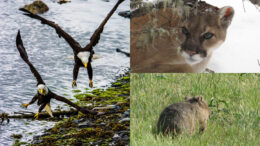

Easily confused with the larger Canada lynx, the bobcat is a close relative. In fact they’re known to hybridize at the southern extent of lynx range, where the two species overlap. Two subspecies of bobcat — the western and eastern, as supported by current science — live in North America. Across its range, the bobcat is subject to significant hunting and trapping for its fur and recreation that can threaten populations.

Easily confused with the larger Canada lynx, the bobcat is a close relative. In fact they’re known to hybridize at the southern extent of lynx range, where the two species overlap. Two subspecies of bobcat — the western and eastern, as supported by current science — live in North America. Across its range, the bobcat is subject to significant hunting and trapping for its fur and recreation that can threaten populations.

Species name:

Lynx rufus

Description:

Short and stocky, bobcats have dense facial ruffs and are known for their “bobbed” tails and pointed ear tufts, although the latter is often absent or short. While bobcats are much smaller than cougars or mountain lions, they’re considered medium-sized wild cats. Weighing between 8 and 40 pounds and reaching 49 inches long, bobcats are often two to three times the size of house cats.

Where it’s found:

The bobcat is widespread across North America, with a range extending from southern Canada through the contiguous United States into southern Mexico to the state of Oaxaca.

IUCN Red List status:

Major threats:

Bobcats are widely exploited for their pelts, which primarily support international markets for spotted furs. Volatile fur markets can lead to unpredictable harvesting, making management of the species difficult and at times impossible.

The species is also killed for livestock depredation, both perceived and real.

In some places coyotes and domestic animals have reduced bobcat populations. Rodenticide poisons, which bobcats ingest with their prey, are also a significant threat in parts of the West.

Notable conservation programs:

Panthera director Wai-Ming Wong and I collaborate with researcher Kim Sager-Fradkin of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe on the Olympic Bobcat Project. Together we completed a collaborative camera trapping season across a grid of 180 cameras in collaboration with the Lower Elwha Klallam, Port Gamble S’Klallam and Jamestown S’Klallam Tribes. We categorized 500,000 images and organized them to train a machine-learning classifier (PantheraIDS), which when complete will be able to identify the animal in camera trap images at a rate of 1,000 images per minute, with an approximately 96%-98% success rate. This tool will be shared with First Nation collaborators to help them build capacity and monitoring tools, as they double the size of their sampling to encompass all sides of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state.

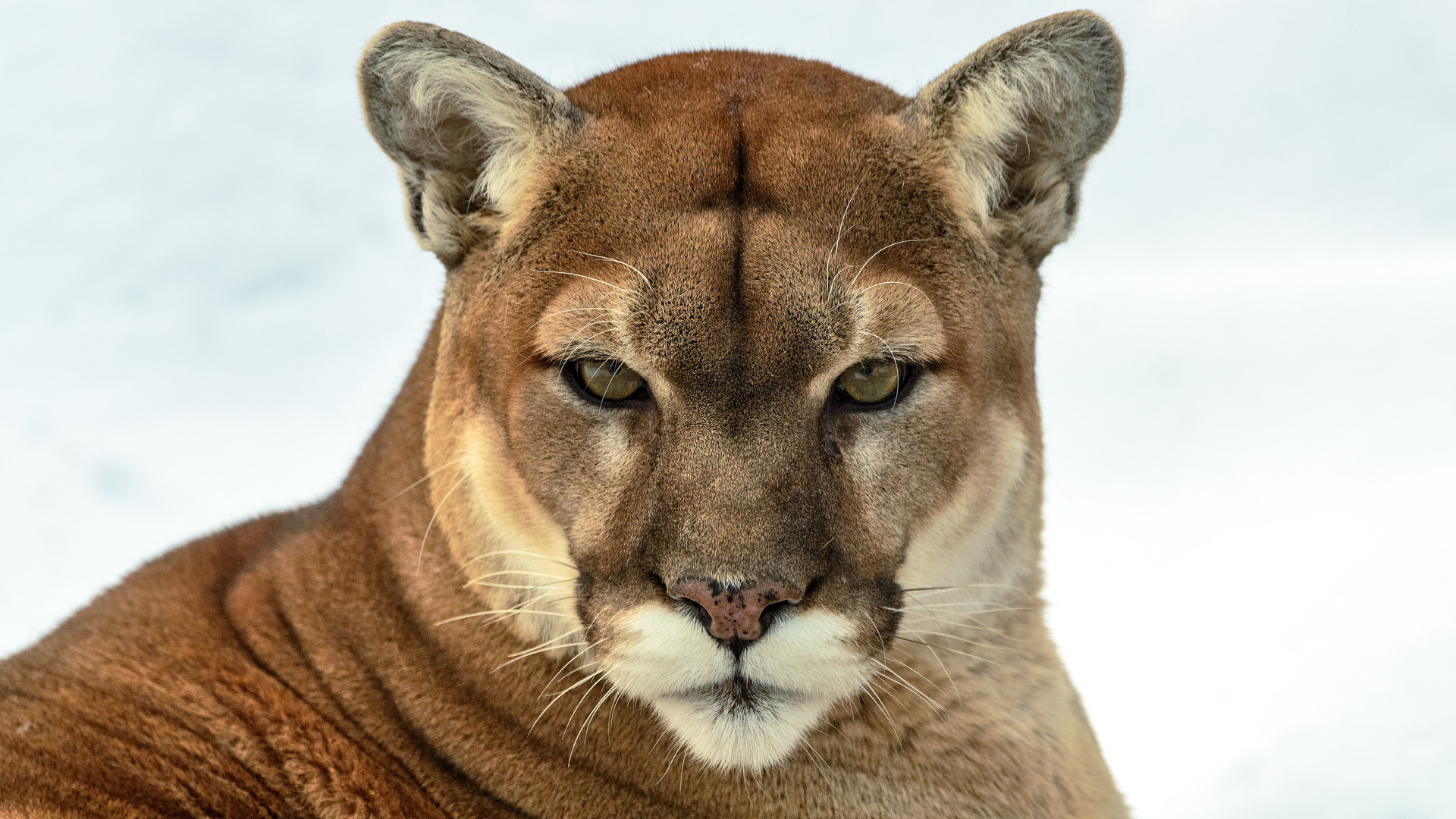

A bobcat feeds at a kill made by a mountain lion in Washington state.

In partnership with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, Panthera is currently investigating puma-bobcat competition and coexistence on the Olympic Peninsula, as well as their economic benefits to people, including controlling rodents that affect timber production. John Livaitis at the University of New Hampshire and Clay Nielsen at the Southern Illinois University are among the veteran bobcat ecology researchers; Seth Riley and Laurel Serieys are among those contributing studies on the impacts of habitat fragmentation, rat poisons and disease on California’s bobcats.

The latest member of Panthera’s Global Alliance for Wild Cats — Jon Ayers — has just pledged $20 million over 10 years to wild cat conservation, with a focus on smaller cats. This represents the largest-ever commitment to small cat conservation in the world.

What else to we need to understand to protect these species?

Occasionally news reports surface of bobcat attacks on people, including a recent incident in North Carolina. As I explain here, such encounters are very much out of the ordinary and involve unique circumstances. Bobcats are not to be feared but instead admired for their beauty and critical contribution to maintaining healthy ecosystems benefiting our survival.

My favorite experience:

I once witnessed a bobcat kill a goose. The bobcat was so small and the goose so large that it had to walk slowly, straddling the bird between its legs. The bobcat was so consumed with its task of retreating into nearby woods that I was able to accompany it on this journey. We walked together perhaps five long minutes, the carcass dragging a trail through the duff, before the bobcat seemed to suddenly become aware of my presence. He dropped the bird, stared at me in shock for a moment, and then bounded away without a backward glance.

I assume he returned, though: When I checked on the site an hour later, the goose was gone.

Key research:

-

- Kitchener, A. C. et al. (2017). A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group. Cat News 11: 38–40.

- Fedriani, J. M.; Fuller, T. K.; Sauvajot R. M. & York, E. C. (2000). “Competition and intraguild predation among three sympatric carnivores”. Oecologia. 125 (2): 258–270.

- Serieys LEK, MS Rogan, SS Matsushima, CC Wilmers. 2021. Road-crossings, vegetative cover, land use and poisons interact to influence corridor effectiveness. Biological Conservation, 253:

- Serieys LEK, Lea AJ, Epeldegui M, Armenta TC, Moriarty J, VandeWoude S, Carver S, Foley J, Wayne RK, Riley SPD, & Uittenbogaart CH (2018). Urbanization and anticoagulant poisons promote immune dysfunction in bobcats. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1871), 20172533.

![]()

Yeah. It’s funny because these “weird plants” — I sometimes feel like they almost sort of wrote themselves in a weird way. I didn’t set out to do it in that way, but I started a collection of paintings on these particularly strange plants. And then they suddenly made sense to me to fall into these groups — i.e., the “killers” and the “vampires” — and they started to take on almost characters and roles. And it was easy to tell stories about these plants, all the while explaining the science.

Yeah. It’s funny because these “weird plants” — I sometimes feel like they almost sort of wrote themselves in a weird way. I didn’t set out to do it in that way, but I started a collection of paintings on these particularly strange plants. And then they suddenly made sense to me to fall into these groups — i.e., the “killers” and the “vampires” — and they started to take on almost characters and roles. And it was easy to tell stories about these plants, all the while explaining the science.

In Austin, where I live, winter dips below freezing once every 10 years. This time the temperature plunged not just below freezing but into the single digits. And there it sat, not just overnight or two, but for five long days.

In Austin, where I live, winter dips below freezing once every 10 years. This time the temperature plunged not just below freezing but into the single digits. And there it sat, not just overnight or two, but for five long days.

During that time, residents of the Kenai Peninsula and nearby Anchorage battled suffocating smoke. Roads and trails were closed. And some communities were told to prepare for evacuations.

During that time, residents of the Kenai Peninsula and nearby Anchorage battled suffocating smoke. Roads and trails were closed. And some communities were told to prepare for evacuations.

The Maine Event: The Pine Tree State made innovative progress on three critical environmental issues recently. First, Maine required its pension system and state treasury to

The Maine Event: The Pine Tree State made innovative progress on three critical environmental issues recently. First, Maine required its pension system and state treasury to