Later this month world leaders will gather in Hiroshima, Japan for the 49th G7 summit, the annual meeting devoted to issues of global diplomacy. Will they listen to the voices of their youngest constituents and act on climate change?

A few weeks ago the Y7 — the G7’s official youth engagement group — concluded work on our Youth Communiqué. Developed by youth representatives from each country in the group, it proposes policies to heads of state on pressing global issues like climate and environment, peace and security, global health, economic resilience, and digital innovation.

This year’s Y7 Climate and Environment discussions, in which I represent European Union youth, call on the G7 to ensure a just and orderly transition, restore biodiversity and protect ecosystems, and prioritize and finance resilient human settlements. After months of youth consultations, those recommendations have now been handed over to the Japanese G7 presidency, Prime Minister Fumia Kishida.

While leaders read our recommendations as part of their stated aim to take an intergenerational approach, one question continues to spiral in my head: What if our governments decided to act on climate change and environmental degradation as if this will affect our generation?

We’re left with seven years to act for life within planetary boundaries, as shown by the latest IPCC report. Considering the rapidly closing window of opportunity to limit the global average temperature rise to below 1.5°C, the viability of humanity rests on the actions we take today.

High-income and high-pollution countries need to lead the transition, granting our generation the basic human need to walk on healthy soils and breathe clean air. Our G7 Youth Communiqué asks for nothing more than this.

In truth 1.5°C should not be considered a target but a ceiling. Overshooting this means entering a blind spot: overstepping planetary limits in which life has flourished for millions of years.

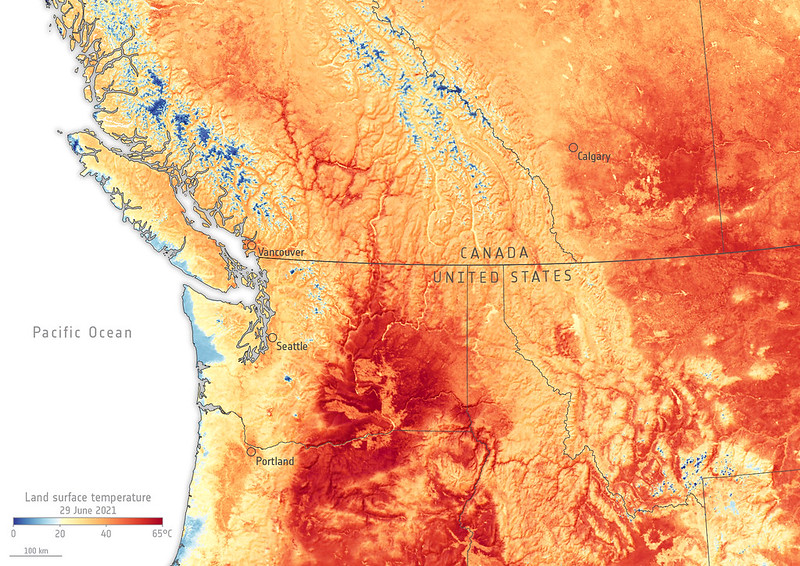

The difference between 1.5°C and 2°C is not just a temperature rise of 0.5°C. It means that climate risks will be at least twice as disruptive. Considering nearly half of the world’s population lives in the danger zone of climate impacts, every fraction of a degree counts.

We already see the disproportionate effect of 1.1°C warming above preindustrial levels, particularly on the lives of vulnerable communities — those that have contributed the least emissions and pollution.

At the same time, public and private financing of fossil fuels is still greater than for climate adaptation and mitigation.

As governments continue to shake hands with the fossil fuel industry, current climate policies are projected to increase global warming by 3.2°C in 2100.

The Y7 Communiqué will not be the last message from my generation demanding change. Another scientific report, youth engagement group and United Nations initiative will follow — all repeating the same message.

Yet what we need is the political will to comply with Earth’s nine planetary boundaries.

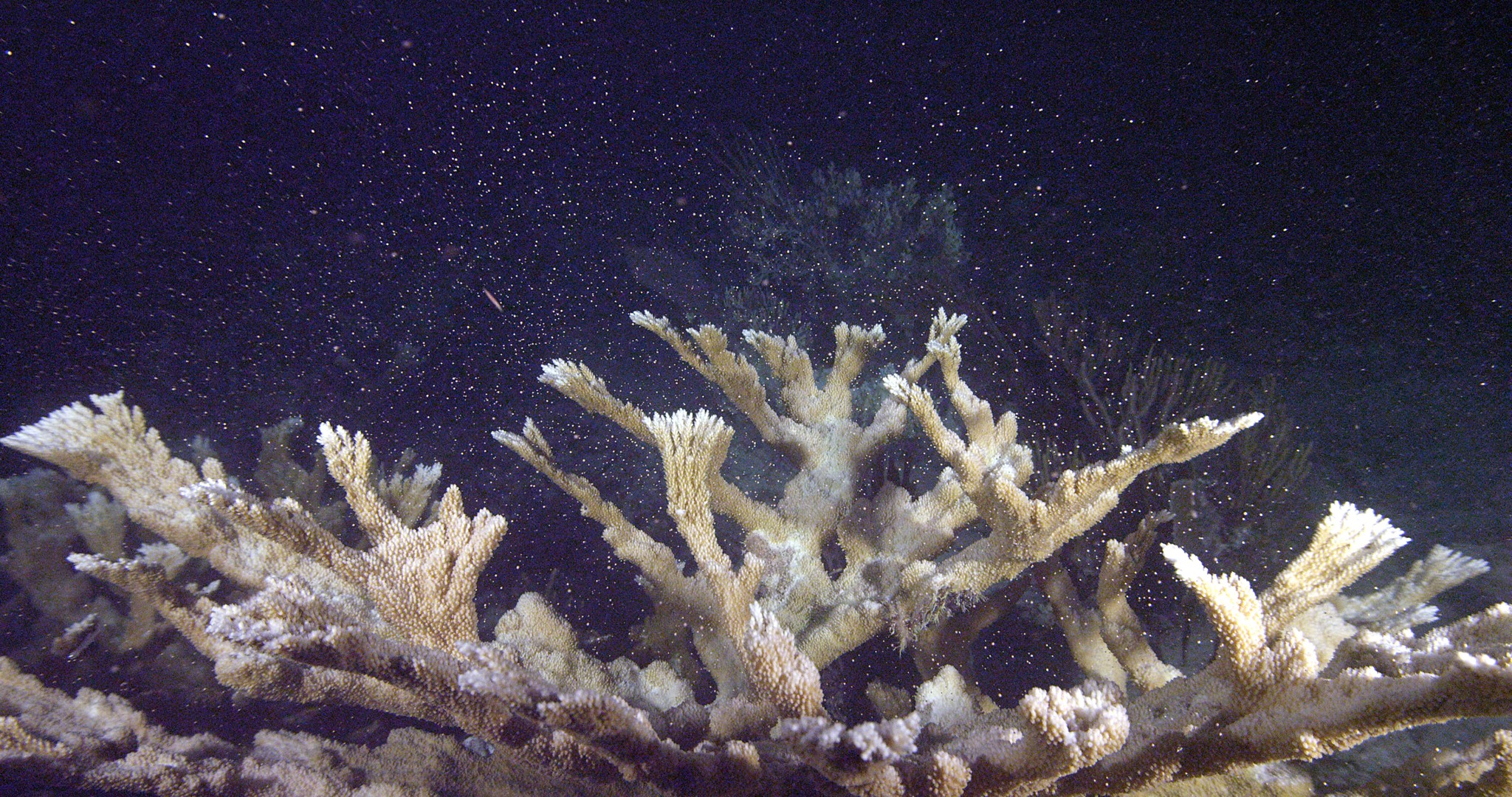

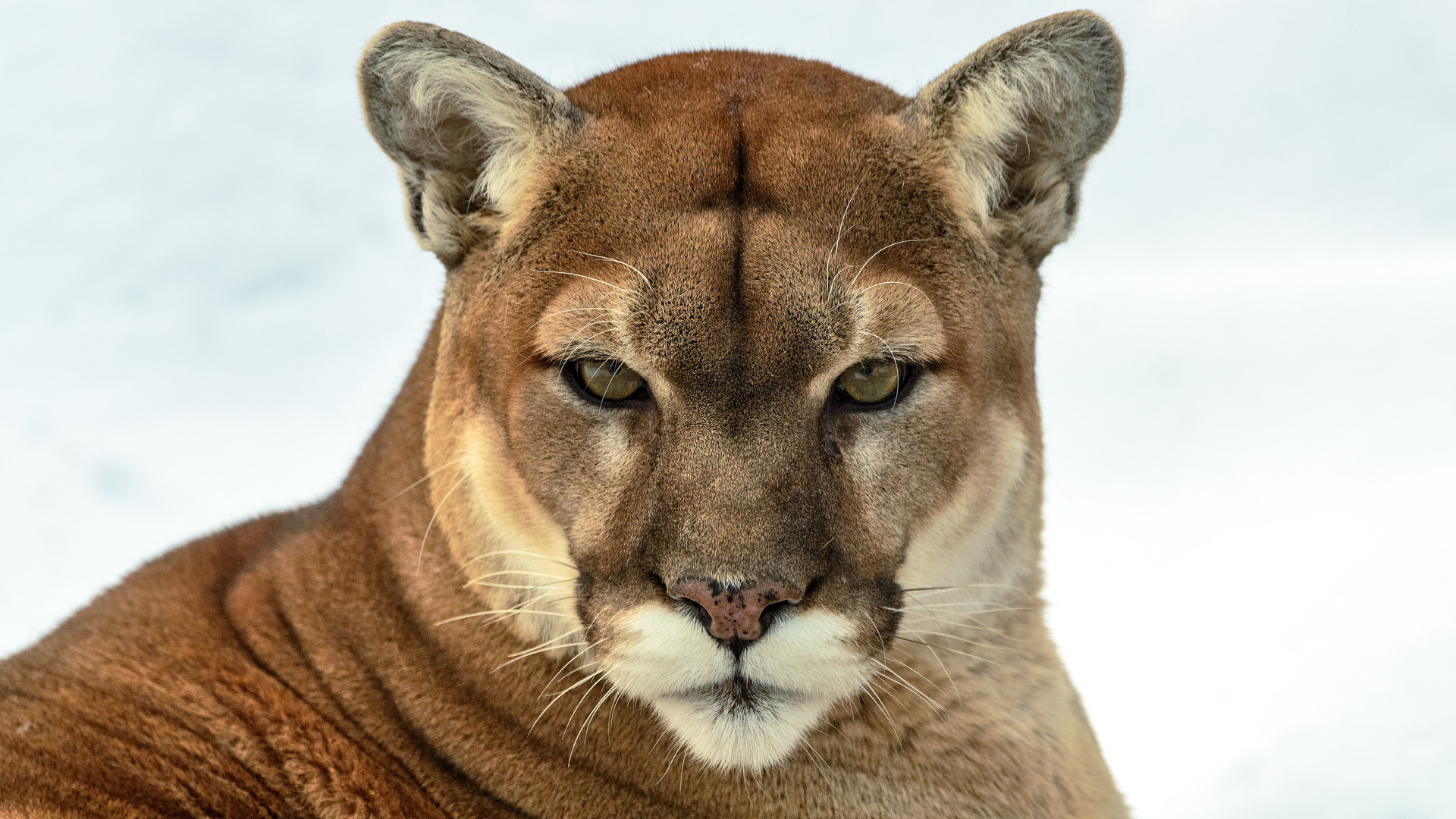

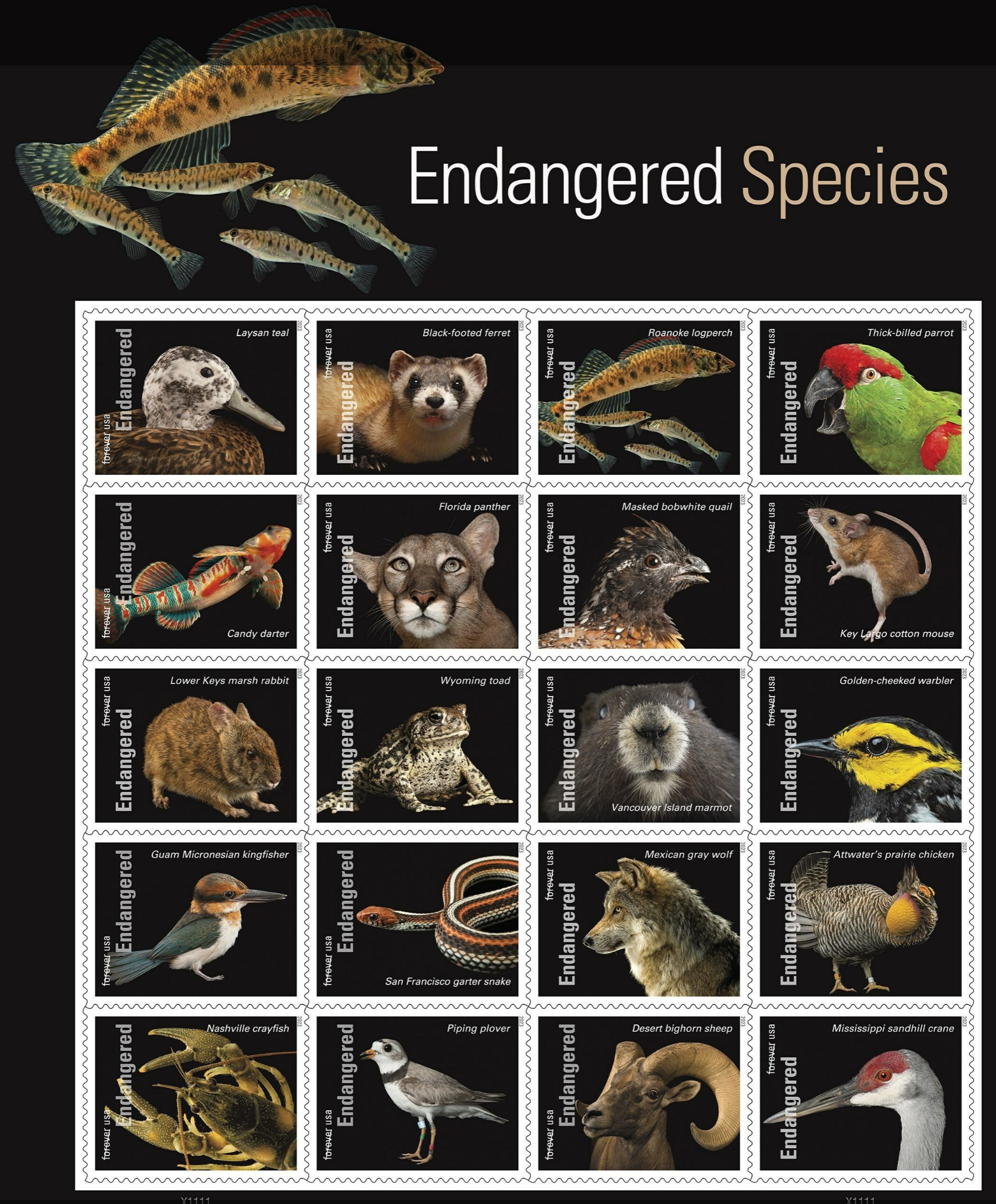

These boundaries — climate change, ocean acidification, stratospheric ozone depletion, biogeochemical flows of the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, freshwater use, change in land use, erosion of biodiversity, atmospheric aerosol loading, and novel entities — are required for us to live in harmony with nature. By now, 6 out of 9 have been crossed due to human activity, particularly in high-income countries.

So unless we substantially change our socioeconomic structures — how we work, move, produce and communicate — the stability of global ecosystems is put at stake.

True action asks us to give up current economic models requiring unrelenting growth to produce and consume products and services which conflict with the planet’s natural metabolism.

True action asks us to rethink our relationship with nature as an integrated part of life whilst moving towards absolute resource use reduction.

True action allows our and future generations the basic human need for breathable air, clean water, and sustainable food systems.

With these goals in mind, our Y7 Communiqué calls on the G7 to:

-

- Phase out and commit to no new investment in the exploration or production of fossil fuels by endorsing the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, redirecting investments into renewable energy projects and prioritising energy demand reduction.

- Strengthen loan-free climate financing mechanisms — and embed the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, intergenerational dialogues, and decolonial frameworks in all climate policies.

- Deliver socially equitable commitments to reverse biodiversity loss, deforestation, and soil degradation by acting on the Global Biodiversity Framework’s 30×30 target and endorsing responsible nature-based solutions.

- Lead the transition to regenerative agriculture and plant-based food systems by divesting from intensive monocultures, acting on the Global Methane Pledge and establishing ambitious animal welfare standards for livestock.

- Support the United Nations Convention for the Laws of the Seas by enforcing international surveillance systems against illegal, unregulated and unreported fisheries, ending dangerous indiscriminate fishing techniques, and banning deep sea mining.

In the next seven years, high-income countries like the G7 can and must decide to act on climate change and environmental degradation — taking an active stance for climate justice by limiting unfolding damage.

Our generation depends on it.

Get more from The Revelator. Subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.