Can the United States make progress on its food-waste problems? Cities like San Francisco — and a growing list of actions by the federal government — show that it’s possible.

San Francisco passed the nation’s first mandatory composting law a little over 10 years ago, requiring residents and businesses to separate food waste for municipal trash collection. The city, which already had an enormously successful recycling program, incentivized composting through consumer education, a scalable fee structure and, as a last resort, penalties. It also streamlined its entire waste collection system by contracting with a single waste hauler. That company, in turn, now delivers food waste to a composting facility that converts it to rich fertilizer, which is sold to California’s vineyards and farms at a profit.

The result? Composting has helped San Francisco reduce its annual waste by a whopping 80%, taken pressure off local landfills, and reduced the city’s greenhouse gas emissions. And the city is now a global leader in municipal-waste reduction.

San Francisco’s success has inspired other local governments to take similar action. In recent years a dozen other cities and states have adopted their own mandatory composting laws. Although it’s still a growing movement nationally, experts say this composting shift represents an important way that the United States can tackle food waste.

Every year American consumers and businesses waste hundreds of millions of pounds of food. The EPA estimates that about 22% of the foods we produce end up in landfills, with another 22% burned for energy. This contributes to climate change and a host of other environmental and humanitarian issues.

Congress agrees on the national value of community composting as one element of solving this problem. The 2018 Farm Bill, which passed a little over a year ago, created a fund for new composting programs.

It was one part of an unprecedented suite of actions in the Farm Bill designed to curb U.S. food waste. The actions encourage systemic change in the country’s food system and support an ambitious government goal to slash domestic food waste by half in the next decade.

The Obama administration established that goal in 2015, and it continues today under the Trump administration. It mirrors a United Nations goal to halve food waste globally by 2030.

In the United States, the broader effort is spearheaded by the EPA and the Department of Agriculture. With help from the Farm Bill, the country now seems poised to bring about meaningful change.

However, experts caution that continued progress will depend on continued support from Congress and solid commitments from industry, government, nonprofits and even consumers.

The Promise of Reducing Waste

No matter which way you slice it, food waste is a significant issue. In the United States, up to 40% of all food is tossed in the garbage. It’s more than just the uneaten food you scrape off your plate. Food waste happens at every stage of production, from vegetables rotting on the vine to dumpsters full of unsold fruit and meat at your local grocery store.

“Our food system is operating with a 40% inefficiency,” says Katy Franklin, operations director for the nonprofit ReFED, a leading resource for food-waste research, data and solutions design. The organization works in support of both U.S. and UN waste goals.

It comes with a huge cost for the climate: This waste represents an enormous use of fossil fuel to grow, ship and refrigerate food that no one will ever eat. And as food products decompose, they release methane, a greenhouse gas with many times the heat-trapping potential of carbon dioxide. Nearly all discarded food in the U.S. ends up in landfills, where it produces up to 14% of our country’s methane emissions.

Looking at production, distribution and disposal, the United Nations estimates that excess wasted food generates a full 8% of worldwide global carbon emissions.

If food waste were a country, it would be the world’s third-largest greenhouse gas emitter after China and the United States.

And the waste contributes to a host of other problems, including deforestation, pollution from fertilizers and pesticides, and human-rights issues from forced labor or food inequality.

But recognizing that problem also creates the opportunities for improvement. Tackling food waste, Franklin points out, “can be a huge part of reducing greenhouse gas emissions” and solving other problems.

Franklin and others see a lot of reasons for optimism, especially the 2018 Farm Bill, the most important elements of which are just starting to take effect. Top food-waste experts at ReFED and the Harvard Law School’s Food Law and Policy Clinic collaborated on recommendations for the bill, which were mostly accepted by Congress.

“It was satisfying and really thrilling to see the bill provide both funding and intellectual investment in the issue,” says Franklin. “That’s a magical combination.”

The Farm Bill Creates Leadership

While the Farm Bill put a range of programs in motion, three specific elements showcase the systemic changes needed to achieve serious cuts in food waste.

First, the law set the stage for the creation of a high-level “food-waste liaison” under the Secretary of Agriculture, with specific duties for researching and cutting waste. Franklin calls the new position an exciting signal of government leadership, which can help galvanize participation throughout the business, consumer and government sectors. While the 2018 Farm Bill did not pay for this new position, preliminary funding was included in the 2020 appropriations bill that passed in December 2019. The provision was inserted in both bills by Rep. Chellie Pingree (D-Maine), who in 2018 also launched Congress’ first-ever Bipartisan Food Recovery Caucus and has introduced other bills to curb food waste.

Until the liaison is hired, many of the duties assigned to the position by the Farm Bill fall to Elise Golan, the USDA’s director for sustainable development. She describes the role as a natural fit for USDA because reducing food waste addresses the department’s focus areas, including agriculture, nutrition, food safety and the environment.

Golan’s office is presently determining the best methods to define and measure U.S. food waste, an early task the Farm Bill laid out for the liaison.

“We need benchmarks to generate good statistics,” she says, “but even more importantly they help us identify the drivers of waste at every level, from farms to consumers.”

Although some broad national estimates exist, experts say a lack of more specific data limits the ability to track progress in reducing waste across the entire food system. A 2019 Government Accountability Office report reached similar conclusions. The report identified specific data gaps and pointed to inconsistent methods for measuring food waste among government agencies and others as a barrier to progress.

Golan says part of solving that problem requires greater coordination among federal agencies, another liaison role described by the Farm Bill. As an example of headway toward the goal, she points to an interagency strategy signed in 2019 by EPA, USDA and the Food and Drug Administration, which includes a commitment to improving food-waste measurement.

Other roles the liaison may eventually take on, as dictated in the Farm Bill, include raising public awareness, expanding existing programs, and nurturing both governmental and non-governmental partnerships, broad roles that experts say are best served by federal leadership.

Feeding the Hungry

In the second effort at establishing systemic change, the Farm Bill set the stage for removing hurdles that commonly prevent supermarkets, restaurants and farmers from donating unwanted food to charity.

According to the nonprofit Feeding America and other experts, food donations carry enormous potential for reducing waste while helping people in need. But getting companies to donate goods has been a problem. Surveys have shown that many retailers avoid donating surplus food because they fear potential lawsuits over less-than-optimal foodstuffs, even though they’d theoretically be protected by so-called “good Samaritan” laws.

The Farm Bill took steps to fix that problem by clarifying protections established more than two decades ago under the 1996 Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act. The Act previously offered liability to individual donors, nonprofits and “gleaners” — people who gather excess food left behind on agricultural fields. The new bill expanded that liability protection to cover direct donations by retailers.

The Farm Bill also required whoever eventually takes on the food-waste liaison role to publish additional guidance on the Bill Emerson Act, something no agency has done in the decades since the law’s passage.

Experts say weeding out this confusion around liability protections can spur growth in commercial food donations. Toward that end, the Farm Bill also authorizes millions of dollars to help farmers participate in donation programs, especially for the perishables that comprise a high percentage of U.S. food waste. As one of the first examples, this September the USDA rolled out a new program that reimburses farmers for milk donated to low-income families.

More Composting

The third example from the Farm Bill is a new fund to support community composting programs, which provides a total of $25 million to jumpstart pilot efforts in at least ten states.

Franklin and others call this provision especially important.

“There are so many valuable components of food-waste material,” says Franklin. “There’s really no reason they shouldn’t be part of a circular economy that helps produce energy, soil and other products.”

That’s just what San Francisco’s mandatory composting law has done, while also alleviating the burden on landfills and sharply cutting heat-trapping methane emissions.

There’s an economic benefit, too, says Franklin. Recycling food often creates more jobs than tossing it. That point holds true in Massachusetts, where recycling food waste supported over 900 jobs and $175 million in economic activity in 2016 alone, according to a recent report from the state government.

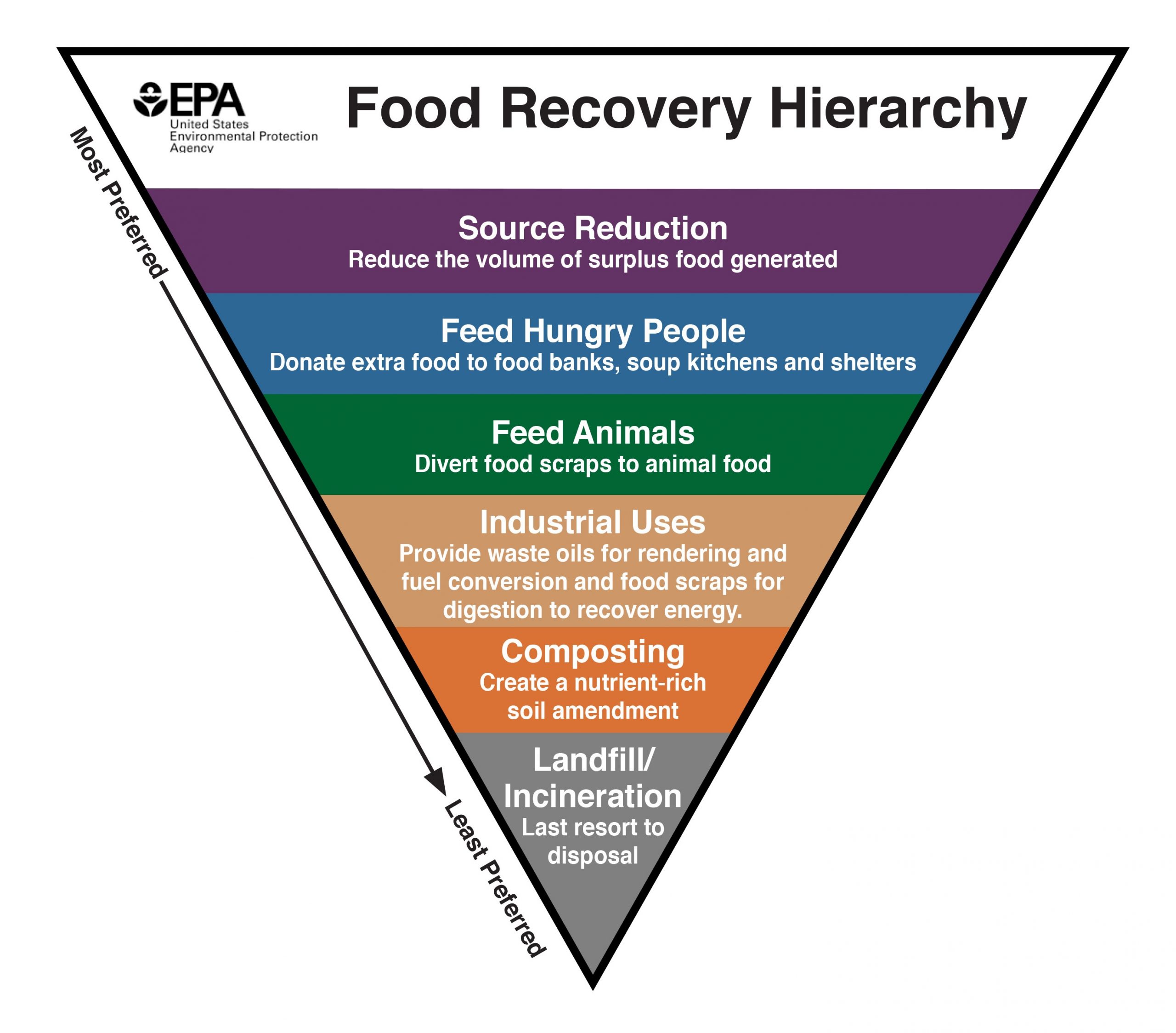

The three Farm Bill examples track well with a “food recovery hierarchy” developed by the EPA and others to guide thinking on food waste. It emphasizes that communities address waste prevention as their top priority, then move through a series of other solutions that include donating, repurposing and composting food, all before the least desirable practice of dumping it in a landfill.

Beyond the Farm Bill

Congress and government agencies are far from the only ones working on food waste. If anything, they’re late arrivals in a field where conservation and humanitarian groups have been toiling for years. They include the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), ReFED, Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, Feeding America and many others, as well as hundreds of local food rescue groups that connect unwanted food with people in need. In fact, the Farm Bill provisions reflect many of these organizations’ longstanding recommendations.

The groups have helped spur the food industry into action. For example, large retailers such as Walmart began efforts to standardize food expiration labels after a 2013 report by NRDC and the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic showed confusion over the labels leads up to 90% of Americans to toss perfectly good food. In 2017 they were joined by industry associations representing dozens of major firms, who volunteered to trim the more than ten date labels — including “best by,” “sell by,” and “expires on” — to just two: “best if used by” and “use by.”

The Food and Drug Administration approved their choice of “best if used by” to indicate optimal quality this past May but stopped short of sanctioning “use by” as a marker for when an item could be safely consumed.

Still, ReFED and others point out that voluntary industry efforts are not enough. They say a continuing mishmash of retailer approaches and state food safety laws have prevented the universal standardization of labels. That standardization, they say, is only achievable by federal legislation that includes oversight, comprehensive consumer education, and consistency between state and federal laws. That may still emerge: In 2019 Rep. Pingree of Maine introduced label reform legislation that matches ReFED’s recommendations.

But as label reform shows, major industry players are coming to the table to help fight food waste. The EPA and USDA encourage their efforts through the 2030 Food Waste Champions program, which highlights companies working toward the government’s 2030 goal. Members include Walmart, Campbells, Kellogg, Kroger and more than 20 other large retailers. Although the program is voluntary and doesn’t require independent verification, highlighting again the need for better overall measurement standards, supporters argue it incentivizes companies to reduce waste.

“We’ve been lucky,” says Franklin, “because reducing food waste has a lot of appeal among businesses right now.”

But as Franklin says, unexpected events or market shifts could temper efforts at any time. She also points to the need for greater consumer education, as she’s regularly reminded that most people remain unaware of the food-waste problem.

But she sees promising work there, too, and highlights the World Wildlife Fund’s Food Waste Warrior toolkit for school teachers. Similar experiential education is also included in a bill Rep. Pingree and others introduced in January, which would initiate a new federally supported food-waste program in schools.

Taken together, all of these examples show legislators, agencies, nonprofits and industry collaborating to tackle food waste, with growing coordination around the government’s 2030 goal. Experts say such coordination is necessary for solving America’s — and the world’s — food-waste problem.

Ultimately consumer behaviors also need to change, but once again we can look to San Francisco for proof that this can work. Once the city government and industry put in place tools and incentives, consumer behaviors followed.

Franklin calls it a matter of fitting all the puzzle pieces together — and it’s almost like assembling a recipe to reduce food waste.

Experts agree we’re still a long way from meeting our 2030 goal, and caution that the years ahead will show if continued coordination and investment keep us moving forward, but they also say the hunger for solutions is another sign of progress.

Resources:

![]()

Of course, the annual presidential budget is more spectacle than anything else. The real budget each year comes from Congress, which may or may not take up the president’s suggestions.

Of course, the annual presidential budget is more spectacle than anything else. The real budget each year comes from Congress, which may or may not take up the president’s suggestions.

This gruesome scene has played out several times in Argentina in recent years. In one incident that made worldwide headlines,

This gruesome scene has played out several times in Argentina in recent years. In one incident that made worldwide headlines,

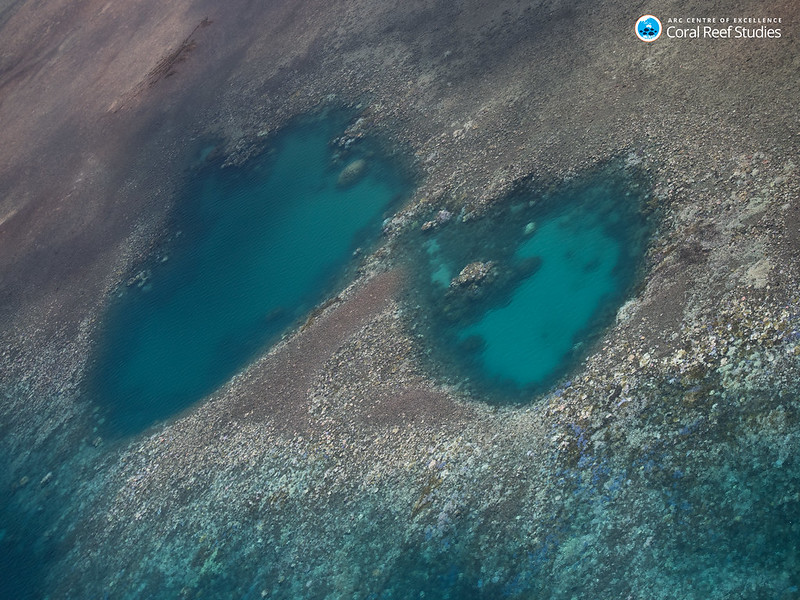

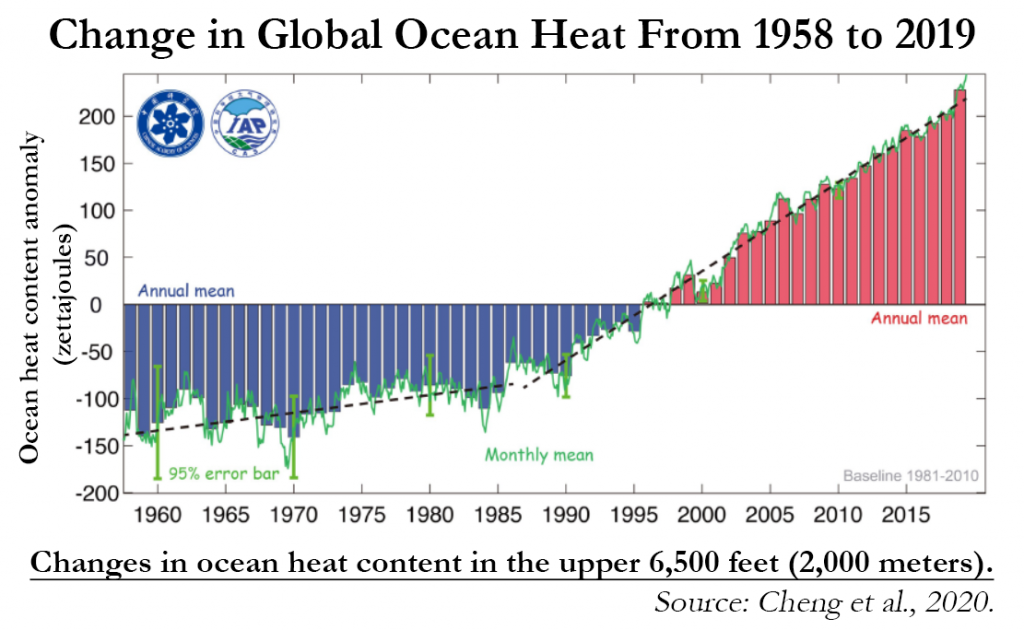

“Every year the ocean waters get warmer, and the reason is because of the heat-trapping gases that humans have emitted into the atmosphere,” says

“Every year the ocean waters get warmer, and the reason is because of the heat-trapping gases that humans have emitted into the atmosphere,” says