This year the United States could experience its first bird extinction in more than three decades.

That’s the warning from the scientists and conservationists working to protect the critically endangered Florida grasshopper sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum floridanus). Once common in the grasslands of central Florida, this geographically isolated subspecies has experienced a catastrophic population decline since the 1970s, mostly due to habitat loss and degradation. Although the tiny birds have been protected by the Endangered Species Act since 1986, their numbers have continued to fall — to the point where recovery now seems next to impossible. A survey last year found that just 22 females and 53 males remained in the wild — and that was before 2017’s hurricane season and record-setting winter cold snaps.

“Extinctions really happen,” warns Paul Reillo, zoologist and president of the Rare Species Conservatory Foundation in Loxahatchee, Fla. “This is going to be North America’s next extinct bird if we do nothing.”

Reillo says there’s just one option left to save the Florida grasshopper sparrow: the captive-breeding program that began in 2015. “Captive breeding is never anyone’s desire, and it’s always the approach of last resort,” he says. “Given the collapse of the wild population it’s not only the last option, but it’s the last of the last options.”

Getting to this point took several years of debate among the various government agencies and partner organizations working to protect the birds. Finally the first sparrow eggs and juvenile birds were brought into captivity at the Rare Species Conservatory and the White Oak Conservation Center plantation near Jacksonville in 2015 and 2016, respectively.

Learning to Live

As with any captive-breeding program, learning how to get the birds to mate and hatch outside their native habitat has been a complex process. Early attempts to hatch the birds’ tiny eggs failed before the team established the proper temperature, humidity and incubator-rotation procedures. They learned quickly, though; by May 2016 a successful artificial incubation protocol had been established. The first captive-laid eggs hatched that month at the conservatory. Several additional chicks have been born since that point, although not all have survived. The captive population now stands at a total of 48 birds, with 29 living at the conservatory in Loxahatchee.

Beyond figuring out how to hatch the birds, the conservation teams also learned more about the adult birds, specifically the critical role of parenting. For one thing, the birds they’ve hand-reared never learned how to act like wild birds and “tend to be very poor parents,” Reillo says. Breeding pairs rarely work together to build nests, while females sometimes lay eggs outside of their nests and then fail to sit on the eggs until they hatch. Most of the females who did successfully nest often fed their chicks improperly, while males were rarely attentive to any part of the reproductive process except for mating — a big change for a species that engages in bi-parenting in the wild. During 2016 and 2017 most of the fertile eggs laid at the facilities had to be artificially incubated and then hand-reared after hatching, a process that could conceivably extend this cycle of parental neglect.

Parenting is also important in other ways. Although chicks can be raised by humans to become healthy adults, they need some quality time with their parents first. “The first two to three days of parental care stimulate all sorts of wonderful things, the most important of which seems to be the bacteria in the gut flora that enables a healthy immune system to develop,” Reillo says. “We cannot replicate that.” The facilities have managed to raise more than a dozen chicks whose eggs were removed from their parents after just a day, but “it’s extremely difficult and it often ends in disappointment because they develop septicemia and often there are infections that the chicks can’t overcome,” he says.

A Threat Revealed

Another immunological challenge has revealed itself through the captive-breeding program: Many of the birds, they found, have become afflicted with a previously unknown protozoan parasite that starts in the intestines and then invades vascular tissue in the liver, heart, spleen and other organs. This causes high mortality in the sparrows, particularly young birds, as well as birds stressed by factors such as cold, handling or even breeding.

Reillo says we might not have learned about this parasite without the captive-breeding program. “When birds die on the landscape the bodies disappear very quickly, and you can’t explain the mortalities,” he says. That’s why there has never been what he calls a “unifying explanation” for the collapse of the wild population. Captivity, on the other hand, provides a more controlled setting and gives the scientists “a window into some of these problems facing the birds that otherwise you would not see in the wild.”

Although the parasite’s still killing some captive birds, the conservation teams have learned how to detect and treat it. “We’ve stumbled across a means of controlling it and we do have a therapy that clears this organism from birds very quickly,” Reillo reports. “But so far we’ve only found one such drug that actually works well. That’s a concern because whenever you use one thing over and over again there’s a good chance that the target organism will evolve some resistance to it, and then you’ve got a real serious problem because you’ve got something that you can’t treat.”

What Happens Now?

The next step involves finding out more about how parasites and other potentially transmittable threats affect the birds both in captivity and in the wild. Larry Williams is the Florida supervisor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the lead agency in the birds’ conservation efforts. He says disease analysis is being conducted and is expected to be completed by March. In April the wild population will be surveyed “so we’ll have a feel for how many birds survived the winter.” Once that’s complete the species’ conservation working group will meet in mid-May to make a final plan for possibly collecting any of the remaining wild birds and bringing them into captivity.

“We’re being really careful about this,” Williams says. “If the working group says our plan will be to bring in 10 females, then we want to have the cages and capacity in the captive facilities to handle those 10 new females. We don’t want to be sitting there at May 15 saying ‘bring in 10’ when nobody thought to build the cages to house them.” He expects that if the working group gives the go-ahead to start collecting more wild birds, the effort would start in June when the birds are nesting, so both mothers and eggs can be brought into the breeding facilities.

One big hurdle looms over all of this: money. After investing millions of dollars on field research, mitigation efforts and launching the captive-breeding program, the Fish and Wildlife Service has requested an additional $150,000 to $200,000 for future captive-breeding efforts. But federal funding for many endangered species programs is up in the air under the Trump administration. Reillo says “we’re not counting on the federal government actually providing tangible resources for this program going forward.” The Fish and Wildlife Foundation of Florida is currently raising funds to help the captive-breeding program, as is the Rare Species Conservatory through Florida International University’s Tropical Conservation Institute, the latter with a matching-grant program.

Another obstacle for this entire effort: Some of the captive birds may not live much longer. Florida grasshopper sparrows typically only live four to five years in the wild, and Reillo reports that several of the birds in their collection are already older than that. “Why they’re still alive is anybody’s guess,” he says. “They’re on borrowed time.”

Hope Springs Eternal

If most or all of these many difficult problems can be overcome, there is actually hope for this subspecies. Although the sparrows are relatively short-lived, they make up for it with several biological advantages. “These birds are hardwired for rapid reproduction,” Reillo says. Parents incubate eggs for just 11 days, and chicks can start leaving the nest at nine days before becoming completely independent just after three weeks of age. They start reproducing about one year later, and females can lay three to four eggs at a time, with as many as five clutches in a season. “So a female may be able to produce up to 20 chicks a year,” Reillo says. “It is a species that is engineered and has evolved for rapid population growth.” That means the captive population could conceivably grow fast enough and large enough that a release program could be considered some time down the road.

Of course, getting to that point won’t be possible without additional potential breeders, and every day that passes without bringing more wild birds into the captive population is a day when the total population could shrink even further. “Every single life is precious for these birds,” Reillo says.

Ultimately what happens next depends on the people who have devoted their lives to saving the Florida grasshopper sparrow from extinction. “I’m worried about our ability to save the species,” Williams admits, “but I’m confident that the people working on it are doing the absolute best work possible.”

Previously in The Revelator:

When people think of climate change, they think of the damages, physical and economic, deriving from it. However, there is also the other side of the problem. Mitigating climate change is forcing us to rethink the way we move around, produce goods, generate electricity, feed ourselves, and many other aspects of human activities.

When people think of climate change, they think of the damages, physical and economic, deriving from it. However, there is also the other side of the problem. Mitigating climate change is forcing us to rethink the way we move around, produce goods, generate electricity, feed ourselves, and many other aspects of human activities.

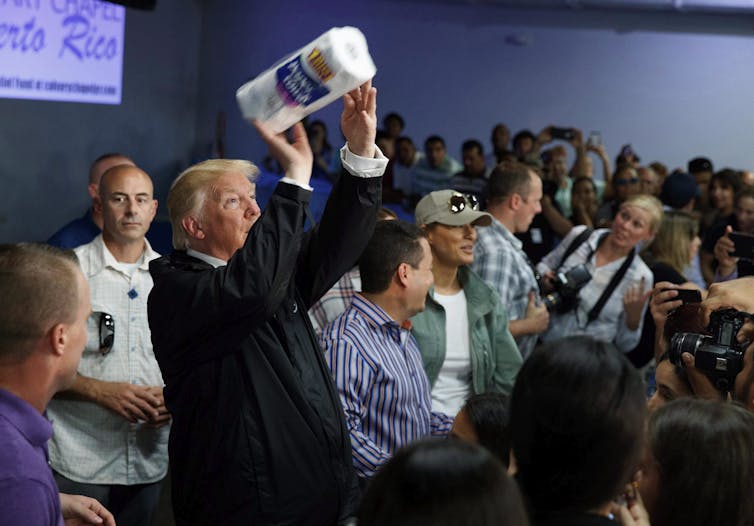

It’s hard to believe that we are still at a point where people need to be persuaded that climate change is a problem for people, here and now, including you and me and all our friends and relations. With the devastation caused by the insane 2017 Atlantic hurricane season, the wildfires running rampant throughout the American West, daily flooding from sea-level rise in major American cities, heat waves year after year, ongoing changes in local fauna and flora, and the extraordinary expenses being taken on by cities and states to adapt to these impacts, one would hope the point has become clear.

It’s hard to believe that we are still at a point where people need to be persuaded that climate change is a problem for people, here and now, including you and me and all our friends and relations. With the devastation caused by the insane 2017 Atlantic hurricane season, the wildfires running rampant throughout the American West, daily flooding from sea-level rise in major American cities, heat waves year after year, ongoing changes in local fauna and flora, and the extraordinary expenses being taken on by cities and states to adapt to these impacts, one would hope the point has become clear.

One could argue that climate change is all about people, and that a need to “put a human face” on it would be totally unnecessary. However, we know that is not what happens. Concerns range from lifestyles to the economy, when they should be about livelihoods and the society as a whole, not only the economic aspect.

One could argue that climate change is all about people, and that a need to “put a human face” on it would be totally unnecessary. However, we know that is not what happens. Concerns range from lifestyles to the economy, when they should be about livelihoods and the society as a whole, not only the economic aspect.

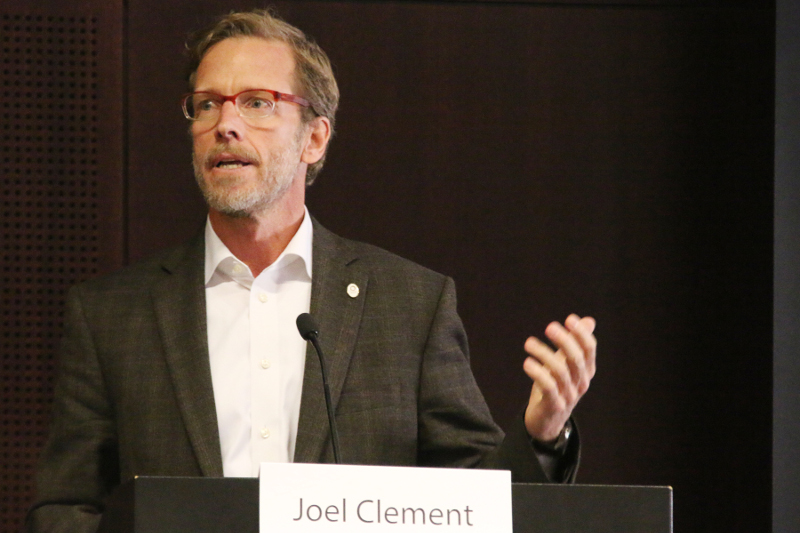

This is going to sound obvious, but I think it’s simply about telling the stories of people, here and elsewhere, already significantly and demonstrably affected by ongoing climate change, illustrating the hardship they are facing while warning that it’s still only a preview of things to come. It’s about finding the human canaries in the climate change coal mines.

This is going to sound obvious, but I think it’s simply about telling the stories of people, here and elsewhere, already significantly and demonstrably affected by ongoing climate change, illustrating the hardship they are facing while warning that it’s still only a preview of things to come. It’s about finding the human canaries in the climate change coal mines.