About 25 miles from where the Rio Grande River meets the Gulf of Mexico, a dirt road hemmed by agricultural fields on either side leads visitors to one of the most spectacular birding sites in the country: The Nature Conservancy of Texas’ Southmost Preserve. The property’s entrance atop an earthen levee offers a view of one of only two large stands of native Mexican sabal palm and Tamaulipan thornscrub remaining in the United States. These 1,014 acres provide habitat for a number of other rare, threatened and endangered species and are an important layover spot for dozens of species of migrating birds.

Well before reaching the levee, though, visitors hoping to catch a glimpse of this magnificent landscape get an entirely different view: rows of 18-foot metal bollards four inches apart, stretching in both directions from the road.

Constructed in 2010, this section of border barrier sits up to a mile from the actual Texas-Mexico border, according to The Nature Conservancy’s Sonia Najera, and runs north of most of the preserve.

“It is a very accurate statement to say I’m not a fan of the barrier,” Najera says.

She has plenty of company here. Other non-fans include local birding guides; owners of land adjacent to, behind, and in sight of, wall sections; and tourists, scientists and former wildlife refuge employees (current employees cannot officially comment). Statewide 61 percent of Texas adults oppose a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border.

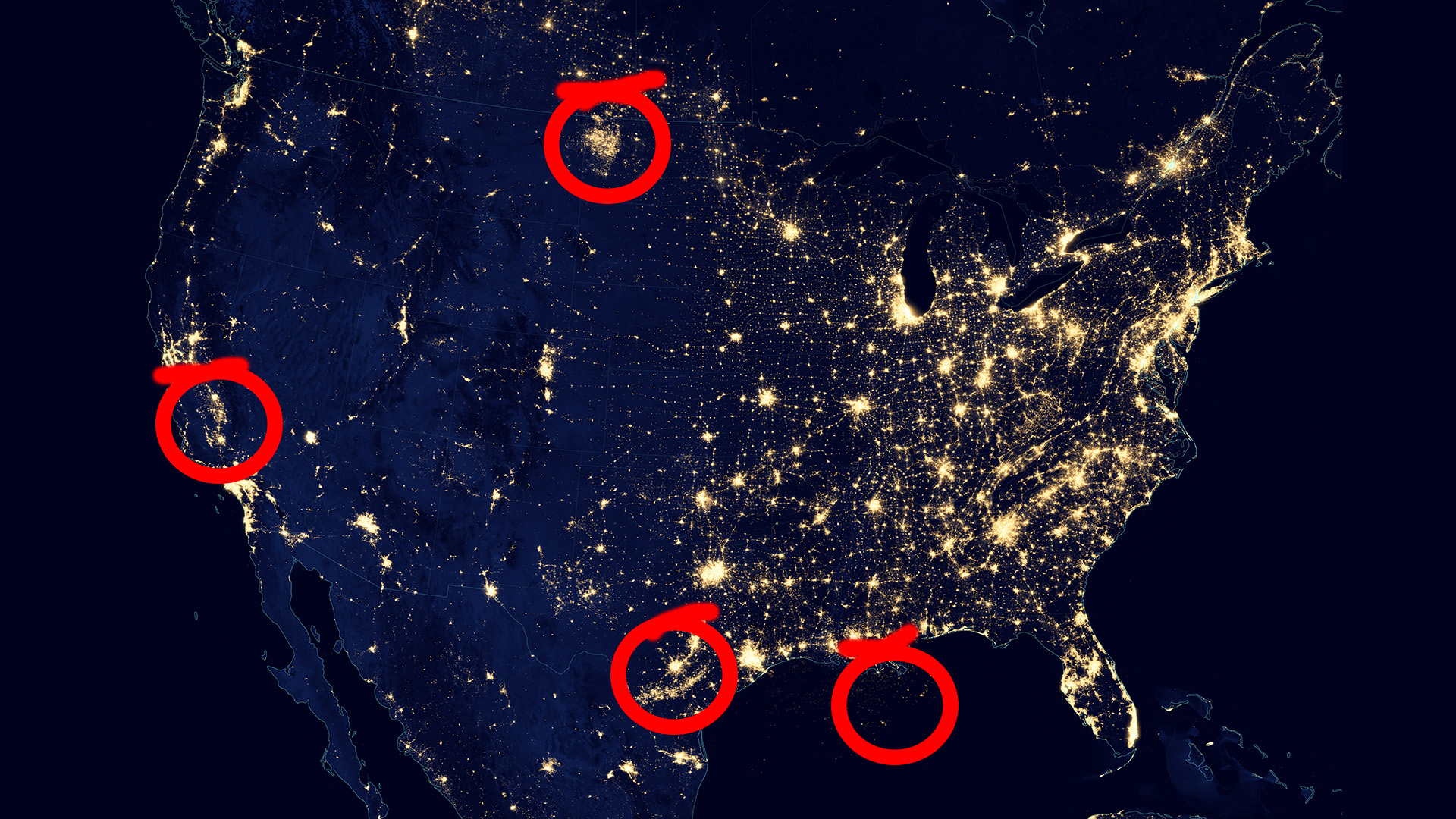

The Rio Grande, a meandering, flood-prone river, forms the border between Texas and Mexico, 1,254 miles from El Paso to the Gulf of Mexico. The final stretch, through what’s known as the Rio Grande Valley, already has 70 miles of “pedestrian barrier” — fences that stand 12 to 18 feet high and include various combinations of solid metal, metal mesh fencing and vertical steel slats or bollards.

Designed to stop people, these barriers also serve to stop most wildlife.

In addition to Southmost Preserve, pedestrian barriers also cross several state Wildlife Management Areas and portions of the South Texas National Wildlife Refuge Complex, which includes Lower Rio Grande Valley, Santa Ana and Laguna Atascosa refuges. The Audubon Society’s Sabal Palm Sanctuary, the other remaining stand of those native palms, ended up completely south of the wall. There the fence interferes with the natural spread of sabal palm seeds via the scat of animals such as coyotes, which are too large to pass through openings in the structure. The sanctuary also provides important habitat for ocelots, and biologists say the wall hampers critical genetic mixing of Texas and Mexico populations for this species.

People have different reasons for opposing the additional border walls proposed by the Trump administration, but in the valley, many of those reasons relate to an ecotourism industry that brings in $463 million annually. In the 1980s and 1990s, communities here worked hard to protect habitat in order to create that industry. Locals say more wall puts it at risk.

Najera points out that the wall and security infrastructure create noise, lights, traffic, surface disturbance, altered hydrology and, most seriously, habitat fragmentation.

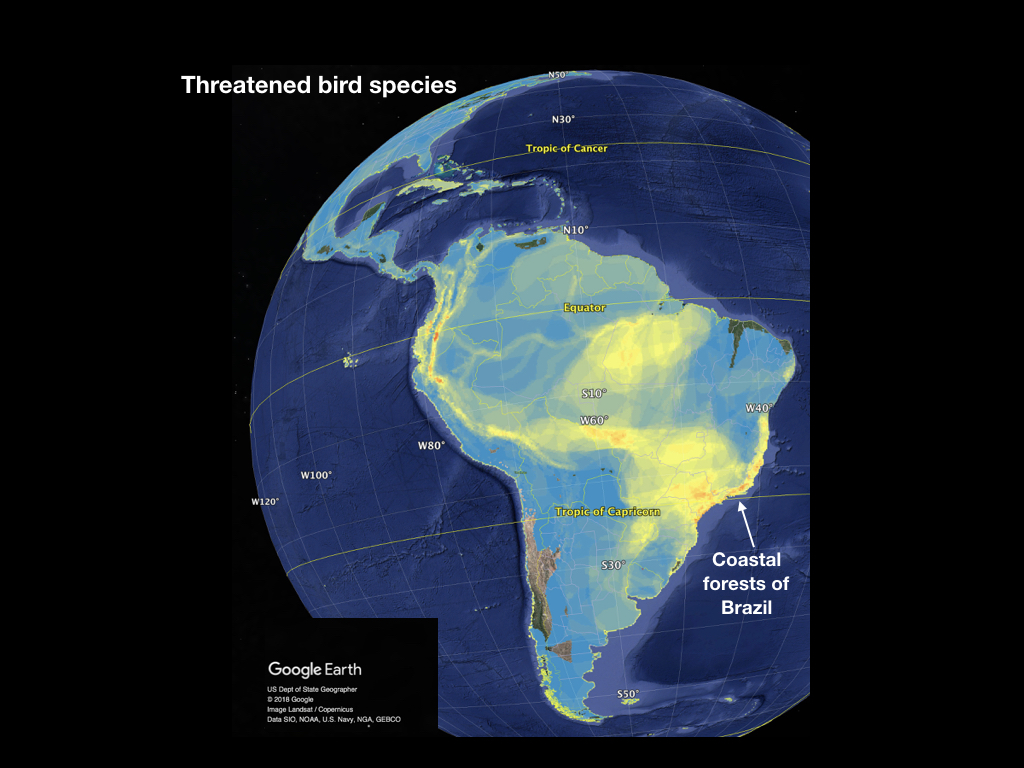

Breaking up species’ habitat limits their movement, says Tim Keitt, biology professor at the University of Texas, while also disrupting population connectivity and genetic interchange. Keitt is one of four scientists who reported, in the April 2018 journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, that every kilometer of new barrier proposed by the federal government represents the loss of at least 4.8 to 7.3 acres of habitat, not including construction sites, service roads or edge effects on adjacent land. A previous study Keitt co-authored concluded that new barriers along the border increased the number of species at risk, and other scientists have documented 841 vertebrate species alone that are at risk of extinction or severe decrease in numbers from proposed additional border wall segments.

“People fought very hard to preserve those last bits of habitat in the valley,” Keitt says. “It’s a very dynamic, growing area, agriculturally productive, and it was quite a battle to get these places preserved. It is tragic and a shame that those efforts could be compromised by shortsighted decisions.”

Keith Hackland, owner of Alamo Birding Services and the Alamo Inn, has worked against the idea of a border wall for 15 years. “If we want to preserve birds in the valley, we have to preserve the habitat they use, and to preserve the habitat, we need tourist dollars, which essentially place a value on the habitat,” he says. “Tourism is key.”

Hackland notes that existing sections of barrier have actually served to protect some habitat by moving migrant and Border Patrol activity to other areas. A continuous wall, however, would change those dynamics.

“Let’s say they build walls all along the Rio Grande levee in the Valley, but not at places like Santa Ana Wildlife Refuge and Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park. That would focus all the migrant and enforcement activity into those areas, which would ultimately degrade them.”

In addition to its effect on wildlife, the border wall degrades the experience of those who come to see wildlife. Last fall Hackland had clients cancel trips after reading news reports of bulldozers on the Santa Ana refuge and the nonprofit National Butterfly Center. This year’s spring birding season, fewer people stayed at his inn; he blames constant news coverage of violence along the border, which often fails to clarify that it happens on the other side.

“The wall is not what I want to see when I take people from Europe on a tour,” he says. “Aesthetically it demonstrates that our immigration policy is in tatters and not addressing what we need or what migrants need. It’s a way of diverting attention. It strikes people as strange that we were against the wall in Berlin but are building our own.”

As former project leader for the South Texas NWR Complex, Ken Merritt saw firsthand how the first round of border barrier affected wildlife. He also finds the wall unsightly. “It gives me a bad feeling about how we deal with our neighbors. I don’t think it’s particularly effective, and it’s not going to solve the problem.”

Merritt adds that he understands why some people in other parts of the country appreciate the idea of a wall. ”You can get a lot of notice by putting up a wall,” he says. “The folks who live in Iowa and watch Fox News think the problem is being solved, while very few people who live here and see how things work would agree.”

Placement of wall sections also can affect people’s access to protected areas, Keitt says. “Sabal Palms is a classic example. [Limiting access] would be quite tragic.”

Najera says visitors sometimes ask if they’re in Mexico after passing through the opening in the barrier into Southmost Preserve. “It is a mental, visual and physical barrier,” she says.

Hackland stresses that, so far at least, the valley remains one of the best destinations in the world for birders. “There isn’t another place in the world where you can see so many birds so close. It’s an unforgettable experience.”

Whether that remains true depends in part on whether wall proposals become reality.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

© 2018 Melissa Gaskill. All rights reserved.

Rios, who received the

Rios, who received the