HAPPY CAMP, Calif.— Laurel Genzoli is trying to psych herself up to change into shorts, grab her kayak and head to the banks of the Klamath River. But it’s cold — somewhere in the 40s. Summer has swung quickly to fall, and the sun is fighting a losing battle with the thick morning mist that has blotted out the triangle tops of the pine trees.

But cold or not, it must be done.

It’s late September, and Genzoli, an aquatic ecologist, is wrapping up a last day of “summer” research on the Klamath River in Northern California. The day’s task, which begins at a campground in the small town of Happy Camp, is collecting dissolved oxygen sensors that she’s covertly left at seven different locations along more than 100 miles of river, which have been gathering data all season.

The information she’s collecting is part of her research for a Ph.D. at the University of Montana, but it’s also part of a much bigger scientific effort involving multiple state and federal agencies, tribal scientists and other university researchers.

They’re on a tight deadline.

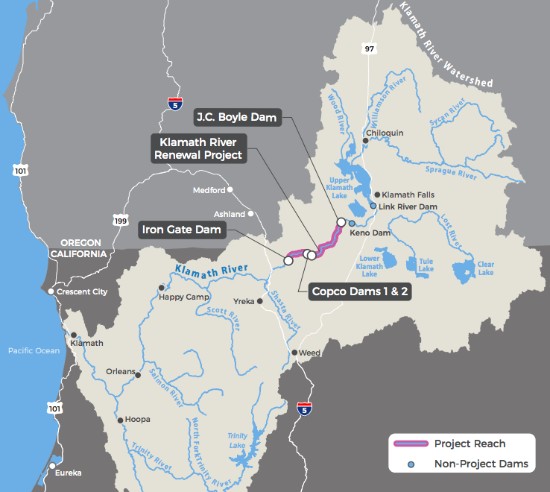

The Klamath is a river in peril, plagued by dangerously poor water quality and collapsing salmon populations. That could start to change as early as 2022, when four dams are likely come down on the river — the biggest dam-removal and river-restoration project in history. Dam removal is expected to help solve many, but not all, of the river’s challenges, and understanding the change that does happen is crucial to planning the next steps for improving the river’s health.

With so much at stake, scientists like Genzoli are rushing to gather as much baseline data as they can about conditions that exist today, from sediment to stoneflies to salmon. They need to know what’s there so that in the months and years following the dams’ removal they can track the river’s changes — what happens to fish, food webs or water quality? What happens when reservoirs become rivers again and when salmon get a chance to reach their upstream limits for the first time in a century?

And perhaps most importantly: What lessons from the largest-ever dam-removal project can we apply to future efforts on other rivers in the United States and around the world?

“It’s a huge opportunity to learn about what dams do to rivers and what taking them out can also do,” Genzoli says.

But making the most of this grand scientific experiment will require time and a big infusion of money, something that many researchers worry is in short supply.

A River Upside Down

A team from the U.S. Geological Survey arrives to Happy Camp at the same time as Genzoli, and she drops in on their evening downtime, which involves bowls of homemade chili and animated talk about how they’ll help sort out one of the biggest challenges in dam removal — what happens to the sediment.

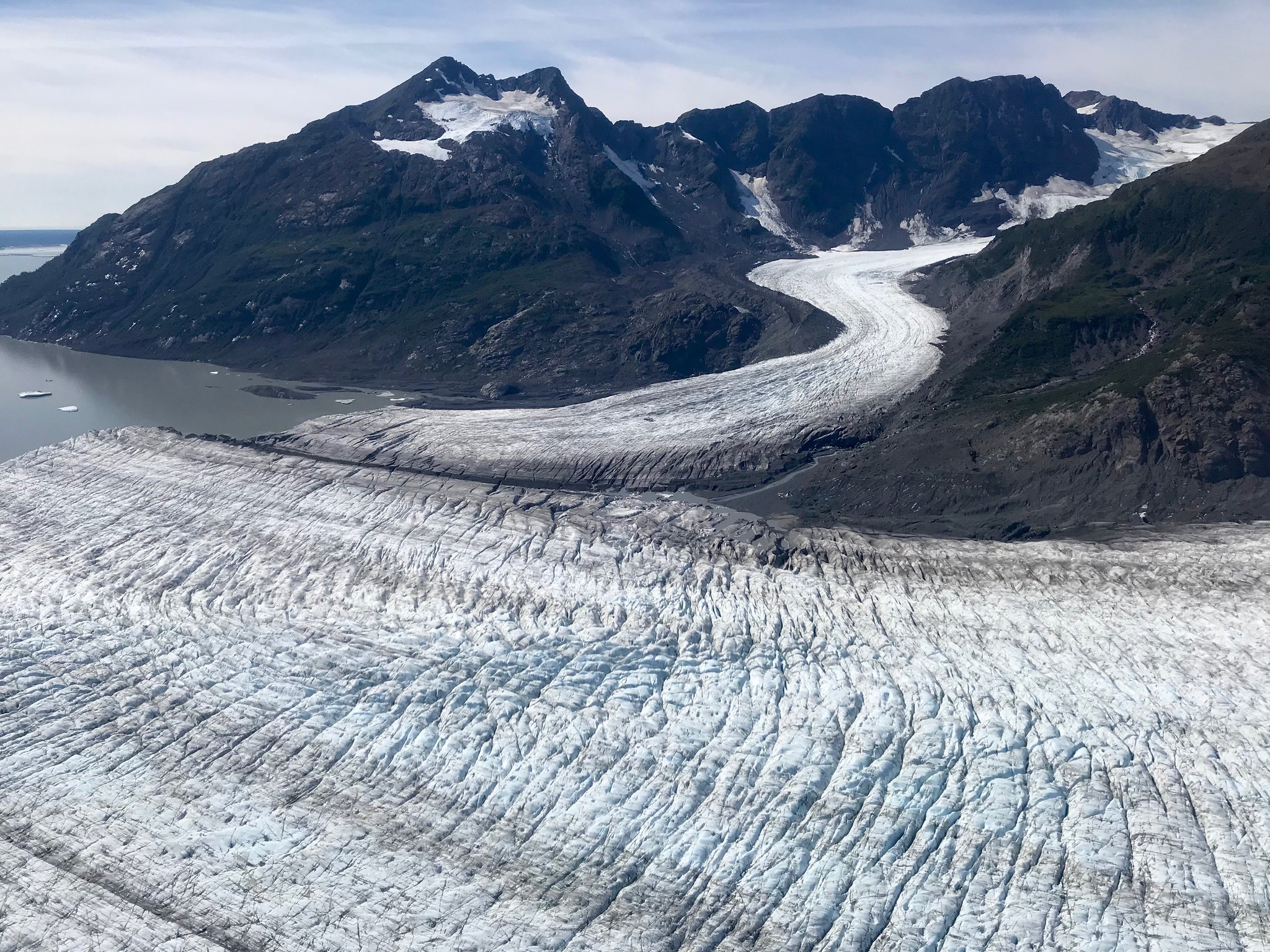

Free-flowing rivers are always washing sediment downstream, but a dam blocks that process. Restarting that flow by taking out a dam (or several) opens up a big concern: What happens to the sediment that’s been accumulating behind the barrier for decades?

It’s not a small question. The removal of the Elwha dams in Washington, the previous record for biggest dam-removal project, unleashed an astonishing 20 million tons of sediment into the surrounding environment.

Before USGS researchers can understand what will happen when the Klamath dams are removed, they need to determine what kind of sediment exists in the river now, how it typically moves, and how much additional sediment washes into the river from its tributaries. The composition of the sediment matters, too. About 85 percent of what’s built up in the reservoirs is fine material — particles smaller than sand. That’s much different than other large dam removals, like those on the Elwha, which had a lot of gravel and cobbles.

“On the Elwha we saw a lot of sediment sitting on the riverbed for months to a couple of years,” says Amy East, a USGS research geologist who worked extensively on the Elwha dam removal. “We expect on the Klamath that a lot of what sediment does come downstream will flush out really quickly.” That speed could mean fewer changes to the shape of the river from new sediment deposits in gravel bars and a shorter period of time when the flurry of material pulsing downstream would disturb aquatic life.

The task of determining what scientists call a river’s “sediment budget,” though, is not easy, especially for such a large, complex and unusual river as the Klamath.

While most rivers begin high in the mountains and become more tame (and often more polluted) as they head downstream through agricultural and urban areas, the Klamath does the opposite.

It’s so unusual that experts have dubbed the Klamath “a river upside down.”

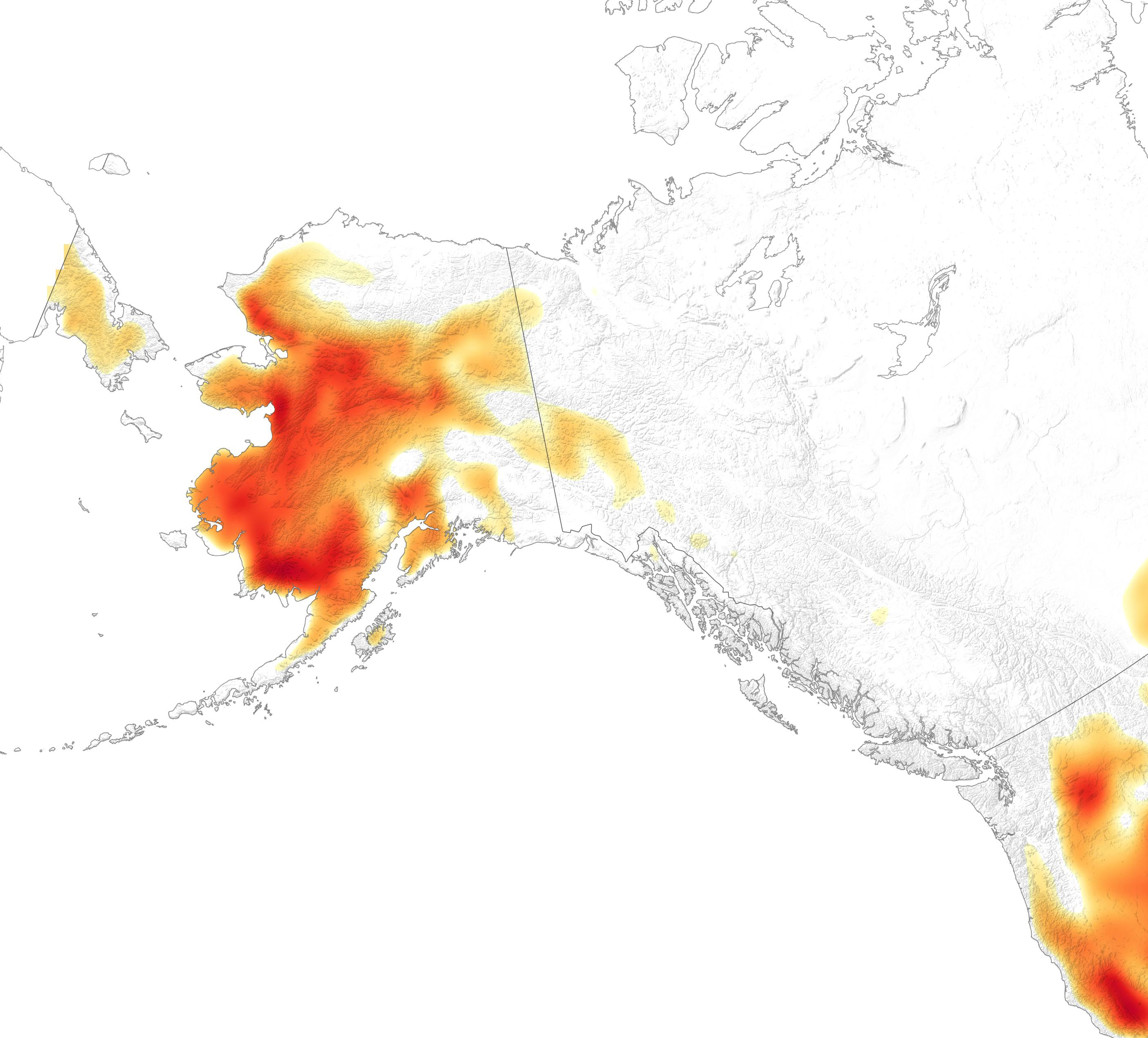

It begins its 250-mile journey in arid south-central Oregon, near the town of Klamath Falls, where flat farms and ranchland stretch to the heels of the Cascades. As it drains from Upper Klamath Lake, the river heads south and passes through irrigation canals and a 60-mile gauntlet of six dams — Link River, Keno and J.C. Boyle in Oregon, and then, after it dips across the California border, Copco 1, Copco 2 and Iron Gate. The lower four, all of which are hydroelectric, are the ones slated for removal.

After Iron Gate the Klamath finally gets a chance to behave like a river. It flows naturally through a crooked 190 miles, narrowing into tight and rugged canyons as it passes through the Klamath Mountains, finally spilling into an estuary at the mouth of the Pacific Ocean 20 miles south of Crescent City.

To understand sediment transport and other questions along this long and varied watershed, USGS researchers like the ones visiting Happy Camp need to employ a host of tools.

First, they’ve set up a network of stations in the mainstem and tributaries where they take key measurements, including stream flow. Then they take samples along a cross section to get a concentration of the sediment that’s in that water.

Every 15 minutes sensors also record the turbidity of the water — a measurement of the clarity of the water, which correlates closely with the amount of suspended sediment. The higher the turbidity, the cloudier the water appears. All of this helps them to figure out the overall load — the amount of sediment traveling over a given time period.

So far they’re up and running at a handful of sites but will add more in the future, says Chauncey Anderson, a hydrologist and water-quality specialist for the USGS Oregon Water Science Center.

He’s out on the Klamath for field research, watching from a distance as a colleague flies a drone overhead, whirling along in a lawnmower pattern above a bench of small rocks along the river. It’s dry here now, but come winter higher flows may submerge parts of this area. The drone will help map the sediment and its various sizes — distinguishing a grain of sand from a cobble.

After that Anderson and his colleagues will “ground truth” the drone’s accuracy, picking through the rocks in select sample areas and recording their sizes.

They’ll conduct this detailed mapping work in key spots along the river, and at least once more before and after dam removal, to measure the changes in the thickness of the sediment.

The drone work complements other mapping efforts employing a range of cutting-edge technologies. USGS already helped fund a flight over the entire length of the river that used Light Detection and Ranging, or LiDAR — a remote-sensing method that uses beams of light pulses to measure distances. And the Army Corps of Engineers and the Yurok Tribe — one of several tribes that call the Klamath watershed home — have already conducted a boat-based bathymetric survey, which essentially creates an underwater topographic map from Iron Gate Dam to the Pacific.

The combination of LiDAR flight data with the bathymetric boat data will provide a high-resolution map of the water above and below the surface, allowing for a three-dimensional model of the whole river.

“We can use that, and along with our intensive surveys in places like this, to detect finer scale changes than we’ve been able to do before,” says Anderson.

The USGS researchers hope to conduct those surveys again multiple times after dam removal to track how the river has changed — something nearly impossible to accomplish just a few years ago.

“The technology has advanced a lot and we’re in a position to do some stuff that people haven’t been able to do before on such a big scale,” Anderson adds.

A Productive River

While the USGS flies drones and measures rocks, about 30 miles away Genzoli takes a short kayak upriver to retrieve one of her dissolved oxygen sensors dangling from a branch and submerged beneath the river’s current. After returning to the bank, she takes a toothbrush from a zipper pocket in the front of her life vest and gives the sensor — which looks like about the size and shape of pool thermometer — a good scrub.

It’s been two weeks since she last pulled the instrument from the water, and already a green film of algae has begun to adhere to its waterproof casing.

The slimy goop doesn’t surprise her. The Klamath is notorious for being a really “productive” river — it has high rates of photosynthesis and can produce lots of algae and other aquatic plants. The abundance comes in part from upstream nutrients like nitrogen washing off of agriculture fields and runoff from the phosphorus-rich Cascade Mountains. But the effects of both are supersized by the loss of wetlands that once helped filter those nutrients before entering the river.

And when you add those nutrients to pools of warm water collecting in reservoirs behind the dams, it creates huge blooms of algae, some of which are toxic and potentially deadly to fish and other wildlife, humans included. One particularly dangerous algae species, Microcystis aeruginosa, secretes a toxin called microcystin that can cause everything from headaches to liver damage and has prompted public-health warnings in the Klamath basin during summer months.

“When you take a free-flowing river and you turn it into a large nutrient-rich bathtub, you’ve just created the ideal conditions for this kind of algae,” says Susan Fricke, water resources coordinator with the Karuk Tribe, whose ancestral territory includes Happy Camp and many other areas where researchers are active on the river.

Fricke points out that what happens in the reservoir doesn’t stay in the reservoir.

“It then discharges into the river below and goes through Karuk aboriginal territory and then down to Yurok territory,” she says. The toxic algae can travel 180 miles down the river in just a couple of days, creating an ecosystem and public-health threat.

The Karuk and Yurok have monitored water quality, including dissolved oxygen, on the river for years — data that Genzoli has also incorporated into her own research. High rates of photosynthesis from the ever-productive Klamath River cause big swings in dissolved oxygen, and that in turn can stress out fish or even kill them — even when the algae being produced isn’t toxic.

This summer Genzoli spent three weeks swimming around in a snorkel mask and flippers to look at what’s growing beneath the surface of the water. She surveyed the amount and kinds of rooted aquatic plants and filamentous algae, the kind of algae that threads together like mesh. This stuff isn’t toxic, but it’s still important to understand how it affects the ecosystem.

“Previously we didn’t really have an inventory of how widespread aquatic plants are in the river,” she says. Collecting that baseline data was one goal.

She’s also working to better understand how the kinds of aquatic plants in the river affect the rates of photosynthesis, and in turn, water quality — a key aspect in restoring the river.

Return of the Salmon

Genzoli hopes her research can also provide some insight into aquatic food webs, because one of the biggest drivers of dam removal on the Klamath is restoring healthy native fish populations.

The river was once the third largest producer of salmon on the West Coast, which helped support tribal communities and a robust commercial fishing industry. Now most of the runs of anadromous fish — species that make their way from the river to the ocean and back like Chinook salmon, coho salmon and steelhead — have declined significantly. The construction of dams that lacked adequate fish passage blocked these oceangoing fish from reaching hundreds of miles of upstream habitat. The warm water created by the dams led to the proliferation of fish disease, including the lethal pathogen Ceratonova shasta, and harmful algal blooms, further imperiling fish runs. As a result some runs are no longer commercially fishable or are curtailed. Klamath coho are even listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

The removal of the lower four Klamath dams is expected to aid the recovery of these species, so scientists are gathering key baseline data related to native fish.

Darren M. Ward is a professor in the Department of Fisheries Biology at Humboldt State University, an hour south of where of the Klamath spills into the Pacific Ocean. Ward and his graduate student Max Ramos have been clambering through hillsides clad in poison oak and, last year, study areas engulfed in wildfire smoke, to conduct research on tributaries of the Klamath River above Iron Gate dam.

They’re conducting habitat surveys to try to locate sites that would make good rearing habitat for coho salmon once the dams come out.

“Identifying the places where they’ll be able to recolonize and hopefully expand their populations is pretty important,” he says. “It’s not very often you have the opportunity to do an assessment like that, where the species isn’t around, and then directly test it in a couple of years when the dams come out.”

While salmon aren’t in these creeks now, other fish still swim their waters — and Ward is surveying the resident fish communities to see what’s out there and how many there are.

He’s also examining how those fish deal with new neighbors — other fish species that might arrive in the same habitats.

“With that baseline data, we’ll be able to see how the fish communities change after salmon come back,” he says.

Another big change with returning salmon could define the future productivity of the Klamath and its denizens. When the fish return to the river post dam-removal, they’ll arrive with bodies full of marine-derived nutrients from living and feeding in the ocean. And when they eventually travel upstream to spawn and die, their carcasses will provide a boost of nutrients to the ecosystem for the first time in a century. This will be especially helpful in tributaries that are minimally impacted by human development and low in nutrients.

“That’s essentially lots of fertilizer that’s deposited in those streams,” says Ward.

To better understand that process, he’s working on collecting data on the current nutrient composition of local organisms, including different kinds of vegetation and insects. “Hopefully we’ll be able to see how these things change once we get a new source of nutrient inputs coming in,” he adds.

Another area of study involves what happens to Chinook and steelhead. Larger than coho, those fish are expected to explore even further upstream and into tributaries in the upper watershed in Oregon above Upper Klamath Lake.

Bob Paglucio, a marine habitat resource specialist for the NOAA Restoration Center, is looking at habitat in the tributaries above the dams — Shovel Creek, Fall Creek, Jenny Creek, Spencer Creek and Hayden Creek — where Chinook and steelhead may recolonize and seeing how that habitat could be improved for the fish.

“The last thing we want to do is take down these dams and have the fish go to some habitat that’s degraded and won’t support them throughout their lifecycle,” says Paglucio.

Dam removal will mean different things in different parts of the watershed. The area now between the four dams will change the most as lakes become free-flowing rivers again. That could have big impacts on the native fish that currently reside there.

“The species that have keyed into that particular life history, like some of the redband [rainbow] trout, are going to have a different life history,” says Paglucio. But Mark Hereford, the fisheries reintroduction coordinator for the Klamath district of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, doesn’t see any negative impacts for native fish that are already living there.

“Our resident trout, they’re actually probably going to be more competitive against steelhead trout just because they are residents here,” he says. And it’s possible the two fish could interbreed, says Ward. Despite their different names they’re actually the same species — just with different life histories. Steelhead are anadromous and rainbow trout remain in the river.

But for non-native species, it could be a different story. Fish such as carp, sunfish, and large-mouth and small-mouth bass thrive in slow, warm water — conditions that will likely disappear with dam removal.

“I think once the dams come out and those reservoir habitats aren’t available, those non-native fish are mostly going to go away,” adds Ward. That could further improve conditions for native species by removing competition for food and other resources.

Downstream Effects, Mind-blowing Science

The fish efforts don’t end there.

Robert Lusardi, a research scientist at the University of California, Davis and a cold-water fish scientist for the nonprofit California Trout, is hard at work studying parts of the river and its tributaries below Iron Gate Dam.

He’s teamed up with the Yurok Tribe to study changes in fish assemblages — looking at how native fish and non-native fish are currently using the river, what habitat they’re occupying and where juvenile salmon are rearing.

He’s also an expert in aquatic insects, which have rapid life cycles and can be good indicators of changes in the ecosystem. By looking at what happens to mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies — for example, after a disturbance such as a rapid change in water temperature, flow or sediment — he can determine how the aquatic ecology is responding. All of that will be useful when the dam removals create a really big change for the river.

But what excites Lusardi most is a new research endeavor in collaboration with Rachel Johnson, a pioneering fisheries biologist with NOAA. They plan to better understand fish movement by studying fish ears — or a part of them.

Otoliths are a piece of calcium carbonate in the inner ear of fish which keeps a record of a rare element, called strontium, that’s found in the water. Different parts of the river, and different tributaries, have different values of strontium in the water.

“If there’s a difference there, then the fish that rear in those locations will incorporate those different strontium values into their ear bones,” explains Lusardi. When an otolith is pulled from a fish, scientists can understand its life history by seeing the changing strontium values and better understand where it traveled in the watershed.

This research for the Klamath is in its early stages, the scientists were just awarded funding to determine strontium values throughout the watershed. Their goal is to look at where juvenile salmonids are currently rearing below their current stopping point at Iron Gate Dam and track how that will change with dam removal as historical habitat is recolonized by salmon post dam removal.

“If it all works out, it will be mind-blowing,” says Lusardi. “It’s one of the coolest kinds of science I think I’ll be able to work on in the Klamath.”

Uncertain Future

The size, complexity and relative remoteness of the Klamath River watershed have created a need for cooperation among the scientists who work out there.

“No one has the capacity to cover all of the areas,” says Fricke. “That’s why we do best when we work in teams and we work collaboratively.”

That cooperation has become increasingly important because efforts to fund all of this scientific research and habitat restoration have been piecemeal so far.

That’s because the process of paying for the dam removal is almost as convoluted as the river itself.

The dams themselves are owned by PacifiCorp, which realized, when facing the environmental headaches the dams created, that it would be in their best financial interest to remove them.

But they aren’t the ones doing the removal. Instead the company will pass off its license to operate the hydroelectric dams to a newly created entity, the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, which will then oversee the removal and restoration.

This new corporation has $450 million to do that work, but that financial pot only includes funding for scientific inquiry directly related to ensuring dam removal doesn’t violate provisions of the Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act or other environmental laws.

Understanding how the river changes with dam removal and what that means for the ecosystem isn’t part of the package.

“I mean, this is the largest dam removal effort in the world — it would’ve been great to have guaranteed funding,” says Fricke.

In part, that’s because the dam removal isn’t being driven by any kind of congressional mandate — in fact, just the opposite.

“What we have right now is not the big dream that we all had several years ago when we put together the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement,” says Paglucio. “That was a huge package to remove the dams and do extensive [environmental] restoration, but it never made it through Congress.” Instead dam removal and restoration will be funded by $200 million from PacifiCorp’s ratepayers in Oregon and California, and $250 million from Proposition 1, a water bond passed by California voters in 2014.

As a result scientists have resorted to stitching together money from existing grant programs, but Paglucio says “there’s no big wave of funding like we originally hoped there was going to be.”

And while agencies like the USGS and NOAA are still conducting research, the lack of federal support has placed them in a backseat position, unlike the earlier Elwha dam removal project, where federal agencies helped drive the process. This time around “we’re just studying the effects of someone else [doing] a dam removal,” says East of the USGS.

And there’s one other problem — the timeline for removal has been a bit of a moving target. Right now it looks like the dams will come down in January 2022, but some regulatory hurdles still need to be cleared, including a water quality permit from California and the official transfer of the license from PacifiCorp to the Klamath River Renewal Corporation by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which oversees the licensing of hydroelectric dams.

That means that dam removal isn’t officially a done deal yet, which is delaying research initiatives, and likely, funding.

“I think people right now still view it as a risky research investment because there’s the potential that we could gather all this baseline data and it might not come to fruition any time soon,” says Ward. “But as the regulatory and policy side of it moves forward and it becomes clear that the dams are actually, definitely going to come out, then I think there’ll be more investment.”

But even if that happens, Genzoli points out that gathering adequate baseline data isn’t something you can do quickly.

“The problem with waiting is that there’s so much variation in how a river works year to year,” she says. “You can’t just study the river one year before dam removal and one year after and say this is how it’s changed.”

For Genzoli, a lack of funds means that much of her work is on shoestring budget — supported by grants to her advisor and propelled by her willingness to sleep in the back of her car while out on research expeditions.

Despite the hardships, the opportunity to be on the front lines of a scientific endeavor of this magnitude is too important to pass up. And while no one is under the illusion that the removal of the four dams will return the Klamath to pristine conditions, the expected changes are still likely to be profound.

“Dam removal won’t be the end of restoring this river, but we will be able to see what it helps and what it doesn’t,” she says. “It’s likely to achieve two major goals — restoring fish passage and getting rid of these toxic algae blooms — but there’s a billion other things it’s going to influence, too, that would be good to understand.”

![]()