We’ve all seen photos of clear-cut forests with swathes of razed trees or deep scars in the ground from an open-pit mine. The damage to the species that live in these habitats isn’t hard to imagine.

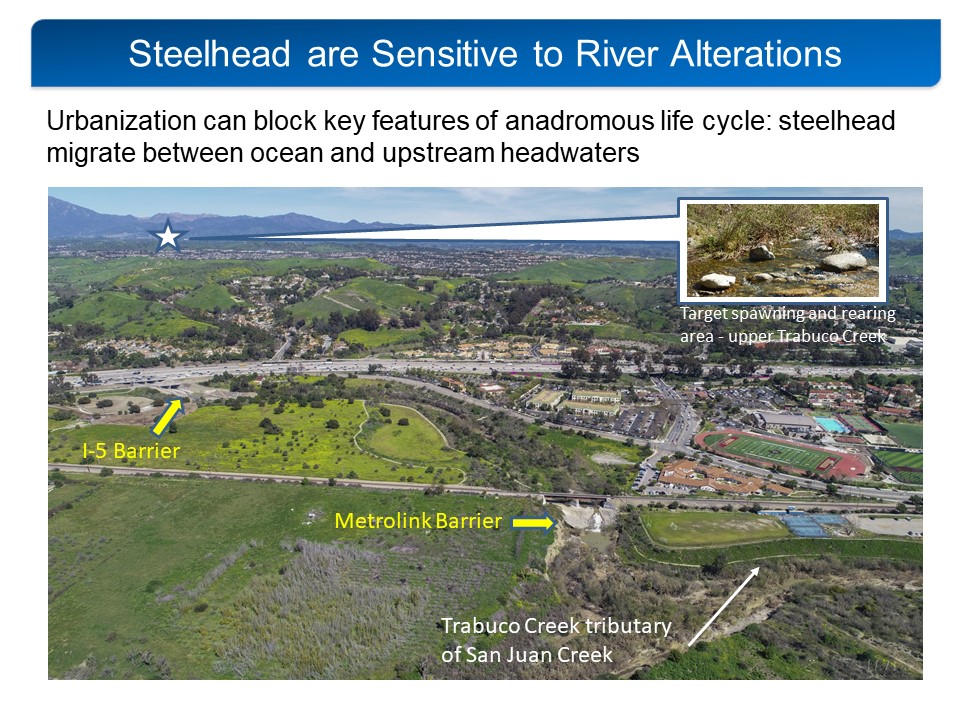

But the damage we’ve done to freshwater ecosystems isn’t so visible. In rivers or lakes, trouble often lurks out of view beneath the surface of the water — as with dams that block migratory fish or choke off needed nutrients and sediment.

Some experts believe we’re losing freshwater species faster than any others for one main reason: out of sight, out of mind.

A new study by more than two dozen expert scientists and policymakers aims to change that.

Their paper, “Bending the Curve of Global Freshwater Biodiversity Loss: An Emergency Recovery Plan,” published last month in BioScience, explains the growing threats to freshwater biodiversity and proposes a plan to tackle it by adjusting targets and indicators in two existing global frameworks — the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Time is of the essence, they write. Both frameworks are up for discussion and review by the world’s governments later this year, offering a unique but brief opportunity to make a difference for freshwater species.

Many of those species don’t have much time to wait. Freshwater species face grave threats, with 62% of turtles, a third of amphibians and more than a quarter of fishes currently threatened with extinction. Populations of freshwater vertebrates are falling twice as fast as vertebrates on land or in the ocean, and the population decline for freshwater megafauna — those animals that can reach 66 pounds or more — fell an astonishing 88% from 1970 to 2012. The Chinese paddlefish, one of the world’s largest freshwater fish, is now believed to be extinct.

“This decline and the possible solutions have not been that well publicized and aren’t strongly understood by decision makers,” says Jeff Opperman, the lead scientist for global freshwater issues at WWF and a co-author of the report.

Scientists do know what’s driving this decline: changes to river flow, pollution, habitat loss, overexploitation of species and invasive species. Yet no comprehensive global framework exists to tackle the problem with the urgency and at the scale we need, the report says.

That’s where the new study comes in. Opperman says it provides clear examples of how to add or amend language and goals to help protect and restore freshwater ecosystems into both existing international frameworks.

“At least we can get these global frameworks and targets to specifically recognize the challenge and highlight opportunities that we have in terms of fresh water,” he says. “That can help raise expectations for how the world is going to handle this.”

The plan lays out six priority actions for global action:

- Accelerate the implementation of water protections against agricultural, industrial and domestic use to ensure that rivers have enough water to protect freshwater habitat.

- Improve water quality. Pollutants vary by region, but across Latin America, Africa and Asia, 80% of sewage discharged into waters hasn’t been treated adequately.

- Protect and restore critical habitat, like inland wetlands, which have decreased by 87% since 1700.

- Prevent the exploitation of freshwater species and river structures. Better policy frameworks could prevent overharvesting of fish, crabs, frogs and other species, as well as mining sand and gravel that can destroy freshwater habitat.

- Prevent and control the invasion of non-native species.

- Protect and restore the connectivity of freshwater systems. Dams, for example, bisect riverine habitat and alter flows. And flood management structures like levees separate rivers from floodplains.

The paper translates these priority actions into specific recommendations. For instance, the researchers recommend that the Convention on Biological Diversity amend its ecosystem services goals to emphasize the many values of healthy freshwater ecosystems, not just the need to protect water supplies.

The authors also propose adding language to include inland freshwater fisheries in fisheries management targets, instead of just marine fisheries. An estimated 158 million people are fed by freshwater fisheries, but they’re often overlooked by governments because they’re outside traditional markets.

In the Sustainable Development Goals, the researchers advocate including an emphasis on nature-based solutions in the sustainable infrastructure goal. And they recommend a new indicator to track the number of water bodies that have implemented environmental flows.

For each recommendation in the study, the researchers also provide real-world cases that show the solutions in action and best practices that could help other countries implement similar strategies.

“These aren’t academic recommendations,” says Opperman. “We’re showing which countries have done this and the benefits.”

The report was just released in February, but Opperman says it’s already generated some good high-level discussions. “The key agencies that are involved in the dialogue have been receptive to this emergency recovery plan as useful guidance,” he says.

But the truly hard work will be if, or when, governments put these guidelines into practice. Researchers will need to play a key role, too, in maintaining and increasing the amount and the types of things they track related to freshwater populations and ecosystem services.

“If we’re not able to monitor and document trends, it will be hard to know how we’re performing against targets or just performing in general,” Opperman says.

We’re a long way from what’s needed at the global level to stem the loss of freshwater biodiversity, but the study’s authors contend that right now we have “a once in a generation opportunity to promote such improvements at scale and to avoid the irreversible losses of species and habitats.”

Will global leaders rise to the challenge?

![]()

Those themes run strong through this month’s new environmental books, including an emotional memoir from climate activist Greta Thunberg and her family that’s sure to inspire discussions among other families around the world.

Those themes run strong through this month’s new environmental books, including an emotional memoir from climate activist Greta Thunberg and her family that’s sure to inspire discussions among other families around the world. Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis

Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis The Story of More: How We Got to Climate Change and Where to Go From Here

The Story of More: How We Got to Climate Change and Where to Go From Here Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils

Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils Earth Day and the Environmental Movement

Earth Day and the Environmental Movement The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court

The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court Irreplaceable: The Fight to Save Our Wild Places

Irreplaceable: The Fight to Save Our Wild Places American Zion: Cliven Bundy, God & Public Lands in the West

American Zion: Cliven Bundy, God & Public Lands in the West Greenovation: Urban Leadership on Climate Change

Greenovation: Urban Leadership on Climate Change Other notable books out this month include

Other notable books out this month include