You never know what hidden truth may lurk in the background of a photograph.

John Amos learned that lesson more than 20 years ago, when he was working as a consulting geologist in Washington, D.C. There, a poster-sized image hanging on the office wall showed a satellite photo of Mount St. Helens taken about 10 years after its famous 1980 eruption. Most people looking at the photo were struck by the visible destruction caused by the blast and lava flows. But what grabbed Amos’s attention was another even larger area of destruction in the surrounding national forest, which bore the distinctive checkboard pattern of clear-cut logging.

“I didn’t really realize how our national forests were being managed,” he says. “And when I saw that the devastation from clear-cut logging greatly exceeded this apocalyptic, natural event … that was so stunning.”

That image stayed with him, along with others he saw over the years as a consultant for industry projects, including oil and gas drilling.

The mounting destruction of the landscape finally led Amos to take a big leap: In 2001 he left his well-paying D.C. job to start SkyTruth, a nonprofit aimed at harnessing the power of satellite imagery to inspire environmental protection.

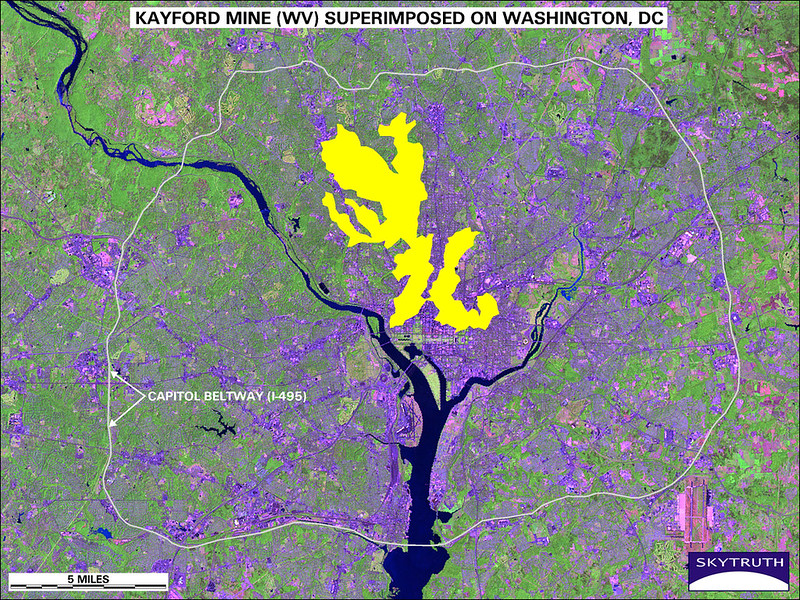

Along the way SkyTruth has left its own big mark, using imagery, data and mapping technologies to reveal the true scale of oil spills like the Deepwater Horizon disaster and blow the whistle on a 14-year-long leak in the Gulf; to track the growing footprint of mountain removal mining in Appalachia; to monitor global fishing operations; and to bring greater transparency to the fracking industry.

The organization’s research has driven scientific studies, uncovered corporate and government malfeasance, and helped activists put a picture on their cause.

Nearly 20 years later the mission of SkyTruth hasn’t changed, but the available technology has vastly improved. So, too, has the potential to use these eyes in the sky to boost conservation and research efforts.

We spoke with Amos about the power of images, the next technological frontier and how ordinary people can begin “skytruthing.”

A big part of your work depends on satellite imagery. How do you access those images?

There are satellites producing data that’s free for the public to access. And then there are satellites that have other capabilities that are operated commercially, where you have to pay for the data.

Luckily, one of the unsung great successes of the American space program was the launch of the Landsat series of earth-imaging satellites beginning in 1972. That has produced a tremendous body of images, although there have been times when it wasn’t really available to the public. During the late 1980s through the mid-1990s, as a consequence of the Reagan administration’s push to privatize government assets, they took the Landsat program data and gifted it to a private company. The data went from costing something like 30 or 40 bucks an image to $4,400. When I started doing this work, all but the biggest environmental groups were priced out of that technology.

Luckily that situation’s changed over the years. Now it’s all available for free. And in fact, as soon as it became available for free, Google downloaded all the Landsat satellite images at the time and made them publicly available. And then the European Space Agency has a tremendous earth-observation program, too. And their data is available for free.

But a lot of the work we do requires higher-resolution images than the ones that are publicly available. In some cases we’ve been able to get imagery gifted to us by the companies that operate those satellites so that we can demonstrate the kinds of things you can do with their imagery.

There’s so much that your organization has done with research and data, but the key mission all along has been focused on imagery. Why?

My initial motivation for starting SkyTruth was to produce pictures and give pictures away. You know, a picture’s worth a thousand words, seeing is believing, right?

I think images have the power to hit people at a brainstem level. So, rather than just hitting people over the head with well-documented reports, full of data about the impact of deforestation in Papua New Guinea, for example, show ’em a picture of what that looks like.

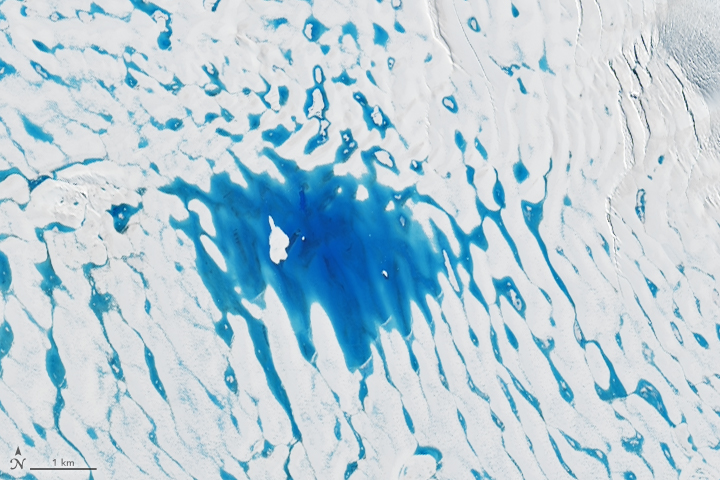

And because of this longtime series of earth-observation imagery that’s available, we can do time travel. We can show people what “normal” used to be, and what things look like now — and in some cases, project into the future.

That’s a really powerful tool because of this shifting baseline problem that we have. What we think of as normal is what’s around us right now, but a place could have been totally different 10 years ago. And people forget that. So showing that change is a powerful aspect of the imagery.

And over the years, tools have come along that have just exploded our ability to do that kind of visual presentation to people. One of the biggest ones was Google Earth. I just remember being amazed that I had imagery of the whole world at my fingertips and in a lot of places, very high-resolution, detailed imagery.

There can be a big gap between people getting information — or in this case, imagery — and actually taking action. How do you close that gap?

Producing unique data sets from imagery that are well documented and scientifically robust has become an increasingly important part of what we do. And it’s becoming increasingly doable with the advent of cloud-computing platforms.

One example is we use the Google Cloud platform that absorbed the millions of Landsat satellite images. We’ve built a process that analyzes those images once a year and creates a map of all of the land in Appalachia that’s actively being impacted by mining.

And then we create a companion geospatial data set that anybody with any mapping skills can download and use. We give that away for free. I think seven or eight peer-reviewed studies have been done using that data set. One of them resulted in a legal action that went all the way up to the Supreme Court. There’ve been studies of not only environmental impacts, but human health impacts.

It’s our hope that there’s enough rational people in the world that science will still move the public policy needle occasionally in a positive direction.

We also don’t want to feel like we have to cover the whole planet all the time. So for anybody who’s interested or so inclined, we try to be public and open about the tools we use. And we point people in directions where they can start “skytruthing,” too.

One of the key tools for that is the SkyTruth alerts system, which is an interactive map where we publish environmental information that is timely and alert-worthy. People can sign up to get a notification anytime a new alert pops up within their area of interest. We’re hoping someday they can create their own reports and soon they’ll be able to create their own alert and publish it back into our system for anybody to see.

What are you focused on now?

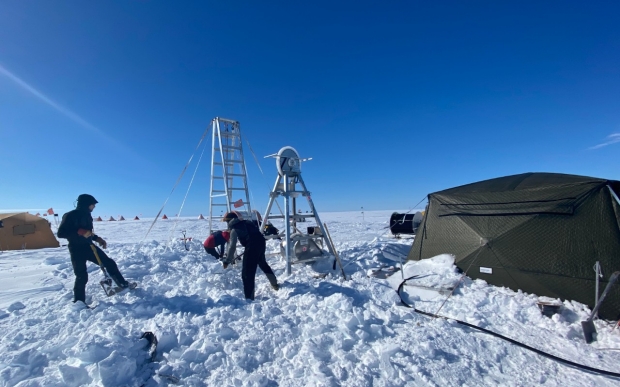

Our organizational focus right now is applying machine learning to detect meaningful patterns in imagery and patterns in space and time.

We’re very excited by our continuing strong partnership with Google. They’ve been so helpful to us in being able to do really big projects, and now we have a new partnership with Amazon Web Services to use machine learning to automate the detection of oil pollution at sea.

We’re to the point where we’ve got a working prototype that we’re going to deploy this summer to be able to look at the whole ocean instead of just what a few interns can manage to do in a couple hours. That’ll open doors to a lot of other environmental monitoring opportunities.

As the satellite imagery constellations get better and better, and the prices come down, we will get access to imagery that is more detailed and capable. With that we’ll be able to notify people not only that we think something happened, but what we think it was, how big and bad it was, and when it happened.

What else do you see in the future of conservation with this kind of technology?

In conservation we’re heading toward near real-time surveillance of areas of high conservation value or environmental concern.

We have a new partnership with the Wildlife Conservation Society to work with them to figure out how to apply artificial intelligence-driven analysis of satellite imagery to better monitor enforcement and management of protected areas around the world — onshore and offshore.

Meet Cerulean — SkyTruth’s new project to automate the detection of #bilgedumping at sea by cargo vessels and tankers. https://t.co/6pIe0o3Ope

— SkyTruth (@SkyTruth) May 5, 2020

But we still have the problem that you described, which is that you can now see in real time that there’s chainsaws cutting down trees in that orangutan reserve. But what are you going to do about it?

And that’s the question that is going to be harder to answer.

Protected area managers might not yet be geared up to be able to take action on a real-time alert. But I think as people realize that they can know that there is illegal logging happening that day, then they’re going to build a program around taking action based on that knowledge.

In the early days of our Global Fishing Watch program, people would say, “Oh, you’re going to bust the bad guys, right?” Well, no, of course we don’t have enforcement vessels on the water.

But by making all this fishing activity visible, we’re creating space for new ways to manage national waters and high-seas fisheries, and new ways to measure what’s happening out there and model the impact on ecosystems.

It brings to light a whole area of activity that creates all these new opportunities for science, research, regulation and management. But it also opens a big window for consumers who more and more want to know that the dollars they are spending when they buy fish are not supporting a company that uses slave labor on their fishing vessel fleet or is not doing environmental harm.

So I think in addition to possibly providing better enforcement by government agencies, there may be an even bigger potential in shifting society’s attitude toward that problem in a way that businesses have to respond to.

![]()