A nasal, laughing bird call echoed through the Ortiz Mountains in northern New Mexico this September. A couple of pinyon jays chattered loudly as they flew over the piñon pine and juniper woodlands that sweep across the foothills. “They have really fun calls,” said Peggy Darr, then the resource management specialist with Santa Fe County’s Open Space, Trails, and Parks Program. “They’re a very hard bird not to love.”

The jays forage for piñon nuts in the dense habitat on the ridgetop in fall and winter, then cache them in more open areas near the road, she said. Caching is critical for the jays’ survival, but also for the trees. Pinyon jays and piñon pines are wholly interdependent — the piñon nuts provide essential sustenance for the bird, and the jay offers critical seed dispersal for the tree. The pinyon jay is a keystone species of these arid forests of diverse piñon pines and junipers, extending over 150,000 square miles across 13 Western states.

The “blue crows,” as the jays were once known, are year-round residents of 11 Western states, but New Mexico hosts the largest share, about one-third of their population.

Together, jays and piñon pines help create vital habitat for numerous plants and animals, including threatened bird species like Woodhouse’s scrub jay and the gray vireo. The pines also supply a traditional food source for Indigenous tribes and Hispanic communities in New Mexico.

These dusky blue birds once roamed the West in huge flocks, with hundreds alighting on piñon pines to glean nuts in the winter months. Now it’s uncommon to see flocks of more than 100. In the last 50 years, the population of pinyon jays has declined by an estimated 80%.

The jay is listed as a “species of greatest conservation need” in New Mexico, and this year the conservation organization Defenders of Wildlife petitioned to list it under the Endangered Species Act, citing “woefully inadequate” protections at the federal and state level.

The two major culprits of the jays’ decline are climate change and a long history of piñon pine removal carried out by federal agencies, including, increasingly, thinning and burning for wildfire prevention. Both have impacted piñon pines and led to declining nut production. Darr, now with the Defenders of Wildlife, said conservation is critical for the jay, but also “for an entire ecosystem, and all the other species” that depend upon it.

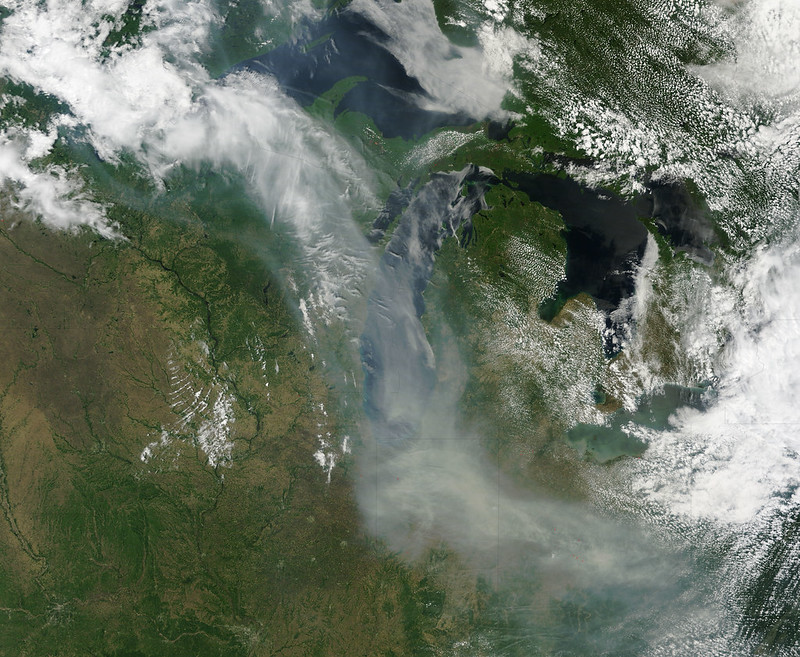

In the midst of a historic megadrought in the Southwest and a record-setting wildfire season in New Mexico, land managers are racing to implement wildfire prevention measures. Congress this year directed billions in funds to federal agencies, who in turn are planning significantly increased treatments on millions of acres of federal lands.

In forests, these treatments often involve thinning: the removal of trees by machinery, by hand, or with herbicides. While historically piñon-juniper forests were systematically cleared using destructive techniques like chaining — dragging thick steel chains between tractors to rip out trees in their path — current practices by federal agencies involve more selective thinning.

But some bird biologists, like Darr, are sounding the alarm that even today’s thinning methods degrade pinyon jay habitat. These woodlands are already under extreme drought stress, especially in New Mexico, with predictions for widespread loss due to climate change. And some studies suggest thinned piñon-juniper forests are less resilient to beetle infestation and drought.

In 2004, the International Union for Conservation of Nature placed the pinyon jay on its Red List as “vulnerable” to extinction. It cited a current rate of decline of over 3% per year, and a historic loss of “possibly millions” of jays from the 1940s to the 1960s. During roughly the same period, an estimated 3 million acres of piñon-juniper woodland were destroyed to create pasture for livestock.

Bryan Bird, the Southwest program director at the Defenders of Wildlife, said piñon-juniper woodlands have long been maligned as having no economic value, and targeted for removal by private, state, and federal managers in favor of grasses for livestock. The current management imperative calls for thinning to reduce wildfire risk, he said, “which most people think is benign” for the bird. “But it’s not,” he added, noting that the specific habitat requirements of pinyon jays are just beginning to be understood.

Kristine Johnson is a retired faculty member of the biology department at the University of New Mexico who for 20 years has studied pinyon jays and their habitat. While there’s not yet research on the direct impacts of thinning or burning on pinyon jays, Johnson said studies show “extreme thinning” isn’t good for nesting habitat.

And according to Bird, the flood of new federal funds for wildfire prevention combined with what he called a loosening of environmental rules is “not going to be good for the pinyon jay.”

New Mexico is home to four evergreen juniper species and the Colorado piñon, a small tree with short bottlebrush needles that sprout from dense branches. Woody cones tightly grasp its thick, egg-shaped seeds, drawing the garrulous jays to pry them out.

Johnson said the jays have several adaptations that make them excellent seed dispersers for piñon. Their long bills work like a chisel to crack open the tough piñon shell. Their esophagus expands to store up to 50 nuts, and since they’re highly social, one flock can plant millions of seeds in a fall season, Johnson said. They’re strong fliers with a huge range of several thousand hectares. And while they have an excellent memory for recalling their nut caches, the seeds they don’t retrieve can become new piñon trees.

But this feat of co-evolution comes with vulnerabilities. On an irregular cycle, piñon pines produce a mast crop — a particularly abundant supply of nuts. Pinyon jays rely on these mast crops for their reproduction, storing large quantities of seeds in the fall and winter to feed to their young in the spring. In a drought year without a mast crop or other bountiful food sources like insects, pinyon jays may not nest at all, Johnson said.

In recent years, Johnson has observed smaller piñon mast crops, occurring with less frequency, and studies have linked drought and declining cone production. And according to Johnson, not all piñon juniper forests provide good habitat for jays. She recently created a model based on previous fieldwork to predict nesting habitat across New Mexico, and found jays tend to place their nests in larger trees in areas with dense canopy cover and low levels of recent disturbance. Her analysis found the highest quality habitat was “surprisingly scarce.”

A new survey may provide help for jay conservation. The New Mexico Avian Conservation Partners, a state chapter of the national bird conservation coalition Partners in Flight, is surveying for pinyon jays and other birds in thinned and unthinned piñon-juniper forests across New Mexico. Darr, a co-chair of NMACP, said they started the study out of a sense of urgency. “We didn’t have time to wait for a bunch of little studies to be done to get a consensus” on how treatments affect jays, she said. Additional bird species that rely on these forests include Grace’s warbler and the juniper titmouse, both listed as “species of greatest conservation need” by the state of New Mexico.

The second season of the three-year study wrapped up this year, Darr said, and results from the first year’s data show lower densities of some birds in the thinned areas.

The NMACP this year released recommendations for piñon-juniper management, co-authored by Darr, Johnson, and others. Darr said unlike scientists in other states, she and other biologists with the NMACP “feel the science is strong enough” to recommend land managers reconsider or reduce thinning in order to conserve pinyon jay habitat.

For her part, Johnson said some agency management plans “are applied in sort of a generic way,” without taking into account historic wildfire frequency, for example. She noted the scientists’ recommendation for treatments like thinning near human infrastructure, with “less focus on altering the wild areas.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declined to make a subject-area expert available for an interview. In a non-attributed written response emailed to Undark by FWS public affairs specialist Allison Stewart in September, the agency cited “little data on the effects of management on jay populations,” and said “we are exploring the effect of the removal of pines and junipers” to reduce wildfire risk in order “to determine if these contribute to short term causes of decline.”

Johnson said some agencies are receptive to recommendations for management to conserve pinyon jays. The Pinyon Jay Multi-state Working Group, for example, recommends that thinning take place outside the breeding season, and that managers avoid thinning in habitat with nesting colonies. “But they’re huge bureaucracies and changing people’s minds takes a long time,” Johnson said.

The recent Defenders of Wildlife petition also noted the impact of rules allowing the approval of projects in pinyon jay habitat without environmental assessments. “It just gives them a path to undertaking large habitat manipulations without considering the impact on this bird,” Bird said.

The petition contains the first estimate of total acreage of piñon-juniper habitat currently treated by the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service in states with pinyon jay populations. The estimate “suggests extensive loss of suitable pinyon jay habitat on federal lands,” with over 440,000 acres impacted, according to the petition.

Bird said that’s why listing the pinyon jay as endangered is critical: “It would require them to take a really hard look at what the impacts are to the bird” and consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service before carrying out treatments in pinyon jay habitat. Johnson agreed, saying that listing the pinyon jay as endangered would have a “huge impact” because agencies would be required to alter their management plans.

Throughout history, Indigenous peoples across the West have foraged for piñon nuts and relied on them as a critical food supply during the winter and lean years. When the Spanish arrived in the Southwest in the 1500s, they also began gathering the oily, protein-rich seeds. The long tradition of families harvesting piñon nuts continues in many communities today. Yet threats to piñon forests endanger these cultural practices.

“I’ve been picking piñon since I could walk,” said Raymond Sisneros, a retired horticulture teacher who farms outside the town of Cuba and traces his family line to the first Spanish settlers.

If the pines near their home weren’t producing, his family would drive to another site. His grandfather taught him how to harvest the nuts, and he sold them door-to-door in the nearby town. Piñon wasn’t a treat, he said, but a “way of life,” a source of both food and revenue. Now it’s rare to find New Mexico piñon for sale.

The last time Sisneros had a big crop near his home was four years ago, and family members traveled from as far away as Tennessee and California to gather piñon. But those traditions may be coming to an end. “I’m scared, because our piñon forest is going,” he said. The large trees that once produced over a hundred pounds of piñon nuts are dying because of drought, he said.

Val Panteah, governor of Zuni Pueblo in northwestern New Mexico, said many tribal members gather piñon in the late fall. He remembers harvesting piñons with his family as a teenager, climbing into trees and shaking the branches so the nuts would fall onto a bedsheet on the ground.

Panteah has observed changes in piñon crops over the years. “When I was really young, it seemed like it was every year” or every other year for a big piñon crop, he said, “but now, it feels like every four years.”

The jays may offer the best hope for resilience for piñon-juniper forests. They’re “the only species that is capable of moving a woodland uphill if there’s been a fire,” Johnson says, “or replanting an area that’s been burned or decimated by insects or drought,” by ferrying seeds away from the degraded area.

Yet these species’ intimate interconnection also leads to what Johnson calls a vicious cycle. If the bird is lost, the woodlands can’t be replanted.

If the woodland isn’t replanted, the bird populations decline.

For the tree, for the bird, and for the people, she said, “it would just be tragic for us to lose these woodlands.”

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

Previously in The Revelator:

The ecological disaster that horrifies me the most is species extinction. Habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution and anthropogenic climate change are taking an unprecedented toll on us and the species we share this planet with.

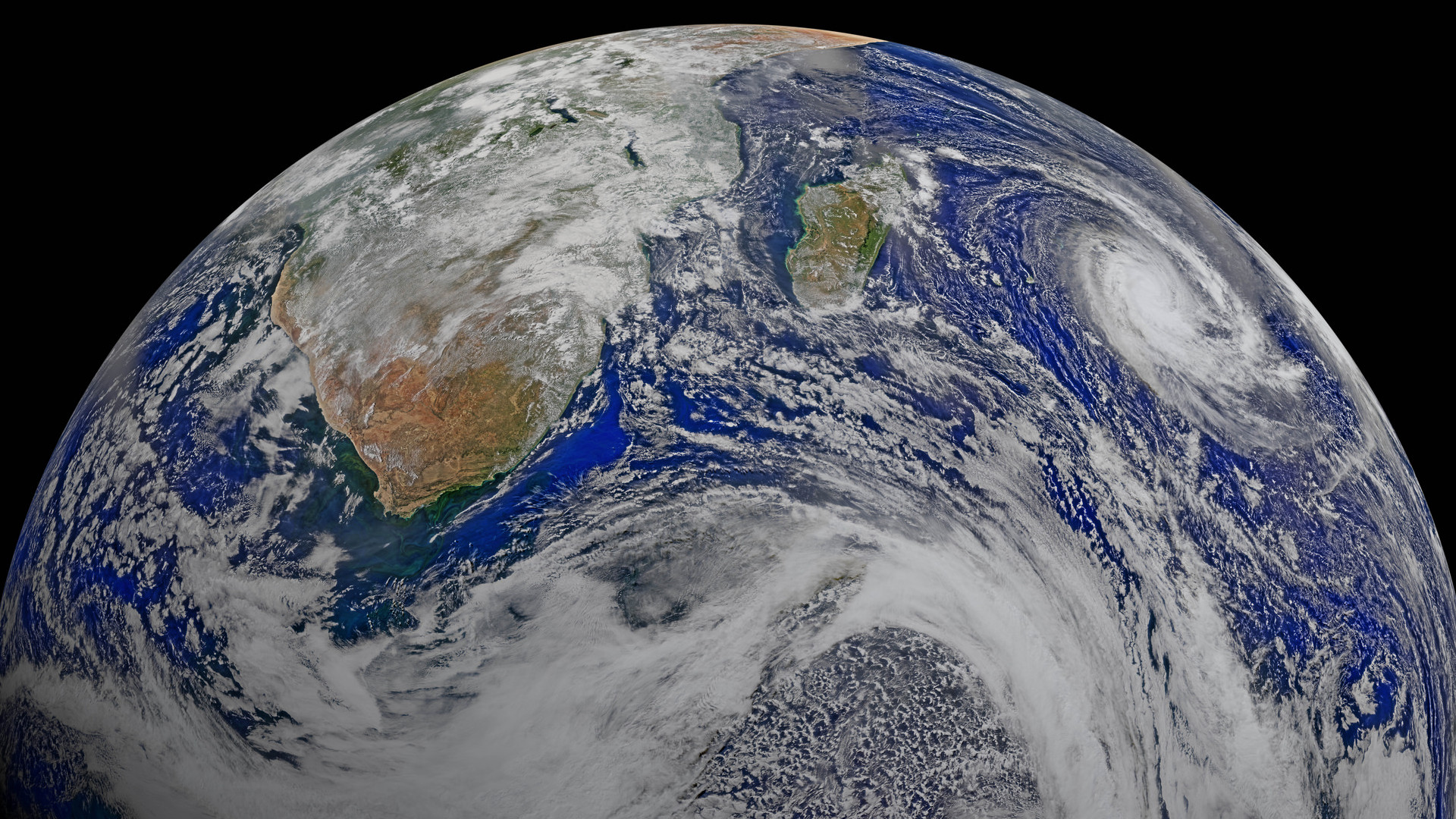

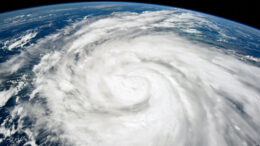

The ecological disaster that horrifies me the most is species extinction. Habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution and anthropogenic climate change are taking an unprecedented toll on us and the species we share this planet with. The extreme weather events we’ve been experiencing terrify me. As I write this, we’ve just seen Hurricane Ian ravage Florida’s Gulf Coast, Georgia and the Carolinas, leaving millions of people without power and causing billions in property damage.

The extreme weather events we’ve been experiencing terrify me. As I write this, we’ve just seen Hurricane Ian ravage Florida’s Gulf Coast, Georgia and the Carolinas, leaving millions of people without power and causing billions in property damage. What scares me is my own despair — the feeling, sometimes bordering on certainty, that we can’t come back from what we’ve done to the planet, and that my grandchildren and their children will be consigned to a hellscape of fires, floods, droughts and killing heat. I’m so angry at our own stupidity and shortsightedness. We’ve not only murdered ourselves but countless other species, and we’ve poisoned the sea with microplastics that will persist long after we’re gone.

What scares me is my own despair — the feeling, sometimes bordering on certainty, that we can’t come back from what we’ve done to the planet, and that my grandchildren and their children will be consigned to a hellscape of fires, floods, droughts and killing heat. I’m so angry at our own stupidity and shortsightedness. We’ve not only murdered ourselves but countless other species, and we’ve poisoned the sea with microplastics that will persist long after we’re gone. I’ve always pictured the end of the world as one hot-ass Earth, boiling whatever inhabitants are left, the surface uninhabitable, forcing the remaining humans underground.

I’ve always pictured the end of the world as one hot-ass Earth, boiling whatever inhabitants are left, the surface uninhabitable, forcing the remaining humans underground. It’s the suffering of the innocent that gets to me. Most of us are not innocent. I can’t claim to be, nor can any of us who knowingly participate in actions and behaviors that directly contribute to the progression of global warming.

It’s the suffering of the innocent that gets to me. Most of us are not innocent. I can’t claim to be, nor can any of us who knowingly participate in actions and behaviors that directly contribute to the progression of global warming. Something in me broke the first time I heard the Amazon was burning. I spent days watching the footage, horrified. I couldn’t believe it. I’d always taken a strange comfort in thinking that no matter what humans did, the rainforest would close itself over our cities — at least in Malaysia, where I grew up — and bury all remnants of us in the green. To child-me, there wasn’t anything greater than the rainforest, nothing more powerful than the natural world. And if the rainforests of Malaysia were potent, the Amazon felt almost deific to me.

Something in me broke the first time I heard the Amazon was burning. I spent days watching the footage, horrified. I couldn’t believe it. I’d always taken a strange comfort in thinking that no matter what humans did, the rainforest would close itself over our cities — at least in Malaysia, where I grew up — and bury all remnants of us in the green. To child-me, there wasn’t anything greater than the rainforest, nothing more powerful than the natural world. And if the rainforests of Malaysia were potent, the Amazon felt almost deific to me. It’s impossible to live in the American West without seeing that our water cycle is badly damaged. Climate scientists say we’ve entered a megadrought, and that the region is the driest it’s been for more than 1,000 years. There is no doubt that these conditions have been caused by climate change and human mismanagement, and that the drought’s impacts will have vast repercussions across the region.

It’s impossible to live in the American West without seeing that our water cycle is badly damaged. Climate scientists say we’ve entered a megadrought, and that the region is the driest it’s been for more than 1,000 years. There is no doubt that these conditions have been caused by climate change and human mismanagement, and that the drought’s impacts will have vast repercussions across the region. What frightens me more than any of the horrific daily reminders is that so many people in government and business know all of this to be true and refuse to take any real steps to combat the terrifying future ahead. All over the world, governments and corporations pay lip service to combating global warming and instead tell us plastic straws are the problem. And this pretend-ignorance makes it easy for so many people around the globe to also deny or at least ignore the reality unfolding around us.

What frightens me more than any of the horrific daily reminders is that so many people in government and business know all of this to be true and refuse to take any real steps to combat the terrifying future ahead. All over the world, governments and corporations pay lip service to combating global warming and instead tell us plastic straws are the problem. And this pretend-ignorance makes it easy for so many people around the globe to also deny or at least ignore the reality unfolding around us. The horrors are manifold, and the horrors are already here.

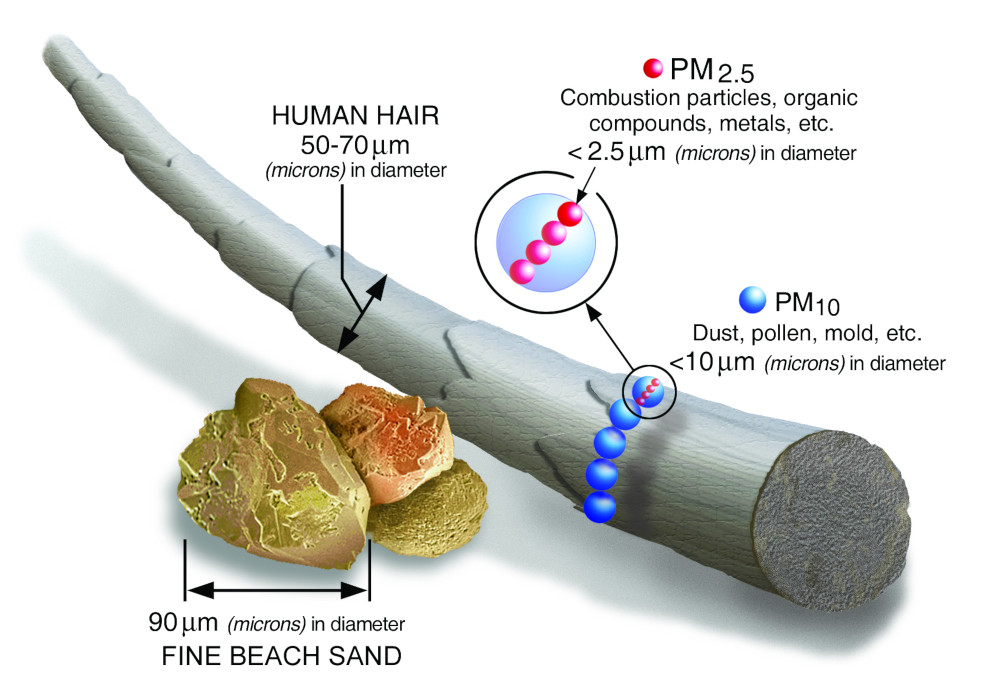

The horrors are manifold, and the horrors are already here. Melting permafrost is a part of that climate change that has its own terrifying aspects, like the release of greenhouse gases, damage to ecosystems and their biodiversity, and landslides and geological accidents. But it’s all the horror we cannot see that haunts me the most: the release of parasites, viruses and bacteria, microbes over 400,000 years old lying dormant in permafrost.

Melting permafrost is a part of that climate change that has its own terrifying aspects, like the release of greenhouse gases, damage to ecosystems and their biodiversity, and landslides and geological accidents. But it’s all the horror we cannot see that haunts me the most: the release of parasites, viruses and bacteria, microbes over 400,000 years old lying dormant in permafrost. I’m a country boy. I was raised to live off the land. I live in a rural area, sandwiched between a river and a forest. It’s never not quiet here. Be it daylight or long after dark, I can always hear frogs, insects, owls, ducks, geese, squirrels, and occasionally the soft drum of deer hooves or the padded footfalls of foxes and other animals.

I’m a country boy. I was raised to live off the land. I live in a rural area, sandwiched between a river and a forest. It’s never not quiet here. Be it daylight or long after dark, I can always hear frogs, insects, owls, ducks, geese, squirrels, and occasionally the soft drum of deer hooves or the padded footfalls of foxes and other animals. My horror is often inspired by outrage and frustration at the bad things that humans do to one another and the world around them to feed their wounds and demons. The denial of the truth that we are all connected is disheartening. It’s this denial that is degrading Earth’s climate, causing more wildfires, drought and stronger tropical storms.

My horror is often inspired by outrage and frustration at the bad things that humans do to one another and the world around them to feed their wounds and demons. The denial of the truth that we are all connected is disheartening. It’s this denial that is degrading Earth’s climate, causing more wildfires, drought and stronger tropical storms.