More than 150 national forests and 20 national grasslands represent an astonishing range of ecosystems where much of our country’s biodiversity thrives. Collectively, they comprise the National Forest System, or NFS, for short.

For many Americans, however, the acronym NFS now means something very different: “Not For Sale.”

That was the mantra on a steamy late June afternoon as I marched with thousands of protesters along Santa Fe streets on our way to the Eldorado Hotel. There, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum and three other cabinet secretaries were to speak at the annual conference of the Western Governors’ Association.

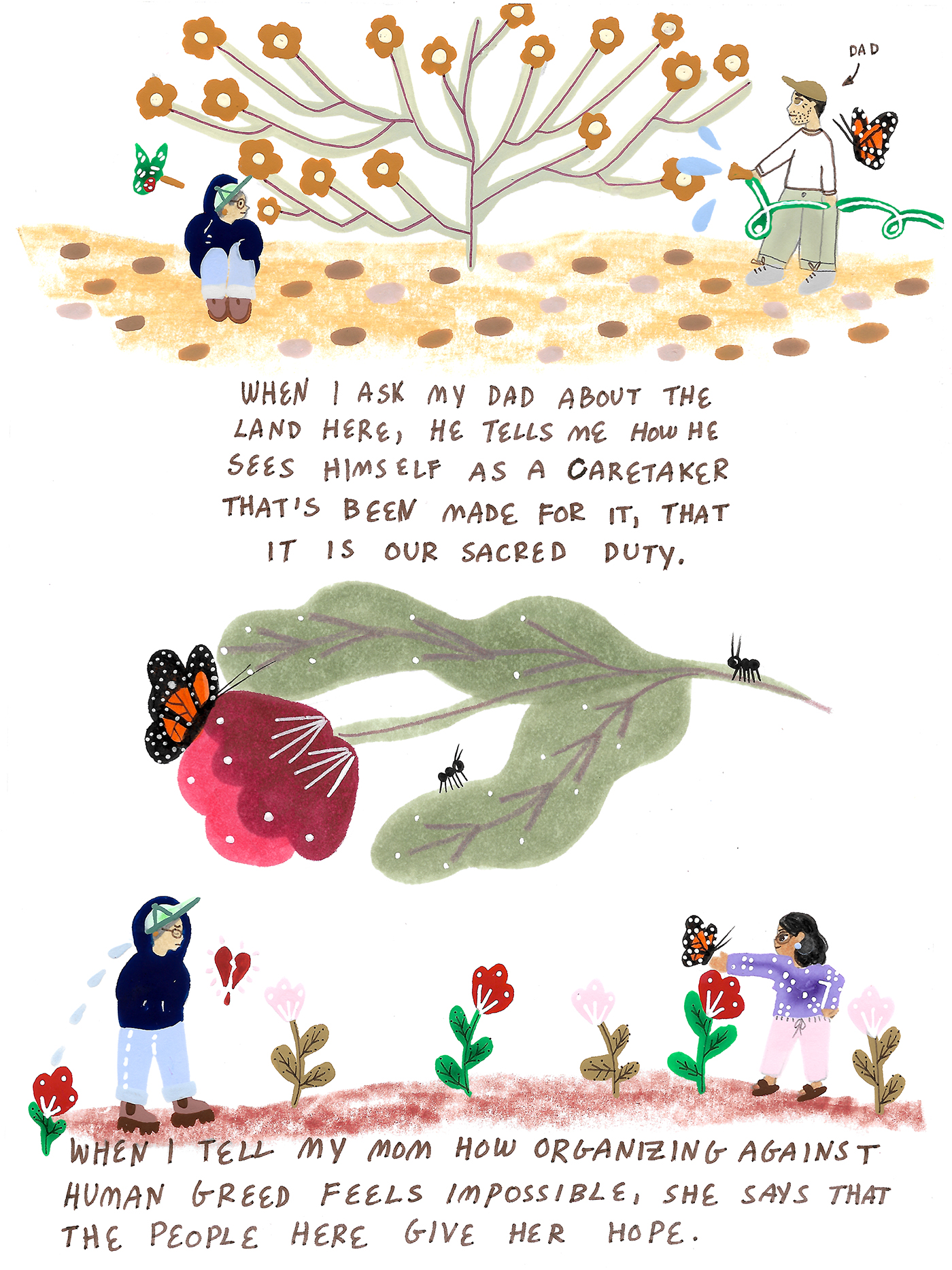

While marching, I was flanked by an array of lively signs. “Nature is Sacred and Not For Sale.” A hummingbird photo was bordered by the words “Nature Heals.”

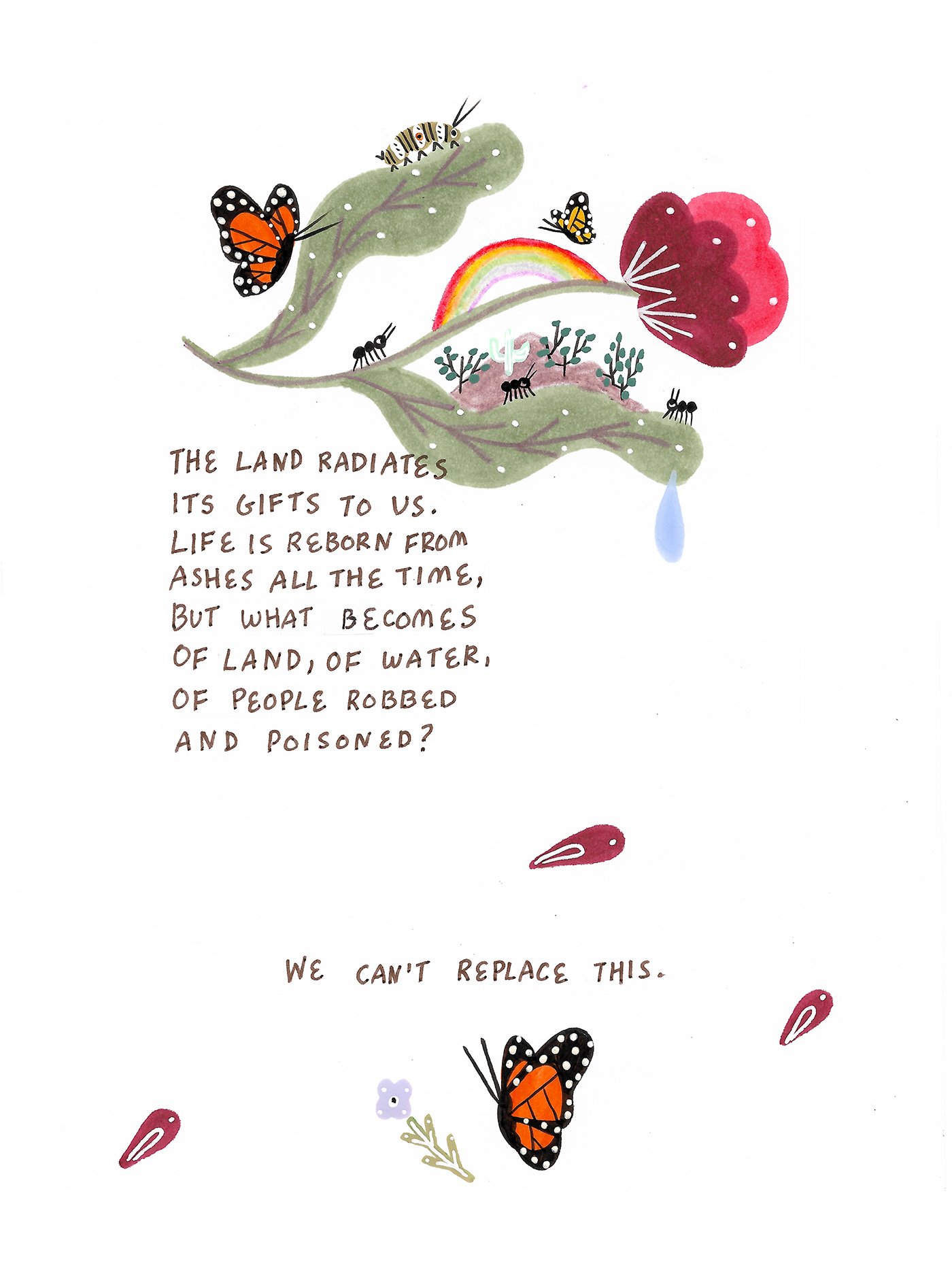

Once nature is fragmented beyond repair, however, it can no longer heal us. Habitat loss remains the primary driver of biodiversity loss. As I write in my new book, The Light Between Apple Trees, when species diversity and gene flows are impoverished, ecosystems can no longer remain resilient or support the “assembly of life” that depends on them. Aggressive fragmentation will follow the Trump administration’s and Utah Senator Mike Lee’s frenzied and persistent, if temporarily stalled, attempts to sell millions of acres of public land.

Standing before the steps of the Eldorado Hotel, the crowd chanted “Not For Sale.” Sage smoke wafted across my face. I stood behind tribal members of mixed Navajo and Chicana ancestry, including a woman holding a gorgeous infant. A dozen steps above us, armed state police formed a line to block the entrance to the hotel. They were roundly booed by the protesters.

If Secretary Burgum wasn’t going to make an appearance, the crowd wanted their governor, Michelle Lujan Grisham, to speak to their concerns. “We want the governor!” they shouted. But a protest organizer intervened and requested a Navajo man to offer a prayer.

An Indigenous grandmother mounted the steps and introduced a young Navajo man who had been drumming behind me. He went up and offered a lyrical prayer, asking that Mother Earth be protected and wild animals feel safe. The prayer had a unifying effect on the crowd. The Navajo infant had grown irritated by the hot sun, but she soon fell asleep to chants of “Not For Sale — Ever! Never!”

Signs bounced up and down as we marched around the hotel to a tinted glass wall behind which the Interior Secretary, cabinet ministers, and governors were believed to be standing. The signs read: “We Are All In This Together” and “Then They Came for Our Trees.” Children I’ve known since they were babies wielded signs such as “Keep Your Hands Off Our Camping Lands” and “I Love Nature.” And, “NFS: Not For Sale.” Conservationist William deBuys waved a blue-green Earth flag. Our rhythmic clapping mingled with chanting “Not For Sale.”

As I marched on, a sign proclaiming “America’s Best Idea Is Worth Fighting For” refreshed me. The public lands in danger of being lost forever are the responsibility of the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management. Portions of the Carson National Forest where I researched sensitive bird species such as the Northern goshawk are at risk, as are pieces of BLM land such as a historic orchard that inspired my new book.

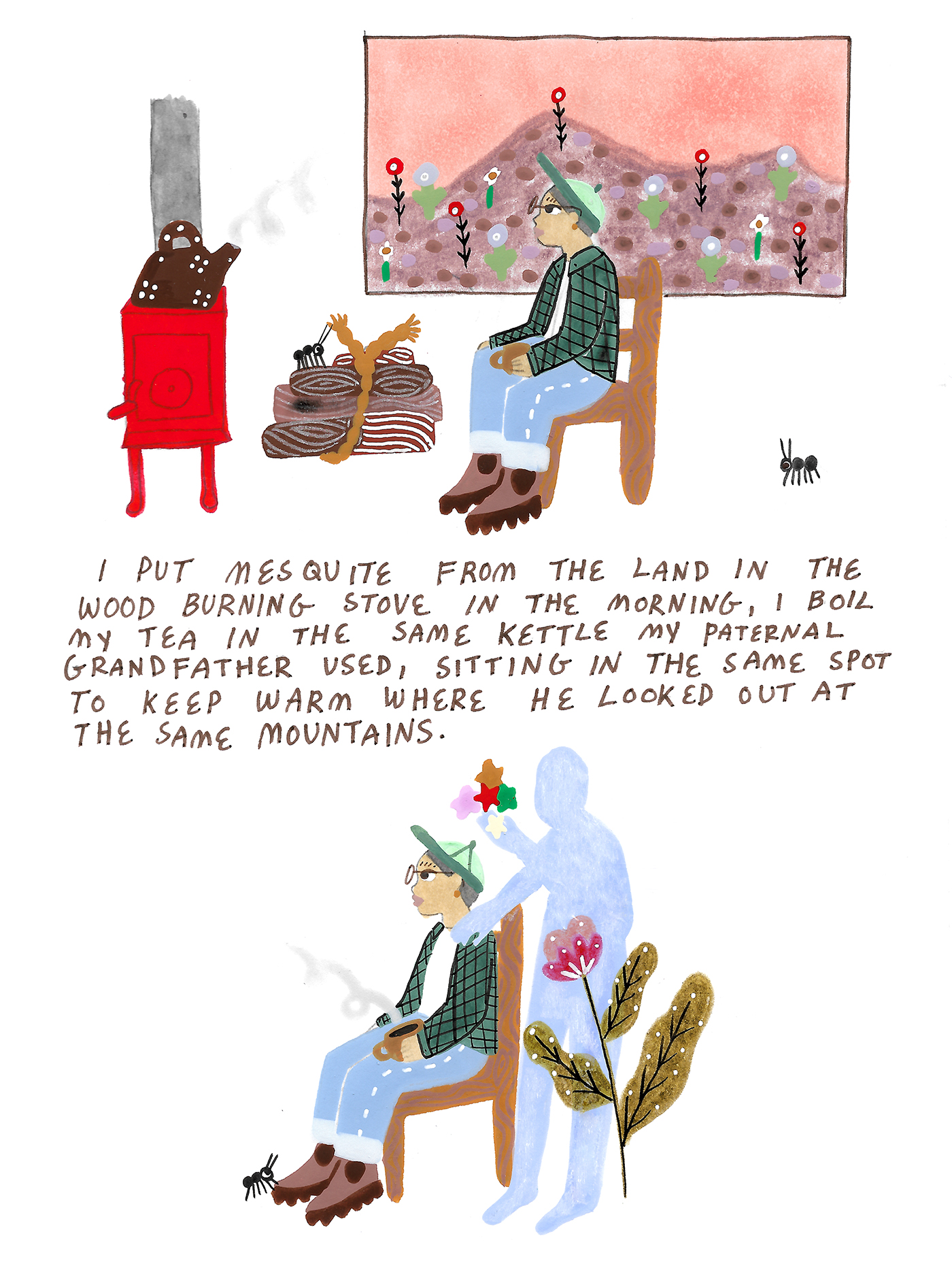

Over a decade back, the BLM purchased one of the oldest orchards in the area where I live. The property has been likened to New Mexico’s Walden and is a haven of biodiversity — with 120-year-old apple trees, a constellation of birds, and an acequia that has been flowing since 1718. Ancient orchards are repositories of cultural and ecological history and should not be up for sale to the highest commercial bidders. Among the apple varieties that grow in this orchard is the Wolf River apple, a large baking apple that was initially established in 1856 along Wisconsin’s Wolf River by a woodsman from Québec.

While the apple is a beloved American fruit, many people don’t know about our country’s storied apple history because they lack access to historic orchards and wild areas where feral apples still grow. Auctioning off public lands near Western cities, as Lee and others proposed, will only worsen the disconnect between us and nature.

The day after the rally brought a temporary reprieve. The provision to sell off public lands had been introduced in the Senate without being voted on in the House, and Senate parliamentarian Elizabeth MacDonough determined that its language violated the rules of the reconciliation process. The Byrd rule prevents the insertion of “extraneous provisions” that don’t directly impact spending and revenue.

In response to public backlash, Lee signaled that national forest land would be excluded from the sale but brought back the provision in a revised form. Amid fresh backlash, this time from conservative hunting and fishing groups as well, Lee’s revised proposal ran into another setback. Unable to guarantee that the land wouldn’t get sold off to investment companies and foreign interests, the provision was pulled at the last minute from the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.”

While the rally and across-the-aisle backlash have earned public lands a brief reprieve, the impetus to sell them remains strong, and the future of the BLM orchard I love is far from secure. Federal agencies that manage public lands have suffered deep budget cuts. As I have discovered on research trips to public lands, it takes dedicated rangers to keep a historic orchard watered.

This spring and summer, as I researched grassland birds in national wildlife refuges, I found visitor centers shut, vault restrooms locked, and supervisors and managers “retired.” All of these felt like signs to discourage people from visiting public lands, which would further erode our connection to nature and perhaps weaken our outcry the next time public lands are threatened. At a time when our forests and grasslands remain vulnerable to a future selloff, Americans could seize the reprieve we have earned to make big, beautiful signs about the ways in which nature sustains our bodies and spirits. Such essential sustenance should never be up for sale.