Dozens of important and potentially controversial decisions for the world’s most imperiled wildlife will come out of Geneva over the next few weeks.

That’s where the representatives from 183 nations will gather to discuss issues related to legal and illegal wildlife trade at the 18th triennial meeting of the member parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), a treaty aimed at regulating the commercial sale of threatened plants and wildlife.

CITES protects species by adding them to what’s known as its Appendices — listings of species that may or may not be traded. Species listed on Appendix I are banned from all international trade, while those on Appendix II may only be traded from proven sustainable populations. About 90 percent of CITES listings appear on Appendix II.

This year’s 12-day CITES meeting (Aug. 17-28), known as the Conference of the Parties, was originally scheduled for earlier this year in Sri Lanka but delayed due to violence in that country. The postponement didn’t diminish the meeting’s scope, though. The agenda includes a record 57 proposals affecting more than 550 highly traded species, ranging from megafauna such as elephants, rhinos and giraffes to less charismatic but lucratively traded species like sea cucumbers and rosewood trees.

This year’s 12-day CITES meeting (Aug. 17-28), known as the Conference of the Parties, was originally scheduled for earlier this year in Sri Lanka but delayed due to violence in that country. The postponement didn’t diminish the meeting’s scope, though. The agenda includes a record 57 proposals affecting more than 550 highly traded species, ranging from megafauna such as elephants, rhinos and giraffes to less charismatic but lucratively traded species like sea cucumbers and rosewood trees.

“CITES sets the rules for international trade in wild fauna and flora,” CITES Secretary General Ivonne Higuero said in a press release earlier this month. “It is a powerful tool for ensuring sustainability and responding to the rapid loss of biodiversity — often called the sixth extinction crisis — by preventing and reversing declines in wildlife populations. This year’s conference will focus on strengthening existing rules and standards while extending the benefits of the CITES regime to additional plants and animals threatened by human activity.”

Let’s take a look at five of the biggest issues on the table this year:

1. Rhinos and Elephants

Despite rampant, ongoing poaching threats, proposals this year could actually open up legal trade in elephants or rhinos.

Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe have proposed allowing legal trade in elephant ivory from their countries, as well as from South Africa, something that’s currently banned. Zimbabwe, meanwhile, wants to be allowed to sell live elephants to China.

These countries’ elephants are all currently listed under CITES Appendix II, while other nations’ elephants are listed in Appendix I. The four nations argue their elephant populations are healthy and can withstand international trade, but most experts argue that any legal ivory sale helps to spur demand for the products, which then inspires additional poaching and illegal trafficking. Experts also point out that African elephants frequently cross national borders, so they shouldn’t be considered the “national property” of any given country.

Meanwhile, a competing proposal would move elephants from these four nations to Appendix I, which would end the current “split listing,” restrict international trade and put all African elephants on the same level playing field.

We’ll have to wait and see which, if either, of these proposals gains traction. CITES itself recently published a report that found “poaching continues to threaten the long-term survival of the African elephant,” so the prospects of opening up trade again seem less than likely, but proponents of commercialization remain steadfast.

As for rhinos, eSwatini (formerly known as Swaziland) and Namibia want to open up trade for their southern white rhino populations, with the former wanting to sell rhino horns and the latter asking to sell both hunting trophies and live rhinos. South Africa also wants to increase trophy hunting of its black rhinos. Similar proposals were defeated at the last meeting three years ago, but commercial interests continue to push for legalization of the horn trade, something that’s likely to persist in the years ahead even if the proposals are again shot down this month.

2. Giraffes

The world’s tallest animals have undergone a shocking 40 percent population decline over the past few decades, and CITES will take up the issue for the first time this year. Thirty African states have submitted a proposal for restricting trade in giraffe hunting trophies, bones and hides under Appendix II.

The trophy hunting alone is a huge deal; according to the proposal, “the United States imported more than one giraffe hunting trophy a day” from 2006 to 2015. That’s more than 3,500 giraffes killed by American hunters over a single decade — the same period during which giraffe populations fell to fewer than 100,000.

Meanwhile we know the trade in most other giraffe products — such as the growing trade in giraffe-bone gun and knife handles — is extensive, but there are also huge data gaps concerning their country of origin or whether the specimens were legally or sustainably acquired. This reveals a need to place serious controls on this trade.

The disappearance of giraffes has often been referred to as a “silent extinction,” but the threats facing these iconic mammals have finally started to generate some noise. The fate of Africa’s giraffes may hinge on whether that’s now loud enough to generate support from a majority of voting parties this month.

3. Vaquita

A few weeks ago we heard that the population of critically endangered vaquita porpoises had fallen to fewer than 19 and possibly as low as six. Many conservation organizations now say it’s the last chance to save this species from extinction.

CITES can’t address the vaquita directly — there’s no trade in the animals — but in 2016 the parties to the treaty agreed to take on illegal trafficking of a fish from the same area called totoaba. Illegal gillnet fishing for totoaba — their swim bladders sell for big bucks in China — has been responsible for the deaths of dozens of vaquita over the past few years.

That agreement, sadly, didn’t lead to much, if any, action. Now, as Mexico prepares to allow commercial breeding of totoaba, conservation organizations (including the Center for Biological Diversity, publisher of The Revelator) have called for trade sanctions against Mexico to ensure more vaquita protective measures are put in place. They’re also calling for additional funding and other support to conserve both vaquita and totoaba in the wild and stronger law enforcement to address the illegal totoaba trade.

This may also serve as a reminder for Mexico and other countries to follow through on their promises to protect other imperiled species.

No matter what happens in Geneva this will be a critical year for the vaquita — and, we hope, not one that will end with the species’ extinction.

4. Exotic Pets

Hundreds of species commonly found in the legal and illegal pet trade will be up for discussion this year, including a wide range of lizards, iguanas, turtles, tortoises, frogs, newts and even spiders. Most would be added to Appendix II, but several proposals would place species — such as the highly trafficked Indian star tortoise — on Appendix I to end all legal international trade.

Perhaps the most interesting species on the pet-trade list is the spider-tailed horned viper from Iran, a huge, venomous snake known for using its tail to attract and kill birds. Trade in this species isn’t exactly rampant yet, but it’s turned up for sale recently on German social-networking sites. This measure would proactively try to control that trade before it gets any worse.

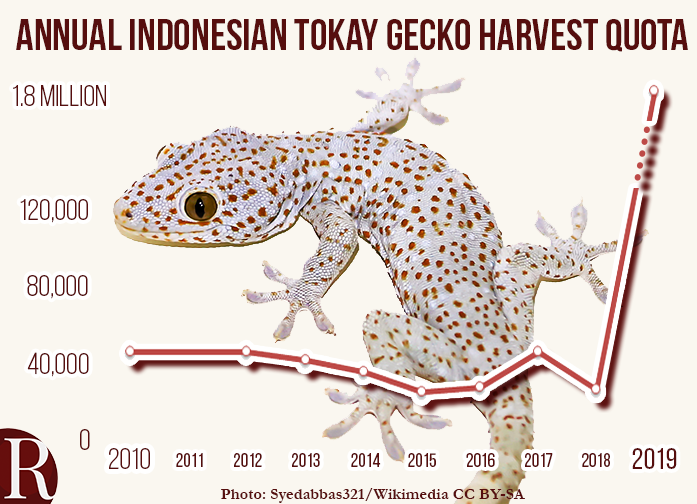

Of course, not all of these species are exclusively threatened by the pet trade. The tokay gecko, for example, is also highly traded for use in traditional medicine. That leads us to our next big topic.

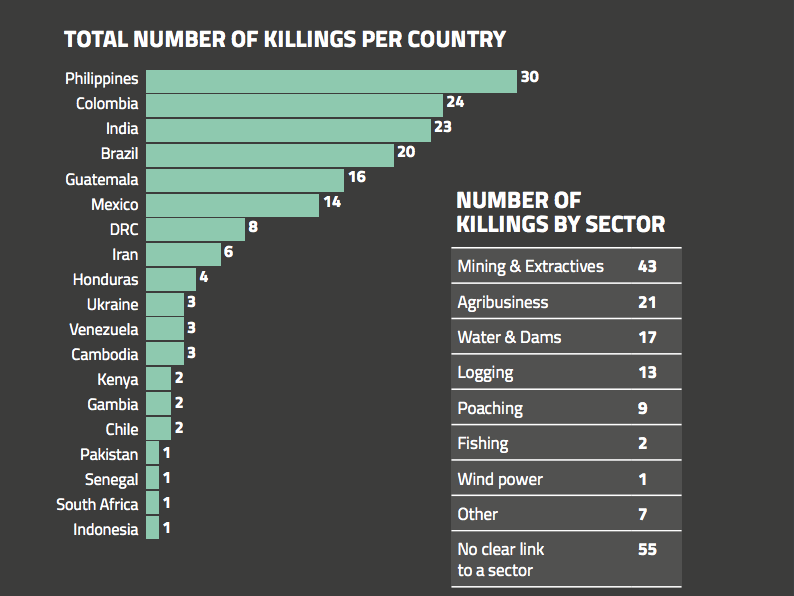

5. Wildlife Trafficking

CITES will have an active agenda related to illegal wildlife trafficking this year, with key discussions on songbirds, big cats (especially China’s large number of tiger farms), coral, hawksbill turtles, saiga antelopes, rosewood and other species. Even woolly mammoths are on the list. (Yes, sometimes extinct species require protective trade restrictions. In this case ivory from recently killed elephants is sometimes disguised or laundered as mammoth ivory, a trade that could be curtailed by a proposal to add mammoths to Appendix II.)

In addition to species-specific proposals, the participants at this year’s CITES meeting will also discuss building international capacity to track and address the multibillion-dollar wildlife crime industry — a problem so pervasive that some experts say it may require an entirely separate convention. They’re also expected to discuss Vietnam’s role as both a consumer country and a hub for transit of wildlife parts, improving the livelihoods of rural communities, tactics to address wildlife cybercrime, and what to do with confiscated products from species such as pangolins, rhinos and rosewoods.

And on top of all that, the CITES parties will also discuss their strategy for the year 2020 and beyond. With biodiversity around the world in crisis and hundreds of thousands of species at risk of extinction, that may end up being the biggest topic of all.

![]()

Captive vs. Wild

Captive vs. Wild

More than 130 years later, a new paper examines the genetics and morphology of speckled skinks from around New Zealand and comes up with a surprising conclusion: They’re actually at least six different species, one of which — ironically enough, the one first identified by Boulenger — may now be extinct.

More than 130 years later, a new paper examines the genetics and morphology of speckled skinks from around New Zealand and comes up with a surprising conclusion: They’re actually at least six different species, one of which — ironically enough, the one first identified by Boulenger — may now be extinct.