The United Nations this week released a powerful report on the state of nature around the planet. Among its disheartening conclusions, the report — by hundreds of experts from 50 countries — estimates that a staggering 1 million species are at risk of extinction in the next few decades due to human-related causes.

Let’s unpack that a bit.

The report bases its estimate on the number of known species on the planet — about 8 million — and what we know about how many of those species are already at risk of extinction.

For example, more than 40 percent of the planet’s amphibian species are threatened with extinction, along with about a third of the shark family and a third of marine mammals. The report also estimates that about 10 percent of insect species are at risk, a fact highlighted by all of the recent news about the impending “insect apocalypse.”

That’s all bad enough, of course, but there’s something the UN report doesn’t discuss: In all likelihood the number of species on the planet is actually much higher than 8 million, meaning that even more species are probably at risk.

How many species are we talking about? One 2017 study pegged the worldwide level of biodiversity at an amazing 2 billion species. Another study in 2016 used mathematical models to come up with an even higher number, between 100 billion and a trillion.

A lot of those extra billions of species are “just” microbes, so they’re not exactly your easy-to-count and easier-to-mourn megafauna like rhinos, wolves and orangutans. But they’re still an important part of the ecosystem. As the more visible species go extinct, it’s likely they will too.

It’s all connected, you see. A soil microbe disappears and maybe that loss contributes to a tree also dying off. That tree produced fruit, so the birds and monkeys that visited its seasonal buffet then suffer. After that the predators that eat the birds and monkeys disappear. Meanwhile we’ve lost the insects that pollinated the tree, the snails that helped break down its decaying leaves and branches, the snakes and lizards that ate the snails and insects, and probably more microbes along the way.

It’s an organic game of Jenga. Remove enough parts of the system and the entire thing threatens to collapse.

We see this on islands and other restricted ecosystems all the time. Species evolve into incredibly specific microhabitats, which themselves become incredibly susceptible to disruption. Change the temperature a degree or two, alter the rainfall a tiny bit, remove a key pollinator, or plow the whole thing over with a bulldozer and species go extinct in the blink of an eye — often before they’ve ever been observed, described or named by scientists, or before conservationists can issue a call to protect them.

Of course, the numbers we’re talking about here are almost impossible to comprehend, whether we’re talking about 1 million or hundreds of millions. That makes it hard to motivate action or to establish policy — after all, how do you broadly say “let’s protect a million unnamed species” when we can barely get our society motivated enough to save iconic species like the northern white rhino?

What makes it worse is that virtually none of these extinctions will take place out in the open. There will be few if any endlings — the last individuals of their kind — in public view, slowly dying off one by one in a zoo or on a well-watched mountain top. Most species will drift away in caves, in the ocean, in the ground, or in the air, one by one, bit by bit, dying by a thousand papercuts, until they’re wiped out in one fell swoop or until there are too few remaining individuals to find each other and reproduce. Then they’ll go extinct far away from human eyes, and it may take decades of searching to scientifically prove that they no longer exist.

That’s just for the species we know enough about to look for in the first place.

And if we don’t explicitly see an extinction happen, does it matter to most people?

Toward this issue of getting people to notice and care, the UN report takes an interesting path. It positions the extinction crisis and the general decline of nature as something that will affect the very thing causing it — humanity. The loss of species, the report points out, will threaten global food security and water supplies and even make the climate crisis worse.

Will that “ecosystem services” approach get people, especially policy makers, motivated? We’ll see. The extinction crisis is also, in my mind, a crisis of morality: a resource in short supply these days, at least in the leadership of a particular country that comes to mind.

Still, the report also includes a long list of policy recommendations for leaders around the world. These include important goals for sustainable energy, sustainable food growth, forest conservation, freshwater protection and Indigenous land management.

Will leaders hear the call? I’m actually a bit heartened. This report was front-page news on The New York Times and hundreds of other media outlets. The news was shared widely on social media. People got angry. And scared.

And the story isn’t going away any time soon. The UN’s report is just an early summary for policy makers; the full version will come later this year, providing numerous opportunities to keep talking about it.

But the time for simply talking is long past over. As this report makes perfectly clear, it’s now or never for us to take conclusive action — on an individual basis, at a country level, and as a human society.

Whether that happens — or whether it happens fast enough — remains to be seen. Meanwhile, we’re undoubtedly already losing many of those 1 million species, and we’re about to lose more. The numbers will soon start to stack up, and along the way they’ll also speed up, with ecosystems collapsing and extinctions happening faster and faster.

That’s a bleak outlook, but many believe we can still turn things around. Sir Robert Watson, the chair of the UN body that issued the report, said in a press release that “it’s not too late to make a difference.”

He added that it won’t be easy, though, indicating that it will require a transformative shift in how human society operates.

“By transformative change, we mean a fundamental, system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values,” Watson said. This, he added, will face “opposition from those with interests vested in the status quo,” but he continued by saying that “such opposition can be overcome for the broader public good.”

And maybe for the good of a few thousand species along the way.

![]()

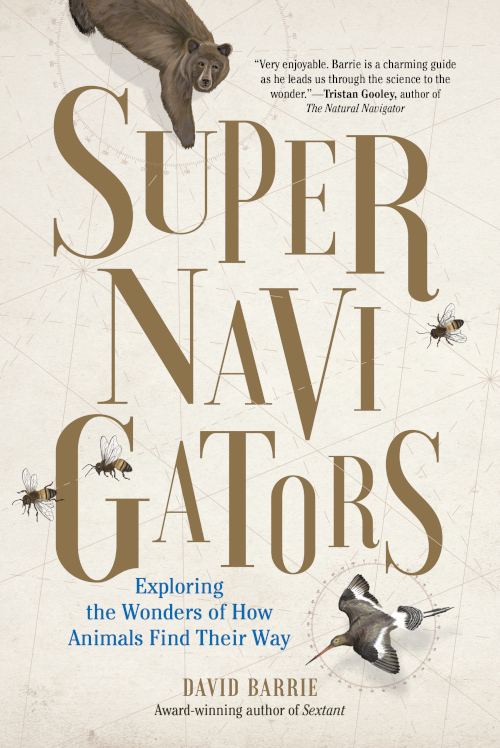

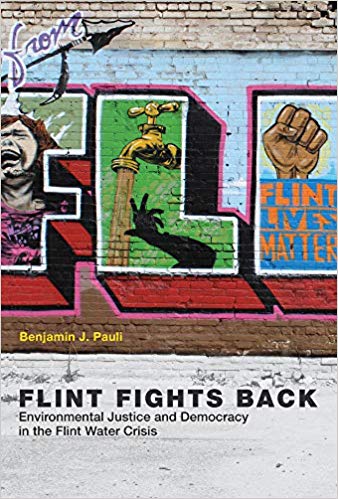

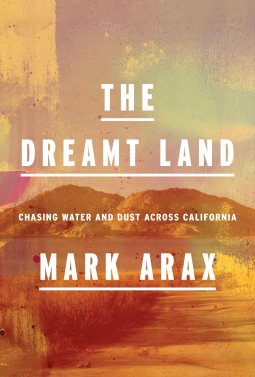

Looking for something new to read? We’ve got you covered. Here are our picks for the best environmentally themed books of May 2019 — and it’s quite a collection, with 13 new titles about a pioneering conservationist, the history of water woes in California, the dirty legacy (and future) of coal, and even the psychology of climate change.

Looking for something new to read? We’ve got you covered. Here are our picks for the best environmentally themed books of May 2019 — and it’s quite a collection, with 13 new titles about a pioneering conservationist, the history of water woes in California, the dirty legacy (and future) of coal, and even the psychology of climate change.

The researchers didn’t find much that day because most of the animals they were looking for are more active at night, so they finished their work in mid-afternoon prepared to leave — but not before hearing a series of massive explosions behind them.

The researchers didn’t find much that day because most of the animals they were looking for are more active at night, so they finished their work in mid-afternoon prepared to leave — but not before hearing a series of massive explosions behind them.