On September 16, 2017, environmental advocates Robert DiGiovanni, Jr., and Beth Fiteni slowly walked along West Meadow Beach in Stony Brook, New York, scanning their eyes over the sand for trash. Joining them were 14 other people — a mix of conservationists, college students and retirees — all helping pluck garbage off the beach. The group was just one of five taking part in cleanups on West Meadow Beach that day, all part of the Ocean Conservancy’s 32nd annual International Coastal Cleanup, a global effort to get people out of their houses and onto beaches to help clean up trash — mostly plastic.

This year nearly 800,000 other volunteers worldwide participated in the cleanup. It and other efforts to clean beaches have gained traction in the movement to address plastic pollution.

Most conservation experts, including DiGiovanni, founder and chief scientist at the Atlantic Marine Conservation Society, and Fiteni, founder and president of Green Inside and Out Consulting, support cleanup efforts. But while beach cleanups are surely an immediate help to coastal ecosystems, many such experts say the beach-cleanup model is flawed, and that it can actually encourage continued pollution of natural environments.

“What we’re doing — cleaning up our own mess — addresses just a symptom of the problem, not the problem itself,” says DiGiovanni. “In a week’s time, the same amount of trash we’ve cleaned up will wash right up, or be littered, onto the beach again.”

Together, DiGiovanni, Fiteni and their volunteers covered a 99,025-square-foot area of shoreline (92,000 square meters), cleaning up hundreds of plastic items such as lighters, plastic utensils and balloons. They recorded each item on a data sheet that they later sent to the Ocean Conservancy. To minimize their own trash footprint, DiGiovanni and Fiteni provided volunteers with reusable gardening gloves and plastic bags for collecting trash.

What the group collected was a very small portion of the 18,062,911 pounds (8,193,199 kilograms) of trash collected globally this year by all International Coastal Cleanup participants — which is an even smaller fraction of the 18,000,000,000 pounds of plastic debris that’s dumped, littered, or otherwise finds its way into the oceans every year, according to a recent study.

Although each participant in this cleanup didn’t collect a very large amount of trash individually, and more would soon replace what was picked up, it turns out it was the nature of the collected trash that mattered. Data on the trash that’s been cleaned up — during the international effort and also cleanups held by other nonprofits that collect and share plastic pollution data publicly, such as Hawaii Wildlife Fund, Trash Hero, Algalita, Plastic Change and 5 Gyres — can tell experts more about human plastic use and pollution patterns.

“This information provides information about debris ‘hotspots’ and identifies which items are most common on beaches,” says George Leonard, chief scientist at the Ocean Conservancy, which has the world’s largest and longest-running public database on marine debris. He adds that this data can be used by environmental advocates to promote policies such as better waste management infrastructure, bans on ecologically damaging items like plastic bags and foam and more scientific research on the plastic pollution problem’s scale and scope — and these actions are what might ultimately stem the tide of plastic pollution into the natural environment.

Government programs like the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Debris Program and the European Commission’s Marine Directive also perform routine research on plastic prevalence on beaches and in the oceans. Of particular concern is microplastic — tiny bits of plastic smaller than 5 millimeters in diameter that come from larger pieces of plastic that are broken up by the sun, waves and wind. These bits of plastic have been found to absorb and leach toxic chemicals, which can kill marine life when consumed.

And all of this environmental harm starts with people using plastic items on land. “Plastics enters the oceans through a wide variety of pathways on land, including illegal dumping, poor waste management, littering, laundering of textiles and use of personal care products that contain plastic ‘microbeads,’” says Leonard.

Creating plastic-alternative materials and handling plastic trash more responsibly are important components to reducing global plastic pollution. However, experts say that changing habits appears to be the key to stopping plastic pollution. And habits can change with greater awareness and policies aimed at curbing or stopping use of plastic products. Using data collected by the Ocean Conservancy and other groups, and also their personal experiences cleaning up trash from coastal ecosystems, ocean advocates and concerned citizens have swayed hundreds of municipalities and countries across the globe — from San Francisco, California, to Kenya, Africa — to ban or tax plastic bags, plastic utensils and/or plastic/foam food containers. Studies analyzing these bans, including those on the cities of Los Angeles and San Jose, have found them to be effective at reducing plastic bag use and litter.

Until all people understand how their actions are connected to plastic pollution in the natural environment and policies are implemented worldwide, beach cleanups are a good way of raising awareness, according to Allison Schutes, associate director for the Ocean Conservancy’s Trash Free Seas Program, which oversees the annual cleanup events. “Our hope is that at some point in the not-too-distant future we’ll no longer need the International Coastal Cleanup; our collective efforts to stop trash at its source will have succeeded.”

© 2017 Erica Cirino. All rights reserved.

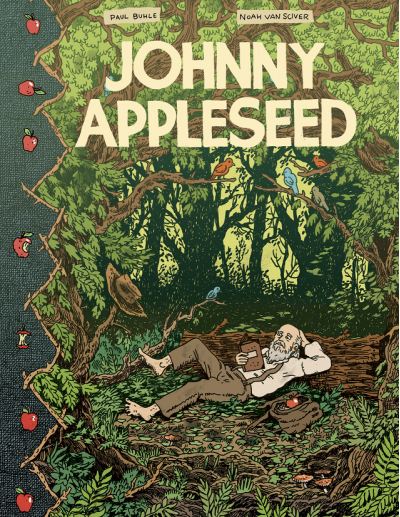

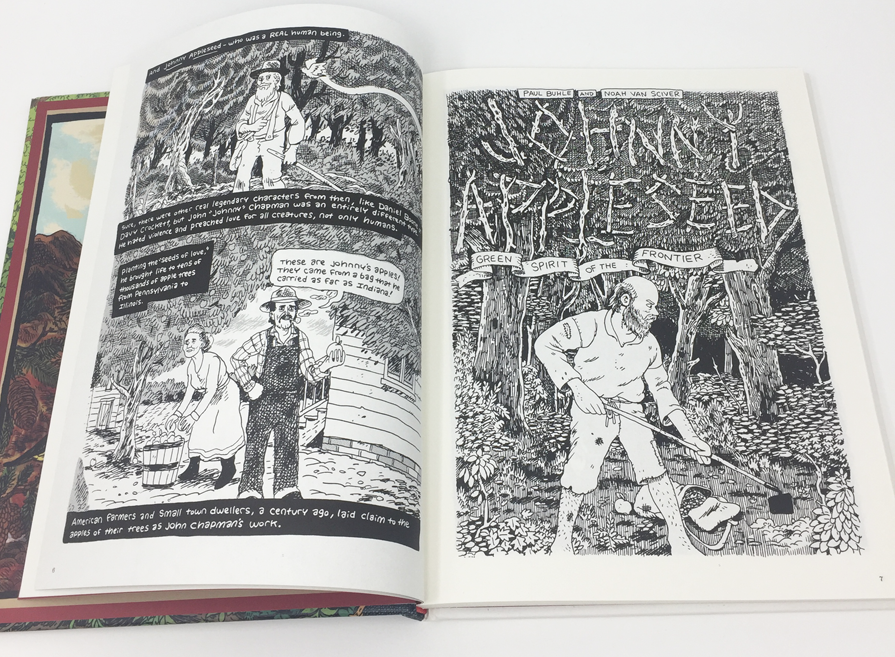

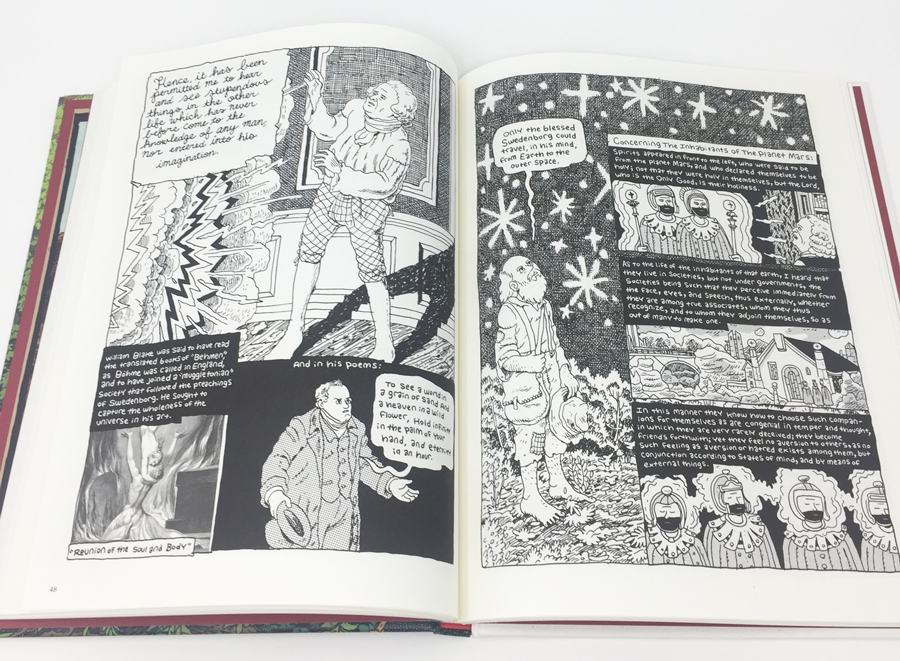

That’s the path taken by scholar Paul Buhle and cartoonist Noah Van Sciver in their new graphic novel, “

That’s the path taken by scholar Paul Buhle and cartoonist Noah Van Sciver in their new graphic novel, “

That’s where the larger bottlenose dolphins come in. Used by the U.S. Navy to locate so-called “aggressive swimmers” in combat situations, the dolphins have been trained to leap into the air when they encounter their targets, providing a visual cue for watchers on nearby ships.

That’s where the larger bottlenose dolphins come in. Used by the U.S. Navy to locate so-called “aggressive swimmers” in combat situations, the dolphins have been trained to leap into the air when they encounter their targets, providing a visual cue for watchers on nearby ships.

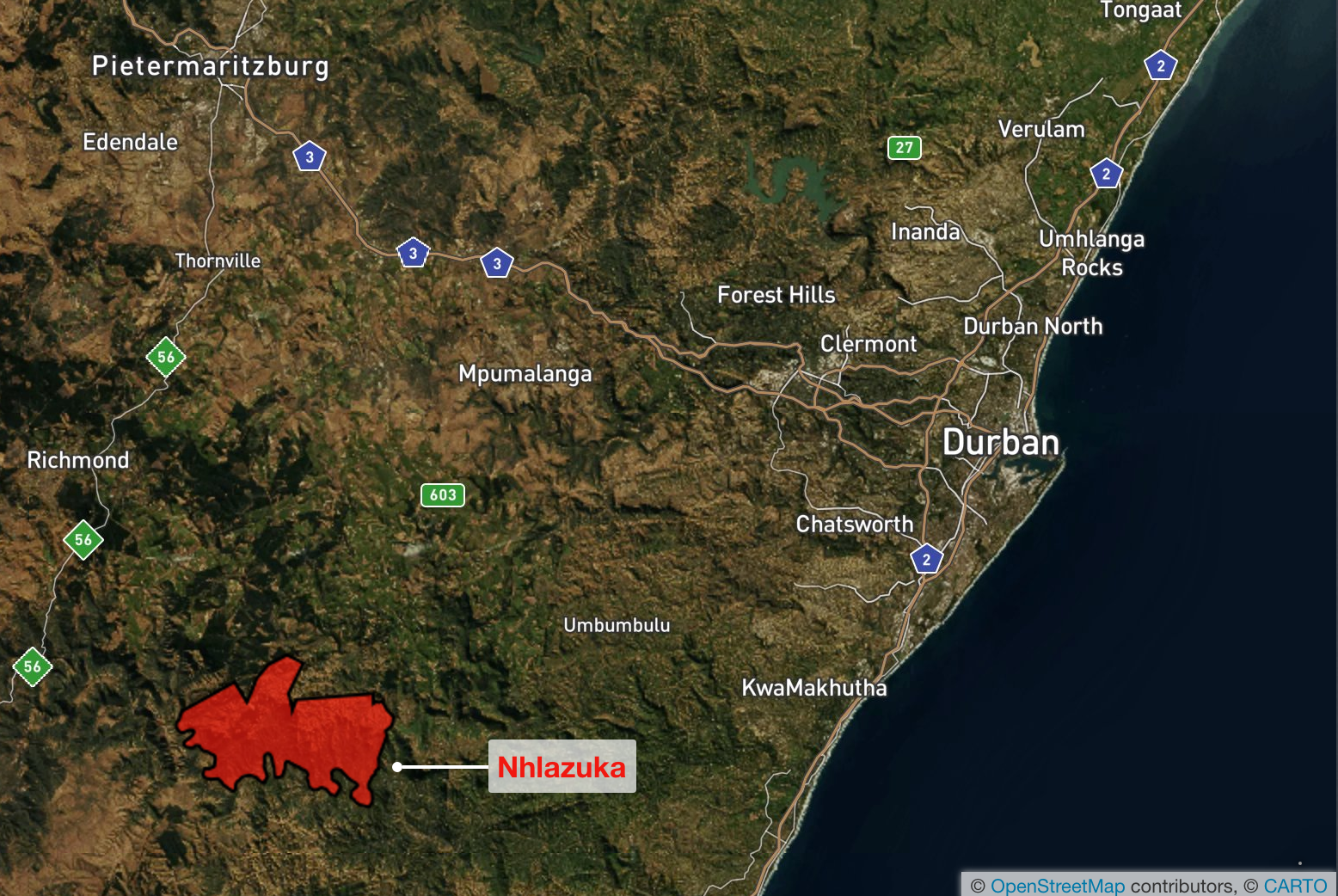

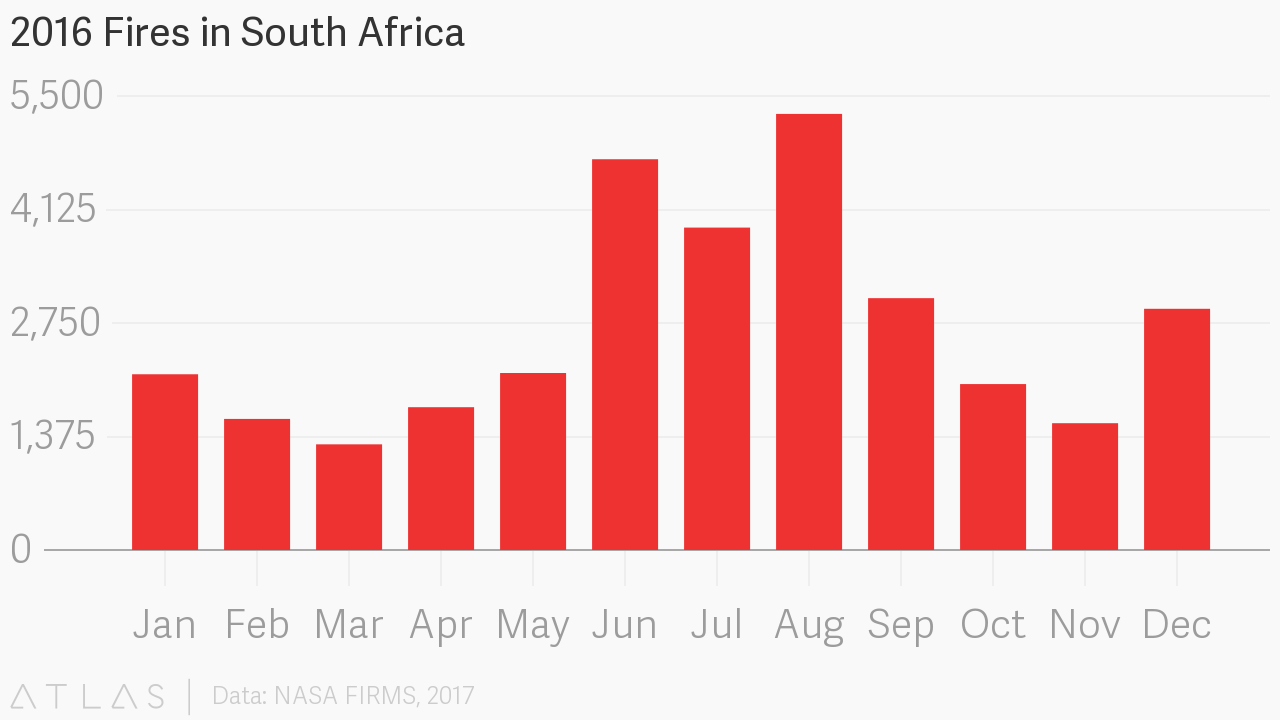

“When fires start in the valley, sparks fly up on top of the thatch and then the houses start burning,” says community member Bono Cwazibe.

“When fires start in the valley, sparks fly up on top of the thatch and then the houses start burning,” says community member Bono Cwazibe. “We have seen an increase in sudden and severe high-intensity weather events, such as storms, lightning and flooding, that risk human life and cause damage to the environment, infrastructure and people’s homes.”

“We have seen an increase in sudden and severe high-intensity weather events, such as storms, lightning and flooding, that risk human life and cause damage to the environment, infrastructure and people’s homes.” When the cameras detect smoke or a potential fire, the computers help the operator to zoom into the site and watch it live, to determine the direction of the fire, how far away it is and how threatening it is. Once it is confirmed that a fire is threatening, it is then positioned on a map to show its exact location.

When the cameras detect smoke or a potential fire, the computers help the operator to zoom into the site and watch it live, to determine the direction of the fire, how far away it is and how threatening it is. Once it is confirmed that a fire is threatening, it is then positioned on a map to show its exact location. Since the implementation of FireWise in 2014, he says, the number of fires in the Nhlazuka area have decreased. It takes on average five hours to put out a fire once it has spread and to date, there is only one known death due to fire that occurred in 2013.

Since the implementation of FireWise in 2014, he says, the number of fires in the Nhlazuka area have decreased. It takes on average five hours to put out a fire once it has spread and to date, there is only one known death due to fire that occurred in 2013.

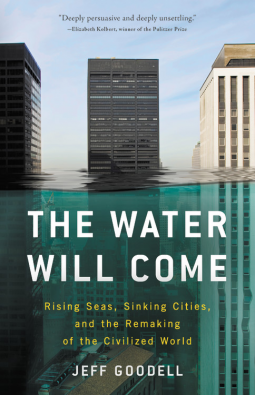

The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World by Jeff Goodell

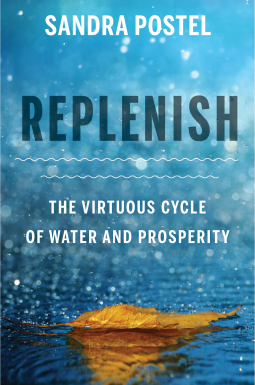

The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World by Jeff Goodell Replenish: The Virtuous Cycle of Water and Prosperity by Sandra Postel

Replenish: The Virtuous Cycle of Water and Prosperity by Sandra Postel American Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West by Nate Blakeslee

American Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West by Nate Blakeslee Science Comics: Dogs – From Predator to Protector by Andy Hirsch

Science Comics: Dogs – From Predator to Protector by Andy Hirsch Feed the Resistance: Recipes & Ideas for Getting Involved by Julia Turshen

Feed the Resistance: Recipes & Ideas for Getting Involved by Julia Turshen