy times like early mornings and mid-week, and have worked to make some of its most-used facilities more sustainable, including the park’s most popular trails.

Meanwhile the total deferred maintenance for Great Smokies is more than $215 million. While deferred maintenance is spread across thousands of physical assets, more than 75 percent of the repair needs, or $167 million, is associated with the park’s road system, Soehn says.

“This is not surprising when you consider the millions who choose to experience the Smokies from behind the driver seat every year,” she says.

Aging buildings are another primary concern in the Smokies, accounting for 8 percent of repair needs, or $16 million. The current deferred maintenance backlog for the trails system exceeds $16 million, which accounts for 7 percent of the park’s total deferred maintenance needs.

In 2018 and 2019, Soehn tells me, the park is embarking on a $2.5 million public-private partnership opportunity to fund deferred maintenance needs for the infrastructure of 9 radio repeater sites, which help the park ensure a safe visitor experience for visitors and safe operations for field employees.

Grand Canyon National Park, which saw more than 6.2 million visitors in 2017, has over $329 million in deferred maintenance. That figure includes The Trans-Canyon Pipeline, which carries water to the South Rim and its visitor centers and hotels. The pipe’s condition continues to deteriorate as it leaks and breaks.

The deferred maintenance backlog at Yosemite National Park in California currently stands at over $582 million.

Scott Gediman, spokesperson for Yosemite, says the park’s critical needs include three wastewater-treatment plants.

Similarly to Great Smokies, which receives outside help, Yosemite gets help from Yosemite Conservancy, a nonprofit organization that provides grants and supports the park’s 750 miles of trails. Most recently, Gediman says, the conservancy donated $20 million toward the renovation of Mariposa Grove, a sequoia grove that reopened in mid-June.

When asked if the park has enough staff to manage all of its visitors, Gediman says they are able to operate the park with its current 700-800 employees. “We could always use more people, but we have a very talented and dedicated staff and we feel that we are able to protect the park.”

Yellowstone National Park, meanwhile, needs over $800 million to address its maintenance backlog. The most pressing issues revolve around visitors services, says park spokesperson Neal Herbert.

“Those include constant repair and upkeep to roads, historic structures, water, wastewater, trails and boardwalks,” Herbert says. “For example, thermal basins change constantly and boardwalks need to be moved.”

This year’s Memorial Day contributed to May 2018 being the busiest May ever recorded in the park.

“Visitation has increased by 37 percent over the last five years,” he says. “This increase creates challenges for park staff, facilities, visitors, and the resources people come here to enjoy. Right now we’re collecting data on visitor expectations and how they move through the park.”

Possible Solutions

Several bills aimed at reducing maintenance backlog at the National Park Service are currently making their way through Congress.

The National Park Service Legacy Act, introduced by U.S. Sens. Mark R. Warner (D-Va.) and Rob Portman (R-Ohio), would allocate $500 million annually from revenues that the government receives from oil and natural gas royalties into a National Park Service Legacy Restoration Fund until 2047.

Rachel Cohen, communications director for Sen. Warner, says they are currently securing the steps for the bill to go forward, including discussions with the Senate Committee on Energy and National Resources.

Another measure geared toward reducing the financial woes of the National Park Service is the National Park Restoration Act, introduced by U.S. Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Rep. Michael Simpson (R-Idaho) on March 7.

Under the bill half of the excess revenue from controversial offshore and onshore drilling would be funneled to the National Park Service. The bill would create a fund for projects at national parks.

Ashton Davies, communications director for Sen. Alexander, says that there have been no hearings on the bill, but it has already received support from some Democrats. The legislation also would need to go through the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources.

Last year a proposed fee increase at the nation’s 17 most popular national parks caused a public outcry, as it would have nearly tripled vehicle entrance fees during peak seasons. Following the uproar the Trump administration scaled back its plans and implemented more moderate $5-10 fee hikes.

Garder argues that fee hikes alone can’t solve the issue. He says any further fee increases on top of the increases that have already taken place could drive away visitors.

“While fees play an important role in supplementing federal funds, they are no substitute, and they have to remain at a reasonable rate so as not to discourage visitation,” he says. “These are lands Americans own, and they have a right to visit them affordably. What’s most needed is a more robust federal investment.”

© 2018 Daria Bachmann. All rights reserved.