As the climate crisis escalates, a huge amount of attention and money is being focused on climate solutions. These can be divided into two categories: solutions that pursue “mitigation,” which lowers greenhouse gas emissions, and those that pursue methods to adapt to climate impacts to increase human and ecological resiliency.

Dams, of course, create enormous environmental harms, many of which have already been described in scientific literature. Equally well documented is the fact that removing dams can restore seriously damaged ecosystems. But missing from almost every climate-solution story and study is how dam removal can be key for both mitigation and adaptation.

Here are 10 reasons why dam removal fights climate change:

1. Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Dam removal reduces greenhouse gas emissions, especially methane. An increasing amount of scientific evidence, including from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, indicates that dam/reservoir systems can be a significant methane emitter. In some cases, hydropower dam projects can emit as much total greenhouse gases as a coal-fired powerplant.

2. Natural Flows

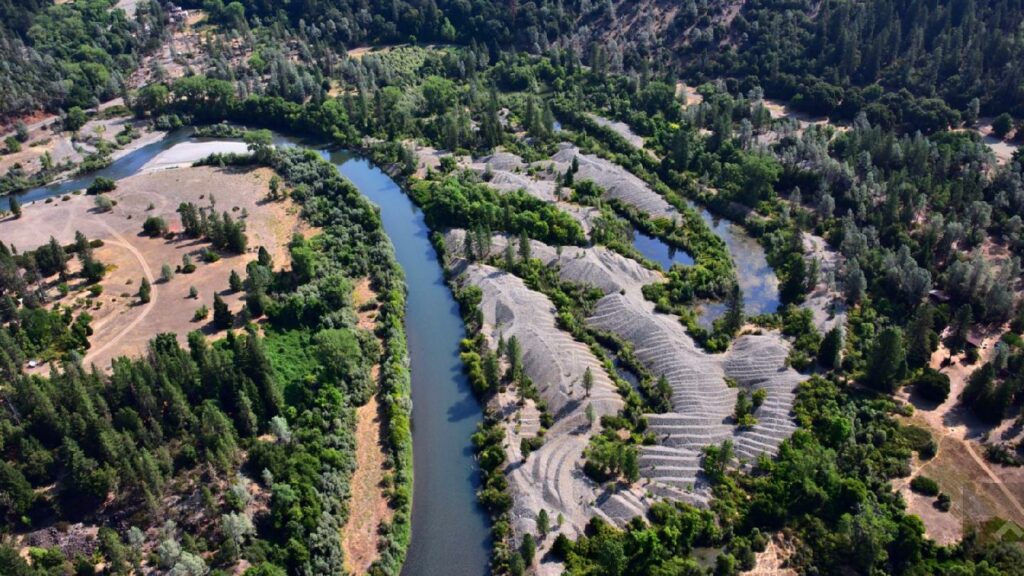

Dam removal allows rivers to meander through their historic valleys, plains and forests. In so doing, rivers transport surrounding organic material, such as decomposed plants and soil, to sea. Once there, much of the material sinks to the bottom of the ocean, where it’s transformed and locked into rock formations. These river plumes, which can extend for miles into the ocean, are carbon sinks.

3. Carbon Sinks

Dam removal allows landscapes that have been flooded to regrow their native vegetation: also carbon sinks. In the United States alone, the largest 150 reservoirs submerge over seven million acres of land. In the Canadian province of Quebec, over 6 million acres of previously forested land is covered by reservoirs. Globally, there are likely over 100 million acres of land flooded by reservoirs.

4. Biodiversity

One of most detrimental ecological impacts of climate change is the diminishment of biodiversity. The construction of dams and reservoirs exacerbate this loss of biodiversity by flooding riverine ecosystems that are biodiversity hotspots. Dam removal restores native biodiversity, a key climate adaptation strategy.

5. Forests

Healthy forests — especially old-growth forests — are key carbon sinks in many ecosystems of the world including the Pacific Northwest. Dam removal that restores the migration of anadromous fish, such as wild salmon, are key fertilizers for healthy forests as the fish swim upstream and die, replenishing the soil and ecosystem.

6. Sediment Transport

Climate change is causing rising sea levels that batter coasts and deplete beaches in California and across the planet. Dams block natural sediment from flowing to the sea; dam removal will allow sediment to reach estuaries and coasts where it can help provide the material to rebuild beaches. Sediment in river deltas can also help protect against salt-water encroachment, worsened by rising seas, in places like the Mississippi River Delta.

7. Fish Populations

In parts of the United States and elsewhere, dams have decimated fish populations that are a principle food source for local and Native peoples. Dam removal allows fish to naturally spawn, reproduce, and migrate along vast stretches of rivers. As climate change intensifies, freshwater river fish are increasingly important as a human food source.

8. Water Supply

Reservoirs, large and small, allow vast amounts of water to evaporate off their surfaces, and this problem gets worse as temperatures rise. As just one example, in the drought- and overuse-plagued Colorado River in the southwest, it’s estimated that 10% of the entire flow of the river evaporates every year. Removing dams and storing water in underground aquifers makes water supplies more resilient in a warming world.

9. Climate Resilience

Climate change is intensifying extreme weather including rainfall, floods and melting glaciers. Most dams, large and small, were constructed to withstand a range of weather events that may no longer be the norm. Further, dams need an increasing amount of maintenance and repairs to withstand extreme floods. Recent massive floods in Libya and India that have caused large-scale dam collapses suggest that dam removal can increase the health and safety of downstream human settlements in the path of climate change.

10. Cooling Effect

As climate change causes the planet to warm, heat waves — especially in urban areas — cause heat stress and deaths. Not only do healthy flowing rivers provide a cooling effect to surrounding urban heat islands, but people increasingly use local rivers to stay cool on hot days. Dam removal ensures that rivers flow and stay cooler, cleaner, and healthier in a climate-changed world.

With more than 91,000 dams in the United States, it’s important to evaluate them all for removal as potential climate solutions. In many cases both mitigation and adaptation can be achieved in one single dam removal event. Few other climate solution projects of this breadth and magnitude exist.

While most other climate solutions involve building some type of structure or facility as a technical solution, dam removal involves tearing a structure down and letting natural ecological processes be restored. Such “nature-based solutions” that decrease the number of dams blocking rivers must be considered in the vast mix responses to the escalating climate crisis.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

Previously in The Revelator:

Dam Accounting: Taking Stock of Methane Emissions From Reservoirs

![]()

As a child, I watched the men I loved in my family lift their high-powered rifles and shoot one prairie dog after another and another for fun, and then walk away. They called them “pop-guts.” On the way back to our camp, I stepped over their small blood-soaked, blown-apart bodies left in the matted grasses of their prairie dog town. And then, a single prairie dog raised her head out of a burrow and stood up and faced me. I froze in place, unable to avoid her gaze. She disappeared underground.

As a child, I watched the men I loved in my family lift their high-powered rifles and shoot one prairie dog after another and another for fun, and then walk away. They called them “pop-guts.” On the way back to our camp, I stepped over their small blood-soaked, blown-apart bodies left in the matted grasses of their prairie dog town. And then, a single prairie dog raised her head out of a burrow and stood up and faced me. I froze in place, unable to avoid her gaze. She disappeared underground.