This story is part of “Climate Crimes,” a special series by The Guardian and Covering Climate Now focused on investigating how the fossil fuel industry contributed to the climate crisis and lied to the American public.

This story is part of “Climate Crimes,” a special series by The Guardian and Covering Climate Now focused on investigating how the fossil fuel industry contributed to the climate crisis and lied to the American public.

The oil and gas industry wants to play a word-and-picture association game with you. Think of four images: a brightly colored backpack stuffed with pencils, a smiling teacher with a tablet tucked under her arm, a pair of glasses resting on a stack of pastel notebooks, and a gleaming school bus welcoming a young student aboard.

“What do all of these have in common?” an April 6 Facebook post by the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association (NMOGA), asked. “They are powered by oil and natural gas!”

Here in New Mexico — the fastest-warming and most water-stressed state in the continental United States, where wildfires have recently devoured over 120,000 acres and remain uncontained — the oil and gas industry is coming out in force to deepen the region’s dependence on fossil fuels. Their latest tactic: to position oil and gas as a patron saint of education. Powerful interest groups have deployed a months-long campaign to depict schools and children’s wellbeing as under threat if government officials infringe upon fossil fuel production.

In a video spot exemplary of this strategy, Ashley Niman, a fourth grade teacher at Enchanted Hills elementary school, tells viewers that the industry is what enables her to do her job.

“Without oil and gas, we would not have the resources to provide an exemplary education for our students,” she says. “The partnership we have with the oil and gas industry makes me a better teacher.”

The video, from September of last year, is part of a PR campaign by NMOGA called “Safer and Stronger.” It’s one of many similar strategies The Guardian tracked across social media, television and audio formats that employs a rhetorical strategy social scientists refer to as the “fossil fuel savior frame.”

“What NMOGA and the oil and gas industry are saying is that we hold New Mexico’s public education system hostage to our profit-motivated interests,” said Erik Schlenker-Goodrich, executive director of the Western Environmental Law Center. “There’s an implied threat there.”

Last year New Mexico brought in $1.1 billion from mineral leasing on federal lands — more than any other state. But the tides may be turning for the fossil fuel industry as officials grapple with the need to halve greenhouse gas emissions this decade. Prior to mid-April, the Biden administration had paused all new oil and gas leasing and the number of drilling permits on public lands plummeted.

In response, pro-industry groups are pushing out what some experts have called “sky is falling” messaging that generates the impression that without oil and gas revenue, the state’s education system is on a chopping block. (NMOGA did not respond for comment).

Since February NMOGA has flooded its social media pages with school-related motifs like buses and books, but also with images of empty, abandoned classrooms accompanied by reminders about how the state’s schools “rely on oil and gas production on federal land for more than $700 million in funding.”

Elected officials have parroted this framing.

“This is a matter of critical importance to all, but especially to New Mexico’s schoolchildren, who have suffered greatly during the pandemic,” state representative Yvette Herrell co-wrote in the Santa Fe New Mexican in February.

But tax, budget and public education funding experts say linking the federal leasing pause to a grave, immediate risk to public education is deceptive.

“Any slight reductions stemming from pauses or other so-called ‘adverse’ actions would have zero immediate effect on school funding overall, much less whether students get the services they need to recover from the ill effects on their learning from the pandemic,” said Charles Goodmacher, former government and media relations director at the National Education Association, now a consultant. The sale of leases does not lead to immediate drilling, he said. Often, companies sit on leases for months or years before production occurs.

And as it happens, New Mexico currently has a budget surplus from record production.

Industry attempts to convince New Mexicans that the state’s public education system is wholly dependent on oil and gas are based on a tough truth: decades of steep tax cuts have indeed positioned fossil fuels as the thunder behind Democratic-led New Mexico’s economy. In 2021, 15% of the state’s general fund came from royalties, rents and other fees that the Department of Interior collects from mineral extraction on federal lands. Oil and gas activity across federal, state and private lands contributes around a third of the state’s general fund of $7.2 billion, as well as a third of its education budget.

Commissioner of public lands Stephanie Garcia Richard, herself a former classroom teacher, has been at the forefront of efforts to diversify the New Mexican economy since she was elected to manage the state’s 13 million acres of public lands in 2018.

“When I ran, in my first campaign, we talked a lot about how a schoolteacher really understands what every dime that this office makes means to a classroom.”

Garcia Richard takes pride in being the first woman, Latina and teacher to have been elected to head the office, which oversees around $1 billion in revenue generation each year. Since 2019 she’s launched a renewable energy office and outdoor recreation office to raise money from those activities, though Garcia Richard doesn’t believe that money will ever fully make up for oil and gas revenue. “I don’t want anybody ever to think that I have some notion that the revenue diversification strategies we’re pursuing right now somehow make a billion dollars.”

New Mexico attorney general Hector Balderas, a Democrat, is another top state official charged with managing the state’s energy and economic transition.

Given the same geographic features that make New Mexico the “land of enchantment,” the state is positioned to become a national leader in solar energy, Balderas said. But four of the state’s major solar farms are severely behind schedule.

Balderas, who has accepted $49,900 in campaign contributions from oil and gas over seven election cycles, said that a sudden disruption in new oil and gas leasing — such as the blanket moratorium the Biden administration originally proposed in January last year — would have an outsized impact on New Mexico’s most vulnerable.

“You would cut out nearly a third of the revenue that we rely on to fund our schools and our roads and our law enforcement community,” he said. “I don’t think environmental activists really think about that perspective: How progressives have cleaner air but then thrust original Americans like Native American pueblos into further economic poverty.”

Some on the receiving end of oil and gas revenue stress that not all educators and students embrace fossil fuel industry money in public schools. Mary Bissell is an algebra teacher at Cleveland high school in Rio Rancho, who cosigned a letter in November, along with more than 200 educators, asking NMOGA to “stop using New Mexico’s teachers and kids as excuses for more oil and gas development.”

Bissell says in spite of how cash-strapped schools may be, many of her colleagues don’t want oil and gas money.

“I’m not going to teach my kids how to find slope based on fracking,” she said of her math courses. Bissel characterized NMOGA’s attempt to portray educators as a unified force beholden to oil and gas funding as “disgusting.”

In some states, including Rhode Island and Massachusetts, state attorneys general have taken it upon themselves, as the leading law enforcement and consumer protection officials, to sue oil and gas companies for deceiving consumers and investors about climate change through their marketing. Balderas’s office said it is not actively pursuing that strategy at this time.

Seneca Johnson, 20, a student leader with Youth United for Climate Action, is from the Muscogee Nation of Oklahoma. Johnson grew up in New Mexico and knows first-hand about the state’s underfunded schools.

“I remember in elementary school we would have a list: bring three boxes of tissues, or colored pencils,” she said, speaking of Chaparral Elementary School in Santa Fe. “As students and as teachers, [you’re] buying the supplies for the classroom.”

Johnson remembers being told as a child that the schools she attended ranked second worst in the nation. If New Mexico’s education system is indeed that bad, she said, how can officials continue to think that accepting a funding structure that delivers such a consistently poor result is a good idea?

“At the end of the day the system that we have now that is being paid for by oil and gas doesn’t work, and we know it doesn’t work,” Johnson said. “It’s the whole ‘Don’t bite the hand that feeds you’ kind of mentality,” she said, linking the industry’s patronizing messaging around its support for schools to a direct legacy of colonization.

“I don’t want to have to rely on this outside entity. I don’t want to have to rely on this broken system. I want better for my kids and their kids and my whole community.”

Kids and Climate Change: New Book Exposes Why Some Schools Fail to Teach the Science

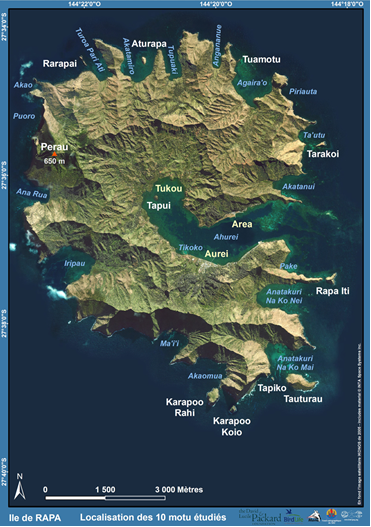

Rapa is the most southeastern island of the Austral Archipelago in French Polynesia. Ten islets, ranging in size from two to 64 acres, surround the main island, with a total land area of just 15.6 square miles (about 40 square kilometers). Rapa is sometimes called Rapa Iti, or “Little Rapa,” to distinguish it from Rapa Nui (better known as Easter Island). As of 2017 Rapa had a population of 507 people, a unique community that still follows old Polynesian traditions and speaks its own Polynesian language, Rapa. There are three main villages — Ahurei, Tukou and Area — all located around the central bay. It’s the only island in the country that has a winter season, usually between May and October, when the temperature can go down to 37 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius). That temperature difference is one reason there are seabirds and plants living here that don’t live in other parts of French Polynesia.

Rapa is the most southeastern island of the Austral Archipelago in French Polynesia. Ten islets, ranging in size from two to 64 acres, surround the main island, with a total land area of just 15.6 square miles (about 40 square kilometers). Rapa is sometimes called Rapa Iti, or “Little Rapa,” to distinguish it from Rapa Nui (better known as Easter Island). As of 2017 Rapa had a population of 507 people, a unique community that still follows old Polynesian traditions and speaks its own Polynesian language, Rapa. There are three main villages — Ahurei, Tukou and Area — all located around the central bay. It’s the only island in the country that has a winter season, usually between May and October, when the temperature can go down to 37 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius). That temperature difference is one reason there are seabirds and plants living here that don’t live in other parts of French Polynesia.

That’s climate chaos for you: a series of unpredictable and dangerous events making life more complicated and deadly.

That’s climate chaos for you: a series of unpredictable and dangerous events making life more complicated and deadly. Our take: If we ever hope to meet the goal of protecting 30-50% of the planet, we’d better start recovering some of the land and water we’ve lost in the first place. Rewilding ain’t easy, but it’s going to be essential.

Our take: If we ever hope to meet the goal of protecting 30-50% of the planet, we’d better start recovering some of the land and water we’ve lost in the first place. Rewilding ain’t easy, but it’s going to be essential. Our take: Gies has written a bevy of articles about “Slow Water” over the past few years, and we’re glad to see her tackle the topic in book form.

Our take: Gies has written a bevy of articles about “Slow Water” over the past few years, and we’re glad to see her tackle the topic in book form. Our take: We’ve followed Linden’s writing for years. Here he offers vital history as a window to the future.

Our take: We’ve followed Linden’s writing for years. Here he offers vital history as a window to the future. Our take: Chomsky’s previous books have focused on immigration, labor exploitation and related issues, and she brings an awareness of racism and equity to her discussion of climate change (which, despite the book’s title, offers a fair amount of science for those readers who are new to the danger it poses).

Our take: Chomsky’s previous books have focused on immigration, labor exploitation and related issues, and she brings an awareness of racism and equity to her discussion of climate change (which, despite the book’s title, offers a fair amount of science for those readers who are new to the danger it poses). Our take: This series of enthusiastic educational graphic novels takes a hybrid approach that combines character-based stories with easily followed how-to lessons. This latest volume joins earlier editions on science experiments, robots and gardening.

Our take: This series of enthusiastic educational graphic novels takes a hybrid approach that combines character-based stories with easily followed how-to lessons. This latest volume joins earlier editions on science experiments, robots and gardening. Our take: Berwald gave us a flavor of this moving book in her essay “

Our take: Berwald gave us a flavor of this moving book in her essay “ Our take: Sex sells, but is using a sexy cover photo the wrong idea for a book about a dangerous pesticide? Check out this

Our take: Sex sells, but is using a sexy cover photo the wrong idea for a book about a dangerous pesticide? Check out this  Our take: A philosopher and former journalist, Cripps addresses the climate crisis through the lenses of morality, ethics and justice. She makes you care about climate change’s most vulnerable victims and in the process offers advice on how we all can help.

Our take: A philosopher and former journalist, Cripps addresses the climate crisis through the lenses of morality, ethics and justice. She makes you care about climate change’s most vulnerable victims and in the process offers advice on how we all can help. Our take: This is the third book in Kaufmann’s unique series of “field atlases,” which combine art and science into a beautifully illustrated guide for any naturalist or nature lover. For a flavor of what to expect, check out Kaufmann’s essay about one of California’s most beautiful but overlooked trees, “

Our take: This is the third book in Kaufmann’s unique series of “field atlases,” which combine art and science into a beautifully illustrated guide for any naturalist or nature lover. For a flavor of what to expect, check out Kaufmann’s essay about one of California’s most beautiful but overlooked trees, “ Conflict of Interest Department: Stark, a former journalist, is a fellow Center for Biological Diversity employee who helped launch The Revelator. His latest book is a riveting examination of the extinction crisis by way of a prehistoric loss.

Conflict of Interest Department: Stark, a former journalist, is a fellow Center for Biological Diversity employee who helped launch The Revelator. His latest book is a riveting examination of the extinction crisis by way of a prehistoric loss.