Last week angry headlines around the world decried the news that the Trump administration had issued trophy-import permits for 38 lions killed by 33 hunters — including many high-rolling Republican donors — between 2016 and 2018.

Lions (Panthera leo leo) have experienced massive population drops over the past two decades. The big cats gained some protection under the Endangered Species Act in 2016, but the Obama-era regulations still allowed some hunting and trophy imports as long as the host countries could prove that their hunts were sustainable. The Trump administration did away with that requirement last year and instead decreed that it would allow imports on a “case-by-case basis.”

Those 38 dead lions represent the Trump administration’s shift on hunting of endangered species.

More worrying than these trophies, however, was a story that came out around the same time but barely made a blip on the media’s radar. Just a few days before news of the Trump-era lion imports became public, a leaked letter from the South Africa Department of Environmental Affairs revealed that it had nearly doubled the amount of lion bones and skeletons it would allow to be exported from the country, from 800 a year to 1,500.

That’s a dramatic increase from the 573 lion skeletons exported from South Africa in 2011, which itself was nearly double the number of exports shipped during the three-year period of 2008 to 2010.

Unlike the lions slain by hunters, the South African bones will come from the country’s 200-plus lion farms, where the big cats are raised — often in terrible conditions — for use in “caged hunts.” There, according to the 2015 documentary Blood Lions, foreign hunters pay as much as $50,000 for the opportunity to shoot semi-tame lions in small, walled-off, inescapable encampments. The heads and skins from these caged hunts become trophies, but the rest of the bodies — and many of the other lion carcasses from the factory farms — are shipped to Asia, where the bones are ground down to be used as “medicine” and as a component in wine. (There is no medicinal quality in lion bones.)

These factory farms are believed to contain about 8,000 captive-bred lions — an astonishing number compared to the fewer than 20,000 lions estimated to still live in the wild throughout Africa. South Africa itself is estimated to hold fewer than 2,000 adult wild lions.

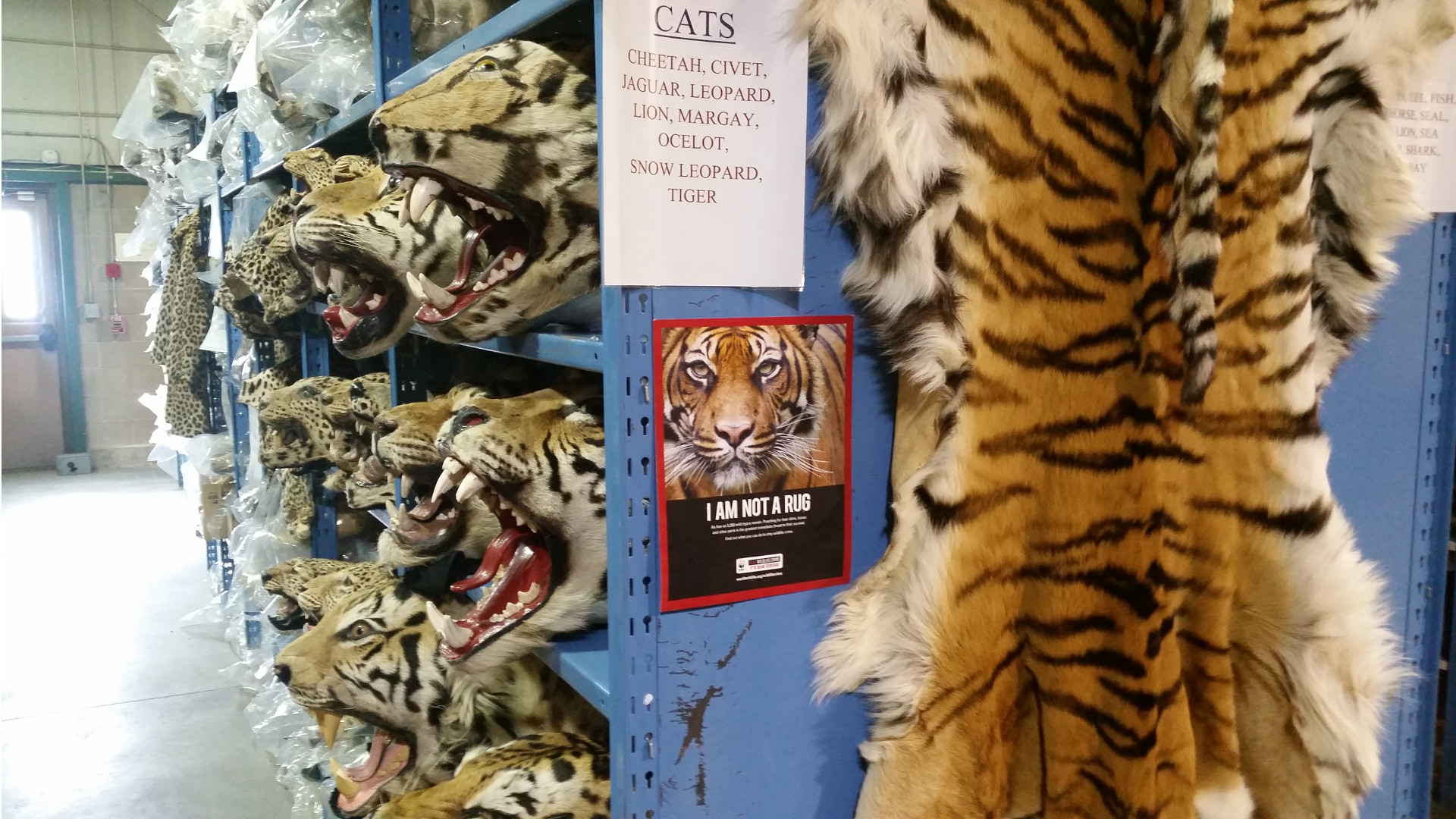

Where does this demand for lion products come from? Many experts say the increase in the lion-bone trade is a response to the decline in wild tiger populations in Asia. Tigers are also poached for “medicinal” products, although those big cats have become so rare in the wild — an estimated 3,900 animals spread across a dozen countries — that the industry has been forced to turn to other felines to feed its fortunes.

“The lion never had any traditional value in China, but it’s an analog to the tiger so it seems to be acceptable,” Luke Hunter, chief conservation officer of the big-cat conservation organization Panthera, told me in 2016.

As more lions enter the legal bone trade, the danger to wild lions increases. A July 2017 report from the Environmental Investigation Agency said that legal trade in lion bones further threatens wild tigers and lions by stimulating demand for products made from their bodies. In traditional Asian medicine, wild products are considered more potent and valuable than farm-raised equivalents.

Interestingly enough, the farms and lion-bone trade appear to also be inspiring an increase in the poaching of captive lions. A report issued last month found that at least 60 captive lions in South Africa have been killed by poachers since 2016, with dozens of additional attempted killings.

At least five captive tigers were also killed in South Africa during the same time period. It is unclear how many tigers exist in South Africa, but the country has exported more than 200 captive-bred tigers over the past five years, according to a recent report. About half of those cats were exported to Vietnam and Thailand, hubs of tiger-product smuggling activity.

All of this is big business and while most of it is legal, some of it may not be. Another new report, issued last month by two South African organizations called the EMS Foundation and Ban Animal Trading, accused the legal lion-bone trade of shipping a much greater quantity of bones than officially reported. The two organizations used their report to call for eliminating all lion exports from South Africa, restricting the breeding of lions and other big cats, and investigating the finances of breeders.

What does the future hold for wild lions? A 2015 study predicted that wild lions would see another 50 percent population decline over the next two decades due to poaching, the bushmeat trade (which often catches lions in snares intended for other wildlife), retaliatory killings for predation of livestock, and habitat loss. Add legal trophy hunting and poaching inspired by the legal bone trade into the mix and that timeline may become accelerated — and lions throughout Africa could pay the price.

It’s the height of summer, and there’s no better way to while away the hot August evenings than to curl up with a good book. Luckily there are dozens of great new environmental books coming out in August to keep you reading all month long. Here are 13 thought-provoking new titles publishers have scheduled for release this month, with books for dedicated conservationists, animal-loving kids, history buffs and everyone in between.

It’s the height of summer, and there’s no better way to while away the hot August evenings than to curl up with a good book. Luckily there are dozens of great new environmental books coming out in August to keep you reading all month long. Here are 13 thought-provoking new titles publishers have scheduled for release this month, with books for dedicated conservationists, animal-loving kids, history buffs and everyone in between.

It is fantastic to see that World Pangolin Day has grown into a global event which is now recognized by pangolin people all over the world — local on-the-ground conservation programs, schools, artists, big international NGOs , as well as high-profile institutions such as the United Nations (CITES), USAID and the IUCN.

It is fantastic to see that World Pangolin Day has grown into a global event which is now recognized by pangolin people all over the world — local on-the-ground conservation programs, schools, artists, big international NGOs , as well as high-profile institutions such as the United Nations (CITES), USAID and the IUCN. I have been following the global wildlife trafficking crisis for about 10 years now. I can’t say I was at all surprised when illegal trade in jaguar teeth and bones surfaced and was linked to the famously insatiable Chinese demand for big cat body parts.

I have been following the global wildlife trafficking crisis for about 10 years now. I can’t say I was at all surprised when illegal trade in jaguar teeth and bones surfaced and was linked to the famously insatiable Chinese demand for big cat body parts.

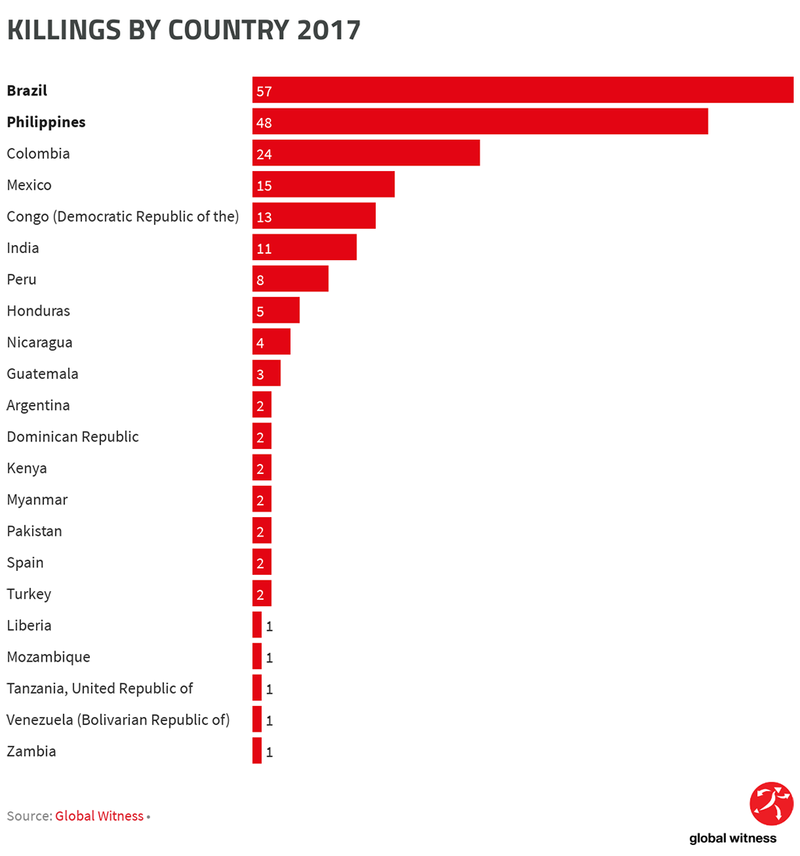

Intimidation

Intimidation