Adapted from Why Sharks Matter: A Deep Dive With the World’s Most Misunderstood Predator by David Shiffman. Copyright 2022. Published with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

Shark bites are, statistically, so unlikely that in all functional reality you will never experience one. Chapman University conducts an annual Survey of American Fears in which they ask a random sample of Americans about things they’re afraid of. In 2017, sharks were the #41 fear of Americans, with more than 25% of respondents reporting that they are afraid of them. That’s tens of millions of people who are afraid of an animal that kills fewer people than being careless while taking selfies. So why are so many people so afraid of sharks?

As reported in a June 27, 2019, National Geographic article about the psychology of fear, people are afraid of sharks for a fairly simple reason: because sharks are large wild animals that can hurt or kill you. It makes sense to be afraid of potentially dangerous animals, despite the very small risk. The fact that they usually don’t hurt people doesn’t mean that they can’t or won’t hurt you. Humans are hardwired to try and avoid being killed by wild animals, which also explains our fear of things like snakes, which are also extremely unlikely to harm you. In general, humans are really bad at conceptualizing relative risk, something that plagues not only the discourse surrounding sharks but also lots of political issues, including gun control, immigration, and the global war on terrorism.

Since that’s a relatively unsatisfying explanation, I’ll go into a little more detail.

Inflammatory Media Coverage of Sharks

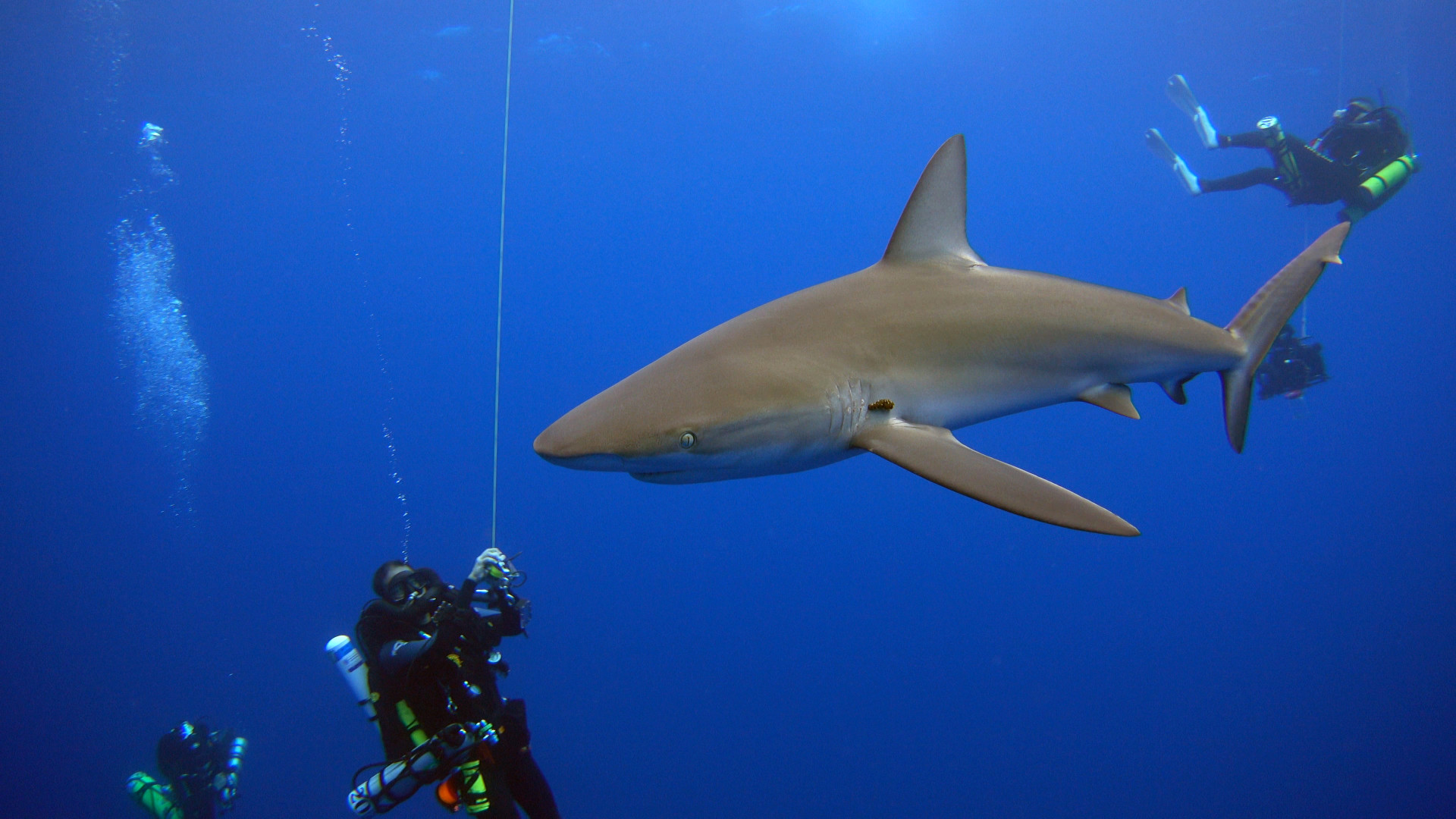

Sharks are a frequent subject of popular press coverage, and are rarely covered in a positive light. A 2012 Conservation Biology article looked at hundreds of examples of sharks being written about in major U.S. or Australian newspapers. The authors found that the most common topic of these articles, by far, was sharks biting humans. More than half of all articles about sharks in major papers from 2000 to 2010 were about a shark bite; only 11% even mentioned shark conservation. The article pointed out that this focus on shark violence is likely to be a problem and suggested that experts make an active effort to speak with the popular press about shark research and conservation topics instead of shark bites.

Eagle-eyed readers may have noticed that I’ve been using the phrase “shark bites” and not the term “shark attack,” which you may be more familiar with. When you hear the phrase “shark attack,” you picture the shark from Jaws, a malicious creature stalking the coast and killing intentionally simply because it’s evil. As we’ve seen, that’s just not what happens; the phrase “shark attack” is therefore misleading and inflammatory. A 2013 paper by Robert Hueter and Christopher Neff instead suggested a new typology of shark–human interaction terms, including “shark sighting,” “shark encounter,” “shark bite,” and “fatal shark bite”; I use their terminology here.

Due to the “if it bleeds, it leads” principle of some unscrupulous strains of journalism, whenever any shark bites anyone anywhere in the world, it’s headline news everywhere. This creates the false impression that these events are much more common than they really are, especially when very minor bites get inflammatory coverage. The same 2013 Neff and Hueter paper I mentioned above performed a content analysis of how shark “attacks” were covered in the Australian press, and found a startling statistic: in 38% of reported “shark attacks,” THE SHARK DID NOT EVEN TOUCH THE HUMAN. It simply swam near them in a way that the person found threatening or scary.

Sometimes inflammatory media coverage is pretty easy to identify: “Shark Research Makes Us No Safer,” “Blood in the Water But Experts Are Still at Sea,” “Conservation Policies Value Sharks Over Human Lives,” “Has Our Admiration For Sharks Gone Too Far?”, “Great White Shark: Endangered or Just a Danger to Humans?” These are all headlines from one columnist at one newspaper (Fred Pawle at the Australian) that date to the last couple of years. But even the regular language used by journalists who aren’t conspiracy theorists can be inflammatory and fear-mongering. Referring to the ocean, which is a shark’s home, as “shark-infested waters” suggests that there’s something wrong or bad about sharks being there. Referring to wild animals accidentally injuring people as “bloodthirsty” or “monsters” is incorrect and perpetuates public fear and misunderstanding. Similarly, a shark swimming normally and minding its own business is neither “lurking” nor “stalking” humans.

Sometimes popular press coverage is inflammatory even when it’s not talking about sharks that bite people. One particularly egregious example of this happened in January 2015, when some Australian fishers caught a frilled shark in their nets. This long and skinny deep-sea dweller has small but sharp teeth and a snake- or eel-like body. It can grow up to six feet long. Headlines about this incident included words like “Horrific” (NPR), “Terrifying” (the Independent), and “Like a Horror Movie” (Fox News). CNN asked, “What brought this deep-sea monster to the surface?” (It was probably the giant net that it got caught in.)

Sometimes this media coverage takes the form of misidentifying a species in a way that inspires public fear. Recall that, in addition to shark bites being vanishingly rare, most shark species have never killed a human. One outrageous example of inflammatory coverage appeared in a 2014 Daily Mail article, which asked “Is this a great white off the coast of Cornwall?”

Even a cursory glance at the image presented showed that it was clearly not a great white — a sometimes-dangerous and fear-inspiring species — but rather a harmless, plankton-eating basking shark. In an article I wrote for New Scientist analyzing this particular case, I pointed out a series of major flaws in this Daily Mail article. For one thing, the author, Harriet Arkell, didn’t interview a single qualified credentialed expert. She did, however, interview a fisher who wrongly claimed that the only large fish in UK waters were great whites.

Making a common but nonetheless grievous error, Arkell also interviewed a self-described “shark aficionado” (read: someone who thinks sharks are neat but doesn’t have any relevant credentials or expertise). As I wrote at the time, “Why quote a shark aficionado, a non-expert who thinks sharks are cool, for a story like this? Can you imagine if journalists did this for other types of story? The White House announced intentions to bomb Islamic State targets in Syria, but counterterrorism aficionado Steve said that he’s pretty sure the organization is actually hiding in Peru. Markets cheered the move to reduce interest rates, but finance aficionado John said that everyone should just buy gold and bury it in their backyards. It would never happen, because it’s ridiculous.”

Similarly, a much-hyped 2013 photo allegedly showed a SHARK IN THE WATER NEAR CHILDREN! Looking at this photo, though, it clearly reveals that the animal in question is not a shark, but a dolphin — which means that an entire week of fear-inducing news was about literally nothing at all. It’s perhaps worth noting here that several of the self-described shark experts who claimed this was a shark were non-scientists who regularly appear on Shark Week programming.

Sometimes, this fear-inducing media coverage could just as easily be dubbed “Fish Seen in Water,” as in the case of a November 2017 Facebook post by CBS Miami with the headline “Spine-Tingling Swim: Tiger Shark Swims Extremely Close to Miami Beach.”

The shark in question didn’t bother anyone, it was just swimming in its natural habitat. Similarly, a February 2018 article in the Charlotte Observer had the headline “A Dangerous Mako Shark Is Haunting NC’s Outer Banks and Won’t Leave.” This shark didn’t so much as smile at anyone. It was swimming through its home, but that particular newspaper headline is calculated to frighten. And it “won’t leave?” Where do you want it to go? It lives in the ocean! Sometimes these articles mention that a shark is “near a beach,” which is another way of saying “in the water, which is its home.” And while we’re talking about this, I’d like to inform Shark Week shows like Shallow Water Invasion that this behavior isn’t new. Sharks always feed near shore; what’s new is everyone has a camera with them all the time, whether it is an iPhone or a drone or a GoPro.

In recent years, particularly flagrant examples of inflammatory media coverage have featured drone footage that shows a shark swimming near humans without bothering them at all. The big story is apparently that the people had a lovely day at the beach without even knowing a shark was near them — isn’t that TERRIFYING?

This kind of sensationalist and inaccurate media coverage is a frequent source of frustration for shark scientists, educators, and conservationists.

Copyright 2022 David Shiffman

Previously in The Revelator

Langkawi is a place of geological significance, a cluster of 109 tropical islands sitting at the interface between the Straits of Malacca and the Andaman Sea. The archipelago’s natural history dates back more than 550 million years, making it the oldest part of Malaysia and the first landmass in Southeast Asia to have emerged from the seabed. The archipelago is celebrated for its ancient rock formations and geological structures, with plenty of minerals and fossils.

Langkawi is a place of geological significance, a cluster of 109 tropical islands sitting at the interface between the Straits of Malacca and the Andaman Sea. The archipelago’s natural history dates back more than 550 million years, making it the oldest part of Malaysia and the first landmass in Southeast Asia to have emerged from the seabed. The archipelago is celebrated for its ancient rock formations and geological structures, with plenty of minerals and fossils.

This story is part of “

This story is part of “