Most years the annual gray whale migration along North America’s West Coast is a sure sign of spring. But this year something has gone wrong. Since January at least 167 dead whales have washed ashore from Mexico to Alaska. Scientists expect more in the weeks ahead.

One of the dead whales came to rest at the mouth of a river near my home. This was in May, in south-central Alaska. On a sunny evening my wife and I and our four-year-old daughter went out to see it.

A dead whale has a powerful stink to it, so we approached from the massive animal’s upwind side. It lay on its side in the sun, eyes closed and flukes resting flat on the silty beach. With ravens squawking from nearby cottonwoods and a bald eagle looking on from a riverside snag, we showed our daughter its blowhole, flippers, and the feathery baleen visible along the edges of its open mouth.

With the whale visible from a busy nearby road, a mix of residents and tourists came and went during our hour-long visit. Most stayed just long enough to snap a few photos. But others lingered to peer at the animal’s features or the square incisions biologists had made during their necropsy.

Scenes like this have unfolded up and down the West Coast in recent months. From Baja, Mexico, to Puget Sound to the remote shores of British Columbia, curious humans have strolled out to the continent’s edge to marvel at dead whales. Many brought their children. Some left behind flowers. And nearly everyone asked the same question my young daughter asked: “Why did the whale die?”

Why, indeed? We weren’t the only ones asking. Just a week earlier, the sudden spike led federal scientists to declare an “unusual mortality event,” triggering a special investigation.

Teasing out a common cause amidst all of these widely dispersed deaths can be daunting. Gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) have one of the longest migrations of any mammal, spanning 5,000 miles between Mexico’s Baja Peninsula and northern Alaska. This year’s dead whales have been found along nearly the whole length of their migratory route. At least 37 washed ashore in California, including twelve in San Francisco Bay. Thirty have been found in Washington. During the week of June 17 three whales discovered in Alaska brought that state’s total to ten.

Scientists say the whales on shore represent only a small portion of those that have died.

“It’s a rough calculation, but only about 10 percent of the mortalities are documented,” says John Calambokidis, a research biologist with the Cascadia Research Collective in Olympia, Washington. The remaining 90 percent, he says, either “sink, float out to sea, or otherwise go undocumented.” That means the death toll so far this year could actually be more than 1,000 individuals.

And we’re probably not done yet. Scientists expect more whales will wash ashore in the coming weeks as they continue north toward the Arctic, where they normally spend summers feasting in the rich waters of the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas.

Seeking Answers

Dave Weller, a research wildlife biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in La Jolla, California, says the investigation begins with examining as many of the dead whales as possible before they begin decomposing.

“If we can access a dead whale in time, we can look for evidence of disease, viruses, malnutrition, or human causes such as collisions with ships,” he says.

Scientists along the West Coast have been busy performing necropsies on the dead whales, as described in a recent video from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. They measure the body, identify the sex, and take samples of the organs, blubber and feces. Each sample is a puzzle piece, helping assemble a picture of what’s occurring along the migration route.

Weller says many of the whales show signs of malnourishment. Examinations of a female gray whale found north of Seattle in early May revealed that she had starved to death. Another dead whale in Washington had eel grass in its stomach, evidence of “desperation eating,” according to one observer.

So far no results have been released for the gray whale I visited near my home in Alaska.

It’s not just the dead. Observers have also reported many “extremely malnourished” gray whales swimming off the West Coast this year, according to Calambokidis. Some have detoured into inland waters such as Los Angeles Harbor or San Francisco Bay, where several have been struck and killed by vessels.

Malnourishment makes scientists look north for answers. Gray whales do almost all of their feeding in Alaska, primarily by scooping tiny shrimp-like crustaceans called amphipods from muddy sediments on the ocean floor. They then rely on the fat reserves gained in Alaskan waters to survive their southward migration and the winter mating and breeding season in Mexico.

In one theory, malnourished whales may indicate the animals have reached the natural population level for their Arctic food supply. Population surveys show a steady increase in recent decades, with estimates now at 27,000 animals. It’s a successful recovery from the early 20th century, when commercial whaling reduced numbers to less than 2,000. Some researchers speculate that this year’s mortalities simply reflect the population has outpaced its Arctic food supply, leaving some whales without the reserves needed to return to Alaska.

Another theory is that dramatic warming in the Arctic in recent years has affected the gray whales’ food source. Since 2014 sustained heating in the Bering Sea has triggered an unprecedented loss of sea ice, which may have decreased the productivity of amphipods.

It’s also possible the two theories could be working in concert with each other. When a population reaches its carrying capacity, Calambokidis explains, it can become more vulnerable to environmental fluctuations such as the sudden loss of Bering Sea ice.

If rapidly changing Arctic conditions do play a role, this year’s gray whale deaths will join a growing list of wildlife mortality events connected to warming in the north. They include a massive collapse of West Coast sea star populations, a dramatic decrease in Alaskan cod harvests, and the starvation of thousands of puffins and murres in Alaska, all related to an extreme marine heat wave that began in 2013 in the northern Gulf of Alaska and lasted more than two years. Federal scientists also suspect warming contributed to unusually high mortality among fin and humpback whales in northern waters between 2015 and 2016.

Adding to questions about food web conditions in the Arctic, scores of dead ice seals have washed ashore in recent weeks in northern and western Alaska. Federal scientists have not identified a cause, but a NOAA spokesperson said reports indicate possible malnourishment or abnormal molting among some of the seals.

It’s worth noting that this year’s gray whale deaths are unusual but not unprecedented. In 2000, 131 dead gray whales washed ashore on the U.S. coast during spring migration. Scientists did not conclusively determine the cause, but at least some of the whales were malnourished. Warming from a strong El Niño weather pattern was identified as a possible factor.

While scientists seek answers to the current mass mortality, the gray whale I visited with my family a few weeks ago remains stranded at the mouth of the river. Like the ones found on shores in other states, scientists may let it decompose naturally, a process that could take all summer for this 41-foot-long male.

Before his death this whale likely spent his final months swimming north toward the promise of his Bering Sea feeding grounds. What conditions he would have found there, and how they may affect other arriving whales, for now remains a mystery.

![]()

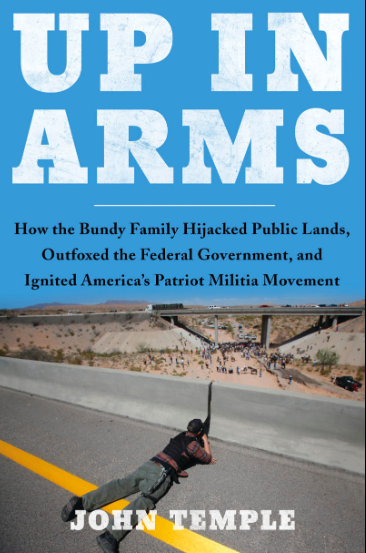

Temple

Temple