This story was originally published by NM Political Report.

A new paper looking at the health impacts of flaring in the Bakken area of North Dakota found that people 60 miles away can experience respiratory distress because of flaring. The impacts have significant economic effects that should be considered in regulatory policy, the researchers said.

The lead author, Wesley Blundell, said these impacts could be even more pronounced in the Permian Basin in Texas, where flaring in 2020 was greater than the flaring in the Bakken during the study time period and population density, at least in west Texas, is greater than in North Dakota.

Blundell is an assistant professor at the School of Economics at Washington State University and said he approached the topic largely from an economic perspective, including placing a dollar value on the public health impacts of flaring. This estimated dollar impact is based on the amount of natural gas flared.

The study was published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Public Economics. Blundell said he accessed proprietary hospital data and looked into the hospitalizations for respiratory illness. He and his co-author also gathered the GPS locations of wells and monthly flaring reports from those sites.

“We were able to start really digging into what the relationship was and how big the relationship was between the flaring of this unprocessed natural gas and all the contaminants that come with it and the respiratory health of the individuals who live up to 60 miles downwind,” he said.

They found that an increase in flaring of 1% can lead to a 0.73% increase in hospitalizations. In North Dakota, the study found an increase of 11,000 hospital visits. The time period examined was early in the Bakken boom from 2007 to 2015.

The New Mexico Oil and Gas Association states in a report that flaring is done in an “attempt to eliminate potentially unsafe, flammable vapors and to destroy unwanted emissions of methane and [volatile organic compounds.]”

The reason behind flaring is usually safety concerns or transportation constraints, the organization states. NMOGA further states that the alternative to flaring is often venting, which leads to more emissions.

Flaring also occurs after a well is completed because the natural gas that is initially produced can’t be handled by the production facilities as it includes flowback, or components from the fracking process like sand.

Lack of infrastructure capacity, including pipelines to transport the natural gas, can also lead companies to flare natural gas.

Blundell said his study did not look at why the companies were flaring natural gas, but he said that is something that needs to be examined.

New Mexico

Barbara Webber, executive director of Health Action New Mexico, said there is a lack of data in New Mexico, but that the state does have high asthma rates and the oil producing region in the southern part of the state has high rates of hospitalization due to asthma. She said she expects that the findings of the North Dakota study would hold true in New Mexico as well.

Respiratory illness is only one of the health impacts associated with the oil and gas industry, Webber said. She highlighted studies finding links to cancer as well as preterm and low-weight births, which tend to be more common in New Mexico than in many other states.

Under Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, regulations have been promulgated to address flaring and emissions from oil and gas.

“We’re excited to see that hopefully there’s going to be more oversight and inspection,” Webber said.

At the same time, the Legislature did not fully fund the Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department’s request and New Mexico has a low ratio of inspectors to ensure that companies are complying with regulations, Webber said.

New Mexico has regulations in place to address flaring, including the natural gas waste rule adopted last year by the Oil Conservation Commission. This rule required companies to capture 98% of methane emissions by the end of 2026. The first quarterly reports were due Feb. 15. Just three days after that deadline, EMNRD’s Oil Conservation Division published a list of operators who failed to comply on its compliance website and provided notices to more than 400 operators.

According to information provided by EMNRD, some of the operators notified reached out to the OCD and the division has worked with them to rectify problems and answer questions. As a result, 158 of those operators were able to file, thus achieving compliance with the requirements. EMNRD reports that the operators who have filed those reports represent nearly 99 percent of the produced gas in the state and 88 percent of wells.

On March 10, the OCD issued five notices of violation as well as civil penalties to operators who failed to file the report required by the new rules.

Clean Air Task Force Study

Another recent study done by the environment-focused non-profit Clean Air Task Force in coordination with Rice University found that flaring of natural gas contributed to between 26 and 53 deaths in 2019. This study, which was published in the peer-reviewed journal Atmosphere in late February, looked at black carbon, or small particulate matter produced through flaring.

Lesley Fleischman, a senior analyst at Clean Air Task Force and one of the authors, said that Texas, North Dakota and New Mexico had higher levels of mortality associated with flaring. She said the researchers used satellite imagery as well as modeling.

“The problem is pretty clear that there’s a health impact concentrated in areas where flaring is occurring,” Fleischman said, adding that the health impacts are unnecessary.

Clean Air Task Force is pushing for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to pass regulations ending the practice of routine venting and flaring. While New Mexico has regulations in place to address flaring, including the natural gas waste rule adopted last year by the Oil Conservation Commission, neighboring states like Texas do not necessarily have the same level of regulations. Having EPA rules in place would protect New Mexicans from health impacts from flaring that occurs out of state, she said.

“Flaring is a waste of a resource, a valuable resource and it’s causing pollution and there’s no reason for it,” she said.

Marginalized Communities

Marginalized communities, such as minorities and low-income households, often bear a larger share of the pollution burden. Webber gave the example of Native Americans in northern New Mexico who live close to oil and gas development.

These health impacts can lead to reduced work days, children missing school and increased medical expenses. Webber said these impacts can keep people in poverty.

Typically, Blundell said, people think that those most impacted by oil and gas are the people who are also getting the economic benefits from that development. But, in the case of the Bakken, he said that is not necessarily true. This is one of the things he said surprised him the most while doing the study. He said 50 percent of the impacts from flaring were in areas where 20 percent of the resources were extracted.

“Those who are bearing the environmental impact aren’t necessarily those who are getting the economic benefit,” he said.

© NM Political Report

Previously in The Revelator

States Take Action to Curb Oil Industry’s Most Glaring Problem

These are the times that try our souls — and our Facebook feeds.

These are the times that try our souls — and our Facebook feeds. The Intersectional Environmentalist: How to Dismantle Systems of Oppression to Protect People + Planet

The Intersectional Environmentalist: How to Dismantle Systems of Oppression to Protect People + Planet Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet

Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet Effective Conservation: Parks, Rewilding and Local Development

Effective Conservation: Parks, Rewilding and Local Development Endangered Maize: Industrial Agriculture and the Crisis of Extinction

Endangered Maize: Industrial Agriculture and the Crisis of Extinction Was It Worth It? A Wilderness Warrior’s Long Trail Home

Was It Worth It? A Wilderness Warrior’s Long Trail Home Ecoart in Action: Activities, Case Studies and Provocations for Classrooms and Communities

Ecoart in Action: Activities, Case Studies and Provocations for Classrooms and Communities The Bald Eagle: The Improbable Journey of America’s Bird

The Bald Eagle: The Improbable Journey of America’s Bird

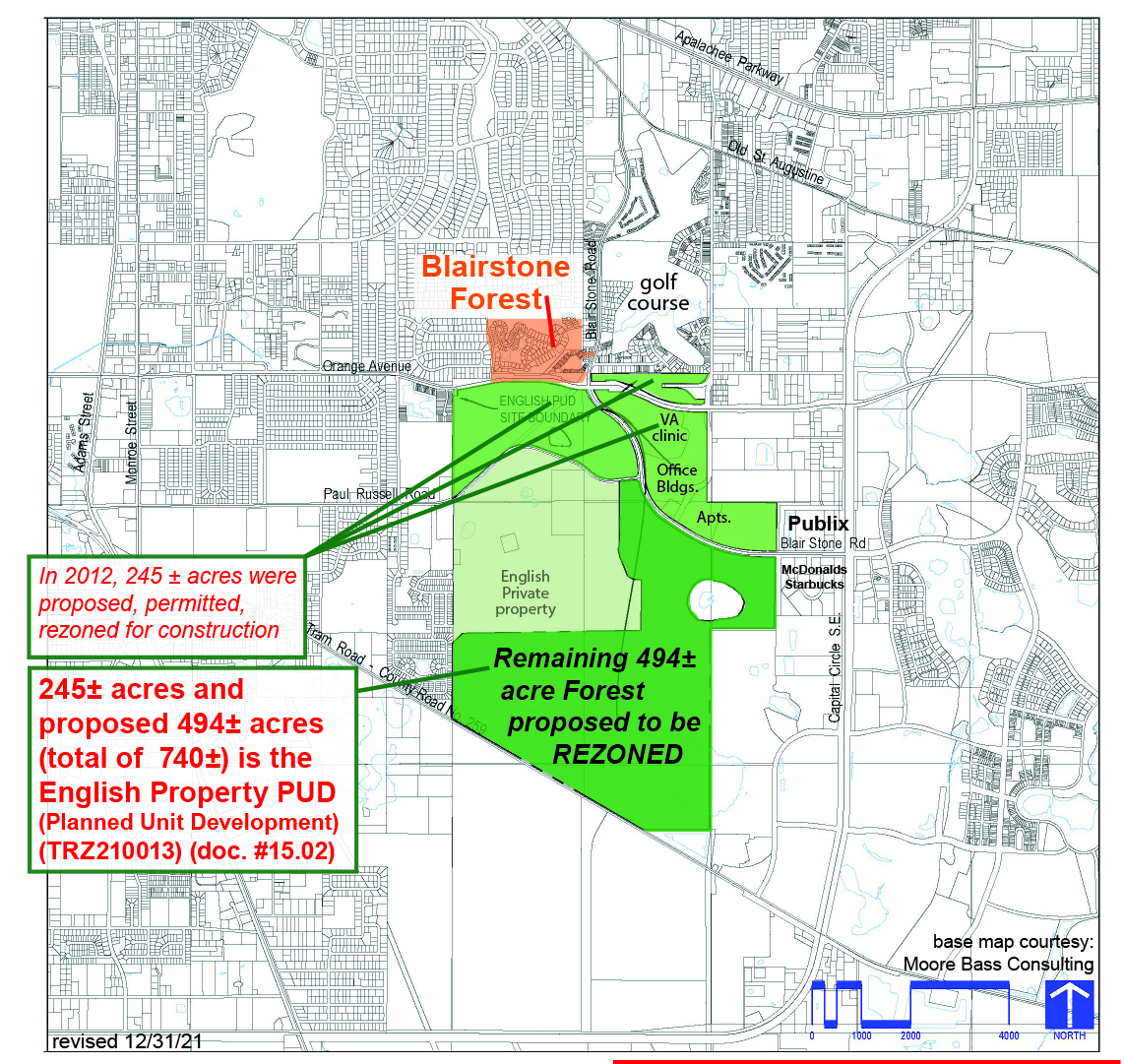

An unprotected 740-plus-acre hardwood forest in southeast Tallahassee, Florida, called the English Property Planned Unit Development and PUD Amendment. This majestic upland hardwood forest, privately owned by the English family for a couple of generations, has withstood the test of time but has now become a figurative endangered species.

An unprotected 740-plus-acre hardwood forest in southeast Tallahassee, Florida, called the English Property Planned Unit Development and PUD Amendment. This majestic upland hardwood forest, privately owned by the English family for a couple of generations, has withstood the test of time but has now become a figurative endangered species.

But that’s not all: In August 2021, developers submitted an amendment to the city to rezone the remaining 494 acres of the existing English Property PUD. This would allow the realtor, developers and potential buyers of the land to construct medium-density residentials (multistory apartment complexes, single-unit homes), mixed office/commercial complexes and “neighborhood village centers” (a euphemism for gas stations, convenience stores and fast-food places), leaving a mere fraction of the property as disjointed “open spaces” with no evidence of conservation easements.

But that’s not all: In August 2021, developers submitted an amendment to the city to rezone the remaining 494 acres of the existing English Property PUD. This would allow the realtor, developers and potential buyers of the land to construct medium-density residentials (multistory apartment complexes, single-unit homes), mixed office/commercial complexes and “neighborhood village centers” (a euphemism for gas stations, convenience stores and fast-food places), leaving a mere fraction of the property as disjointed “open spaces” with no evidence of conservation easements.