Grant’s book Corrupted Science: Fraud, Ideology and Politics in Science is published today.

Just a few days after Donald J. Trump was elected President, we had dinner with Republican friends whom I’ll call Betty and Barney Rubble, because those are not their real names.

My wife and I were pretty numbed in dismay, so the conversation didn’t flow as freely as it normally would. We tried our hardest to stick to the traditional “don’t talk about politics” rule, but at the same time it was hard not to talk about what we viewed as the disaster that had been dealt to the environment — and, more personally, to the future lives of our daughter and her family, particularly our grandson Tom.

President-elect Trump had bragged on the campaign trail about how he was going to pull the United States out of the Paris Climate Accord, increase coal production and make the EPA “more industry-friendly.” Even were he to be booted from office within four years, reversing the consequences of such actions was going to take very much longer. People currently of Tom’s age, we explained, were going to pay a very steep price, and quite possibly with their lives, for the recent election result.

At first Betty and Barney couldn’t understand that we weren’t talking partisan politics — that it wasn’t because, so to speak, our football team had lost to their football team that we were so demoralized. “Tell you what,” said Betty at one point. “We didn’t much like your guy the last few years, either.” They didn’t much like Trump, come to that, but they couldn’t see what all the fuss was about.

Finally, though, they got it, recognizing the danger imminent to the environment.

Their response, however, astonished us. “We’ll all be dead and gone by the time it matters.”

They carried this dismissive attitude, despite the fact that they too have young relatives.

Back in the balmy days of 2006 or so, I was stung into action by the war on science being waged by the administration of the re-elected George W. Bush. I persuaded one of my regular publishers that I should write the book that, the following year, was published as Corrupted Science: Fraud, Ideology and Politics in Science. In it I talked about deliberate attempts to corrupt either science or the public understanding of science from the earliest days until what was then the present.

In the final, long section, I discussed the political corruption of science by national regimes. I focused on Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Soviet Union and George W. Bush’s America. (Despite spelling out very clearly in the text that I was in no way comparing Bush to Hitler and Stalin, I was immediately accused of doing exactly that by some critics. They then basked in the knowledge that they needn’t trouble to actually read the book.)

Corrupted Science did well, but of course it became dated. Some while later, the publisher closed its doors. The advent of Obama to the White House didn’t exactly solve the country’s science problems, but it did bring a huge improvement. The darkest days, I thought, were behind us.

Oh, boy, was I wrong.

When I suggested to the publisher at See Sharp Press that I’d like to revise and update Corrupted Science for the new era, he more or less took my hand off at the elbow in excitement.

When I suggested to the publisher at See Sharp Press that I’d like to revise and update Corrupted Science for the new era, he more or less took my hand off at the elbow in excitement.

Both of us expected that the new book would be modestly longer than the old. It would update the chapters on scientific fraud with more recent examples, add a discussion of predatory journals (which hadn’t been much of a thing back in 2007), look at the “replicability crisis,” expand the coverage of the antics of the Discovery Institute… and, of course, bring up to date the account of the mutilation of public science by America’s political leaders.

Again, I was wrong.

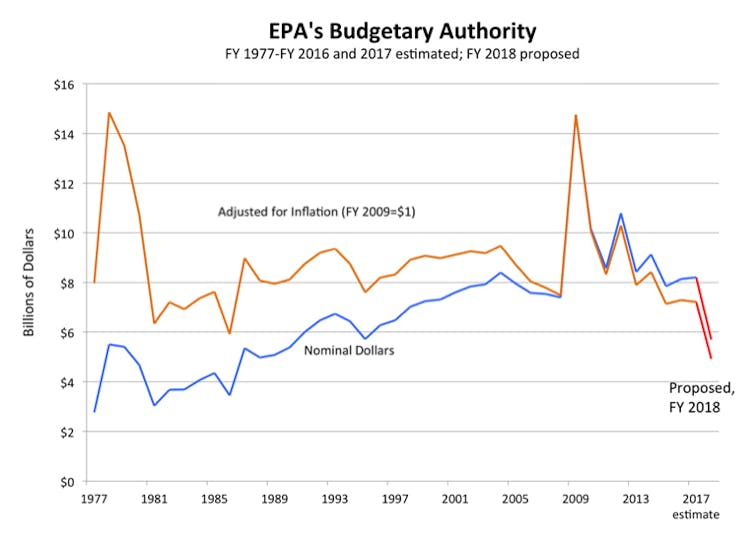

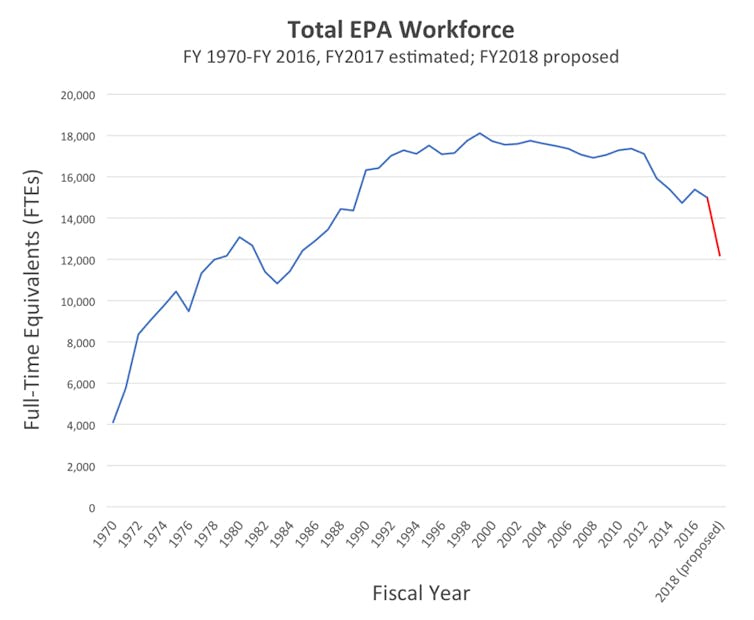

In the first place, I was wrong in my estimation of how much damage Donald Trump and his willing minion, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, would seek to do to American science, especially in terms of the environment. In fact, a major logistical problem for me while writing the book was that so much damage was being attempted in such a short period of time that it was well-nigh impossible for me to keep up with events. It seemed that each morning brought some new horror — often several — that demanded amendments to text I’d thought was just about ready to be put to bed.

My second error lay in thinking that the bulk of the updating of the later sections of the book would be about the Trump administration.

I soon realized that the anti-environmental and other anti-science actions were to a great extent just friend Betty’s maxim of “we’ll all be dead and gone by the time it matters” writ large.

Who cares if rising sea levels over the next few decades will exact a horrific human toll and deal devastating blows to the economy when there are profits to be made today? Who cares if many of our kids and grandkids will grow up intellectually stunted and psychologically crippled because of the lead and mercury they breathe and drink if doing anything about it now would affect the bottom line? Who cares if people starve as the seas die and the deserts expand?

It’s a cult of short-termism — tomorrow may just about matter, but what happens thereafter is someone else’s problem — and it permeates most corners of the Trump administration, including, of course, the Oval Office.

Where does this cult have its roots?

It’s easy enough to say that environmental short-termism has been a central platform of the Republican Party at least since Ronald Reagan tore Jimmy Carter’s solar panels from the White House roof and installed James Watt as Secretary of the Interior. (Chris Mooney’s excellent 2005 book The Republican War on Science will tell you all about this.)

But it’s actually, I think, more deeply rooted in U.S. culture. When Republican politicians pursue short-termist policies, it’s not because they regard them as especially good solutions to our ills. It’s because those policies happen to fit in with the short-termist aims of their paymasters.

The corporations.

Let’s consider those friendly folk at Big Sugar and Big Ag.

It’s only in the past few years that we’ve come more fully to recognize the damage that overconsumption of sugar does to us. We have an epidemic of obesity that has brought with it a spectrum of related diseases. Yet the evidence of sugar’s dangers has been there for decades, at least since the 1970s, when the British nutritionist John Yudkin demonstrated the connection beyond all possible doubt.

The reaction of the sugar industry was to destroy Yudkin’s reputation. With the assistance of scientists like Ancel Keys, large sugar corporations shrouded Yudkin’s work from view behind a smokescreen promoting the notion that unlimited sugar is good for you, sugar has no adverse effects on health and so on. There was even the claim at one point that sugar was innocent of causing dental cavities.

Industrialized livestock facilities, meanwhile, have been grossly abusing antibiotics. Companies employ the drugs to fatten animals faster and grow them in crowded environments where disease would otherwise be rife — or, at least, rifer than it is. The result is, as is at last now becoming widely known to Joe Public, that we’ve bred populations of bacteria — “superbugs” — that are resistant to antibiotics. Already some of the antibiotics we’ve been using as lifesavers in human medicine have become useless as a consequence of industrial agriculture’s greed and the demand of the American public for unsustainably cheap food. We’re looking at a very imminent post-antibiotic era, and it’s by no means clear how medicine is going to cope.

Public pressure has recently — far too recently — curtailed the abuse of antibiotics in livestock, and many major poultry producers now proudly boast that they forswear it. There are still outliers, though. As recently as January 2017, Sanderson Farms produced a document, “Supplemental Information Regarding Stockholder Proposal on Antibiotics,” which stated:

Numerous scientific studies have shown that the preventative use of antibiotics in food animals has not harmed human health, and that banning their use might actually be harmful to humans.

There are plenty of other examples of corporate entities and their representative associations lying about science, promoting bad science, burying good science, claiming that settled science is merely speculative, and otherwise muddying the public understanding of reality. Politicians of both major parties have served as useful idiots in this, and far too often as paid accomplices.

The asbestos industry pretended for decades that there was no link between their product and lung diseases, including cancer. (A climax came in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks when the George W. Bush administration and Mayor Rudi Giuliani pretended that the copious amounts of asbestos released in Manhattan were harmless, thereby causing the premature deaths of an untold number of emergency workers.)

For decades, the tobacco industry and its paid shills in the science community pretended the links between smoking and illness were not conclusively established. The chemicals industry formed a lynch mob against Rachel Carson and her efforts to alert us to the dangers of the overuse of pesticides; you can still find people online shrilling absurdly that she caused more deaths than Hitler or Stalin.

That same industry delayed international action when it was discovered that CFCs, used in industry, aerosol sprays and fridges, were the culprits in the formation and growth of the hole in the ozone layer. (And, as we’ve found out just within the past few weeks, despite the international ban on CFCs, it appears that somewhere in the world they’re being pumped out anyway.)

Oh, and did I mention how fossil-fuel companies have so effectively suppressed and corrupted the science on anthropogenic climate change? To this day, up to half the American public believe it’s unimportant, or a myth or even a “Chinese hoax.”

Which brings us back to Donald Trump and his determination to destroy environmental agencies — and the environment itself — in pursuit of short-term profits for industry.

In the longer term, of course, industry is going to have a hard time selling its products to people who’re dead.

But that’s too far in the future for Trump and the corporations that back him to take into account.

And so, to my surprise (and that of my fortunately very tolerant publisher), the new edition of Corrupted Science turned out to be nearly twice the size of the original. The bulk of the extra wordage being not so much about the anti-science activities of the Trump administration — although naturally they play an important part — as about those of the powerful corporate interests that have shaped those policies.

The two aspects are, of course, inextricably interwoven. If short-termist entities have essentially bought our government, then what else would you expect but that our government should promote short-termist policies about climate change, pollution, public lands and everything else?

But “we’ll all be dead and gone by the time it matters.”

Oh yeah?

© John Grant. All rights reserved.

The opinions expressed above are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

Last year Carter and Olivia, now 17 and 16, pointed their attention at one important solution for helping wildlife: getting people and businesses to reduce or phase out their use of disposable plastic, most notably straws, which have been known to injure or kill animals around the world.

Last year Carter and Olivia, now 17 and 16, pointed their attention at one important solution for helping wildlife: getting people and businesses to reduce or phase out their use of disposable plastic, most notably straws, which have been known to injure or kill animals around the world.