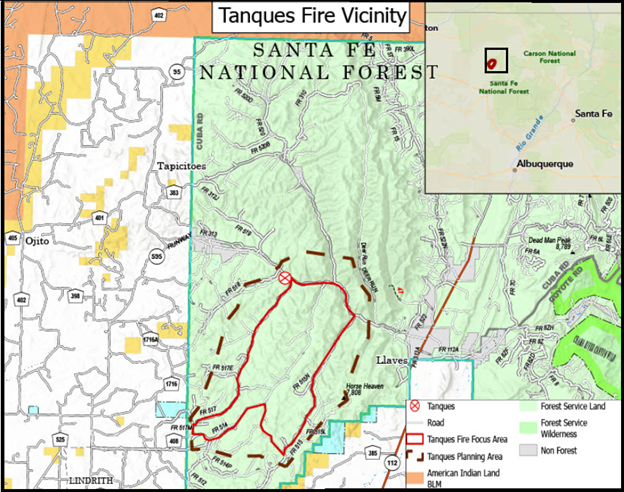

Wildfires tore through central and northern Portugal this September, burning more than 350 square miles in a matter of days. Nine people were killed. As many as 11,300 were affected, according to the European Union’s Copernicus system.

While these are some of the worst blazes in recent years, wildfires sweep through Portugal every summer, burning an average of just over 1% of the country annually — more than double that of the second-most affected EU country, Greece.

As the climate changes, these fires are only getting worse, says doctoral researcher Tiago Ermitão from the Portuguese Institute for Sea and Atmosphere, who studies how vegetation recovers after fires. He adds that hot and dry conditions, “mainly caused by anthropogenic activities,” have significantly increased fire susceptibility and risk in Portugal in recent years.

But what makes this small country on the edge of the Atlantic so vulnerable?

One factor has its roots in the authoritarian regime that ruled the country for more than four decades.

In the 1920s and 1930s, a military dictatorship and the corporatist Estado Novo (New State) that followed implemented sweeping agricultural reforms across Portugal, focused on ideas of self-sufficiency and ruralism that were popular among Europe’s authoritarian regimes at the time.

Wheat vs. Heath

The first of these policies was the Wheat Campaign (a Campanha do Trigo), which aimed to make Portugal’s food supplies self-sufficient through increased cereal production, predominantly in the central Alentejo region.

The policy had some success, with wheat production booming in just a few years. However, this was mainly due to expansion into heathlands rather than the intensification of existing farms many agronomists had envisioned. The nearly 30% increase in Alentejo wheatfield acreage between 1927 and 1933 was spearheaded by sharecroppers, driven by the high prices of a protected market, subsidies for newly cultivated land, and a lack of access to quality fields.

With the help of newly available fertilizers, they cultivated the poor soils where heathland grew.

But the wheat boom wouldn’t last for long. By the mid-1930s, overproduction removed many of the financial motives, and the intensive use of thin soils led to severe erosion and significantly decreased productivity by the 1940s and 1950s.

Only a couple of decades after the wheat campaign began, there was “an official realization that soil degradation had reached serious proportions,” agriculture started to decline, and people began abandoning these newly cultivated lands, according to the Desertification Indicator System for Mediterranean Europe project.

Foresting the Commons

Meanwhile, in the north of the country, another of Estado Novo’s agricultural campaigns was getting underway: the Afforestation Plan. In the mid-1930s, the Forestry Service identified some 1,600 square miles of mountainous common land called baldios, which the regime interpreted literally as “barren” or “waste” lands, to be forested over three decades.

This policy would convert common property to state forests, which could then, according to justifications at the time, supply new industries and energy generation.

By 1968 the Forestry Service had planted about 1,000 square miles, and industries such as furniture making and paper pulp had started operating, some of which still exist. The Navigator Company, for example, is a multibillion-dollar pulp and paper company originating in 1950s northern Portugal.

The baldios that were planted during this time were certainly degraded before Estado Novo took power, with only 7% of Portugal covered by forest at the turn of the century, according to Iryna Skulska, a researcher at the Centro de Ecologia Aplicada Prof. Baeta Neves (named after the late forestry professor) who has studied the environmental impacts of the regime.

“[The baldios] were very, very exploited — overly exploited — by local communities,” because the “Portuguese rural community in the 19th [and] 20th century were very, very poor,” she says.

However, rather than reviving mixed forests, the regime established pine monocultures. “They implemented the forest monoculture stands … which in terms of biodiversity, is not a good idea,” Skulska says. “They wanted to use… species that adapt very quickly to the poor condition of the soil, [and] at the same time produce [wood] very quickly.”

What’s more, these “wastelands” were only considered as such because they were uncultivated, not because they were unused.

“One hundred years ago, before the Second World War, you had a lot of pastoralists who used to drive their flocks of sheep, goats, cows, etc, through the landscape,” explains Pedro Prata, executive director of Rewilding Portugal. “This landscape was much more used in terms of the collection of vegetal matter. Everything was used, from creating the sleeping beds of the animals, to compost for manure, to fire, and as energy.”

These policies in the north were not only driven by the desire for self-sufficiency but also by the social structures of the region. A survey in the 1930s found that 14% of households were managed by single women, which the state chalked up to the “improper” sexual conduct of male and female shepherds, completely out of line with the authoritarian Estado Novo’s conservative ideals.

The Internal Colonization Board, which implemented parts of the agricultural plans, thus looked to draft in settlers from more densely populated areas and, as historian Tiago Saraiva puts it in a paper on the subject, “convert local people to the moralizing activity of agriculture.”

But while the landscapes were converted, the people were not, and the destruction of the common lands brought an end to many of the pastoral communities that relied on it. Once again, far from creating the rural idylls that authoritarian regimes of the time idolized, this policy led to a massive migration away from rural areas.

Fragmented Landscapes, Fragmented Communities

These two campaigns had immediate and profound effects on ecosystems and biodiversity. From the uprooting of heathland in the Alentejo to the pine monocultures in the north, the changes contributed to the destruction and fragmentation of native landscapes and the decimation of indigenous species such as wolves, Iberian lynx, and imperial eagles, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, a multicountry project that examined the impact of ecosystem change on human well-being in the early 2000s.

This environmental destruction echoes today, with many species still missing from the landscape.

View this post on Instagram

More concerningly, these policies also contributed to the depopulation of rural areas and the “consequent abandonment of agricultural activity” that continues to this day, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Along with monocultures of “high fire risk” species like pine and eucalyptus, this abandonment is among the main causes of fires in Portugal, which result in fresh ecological damage almost every year, the assessment notes.

Abandoned Land

The increased risk of fire from rural abandonment is largely due to the unmanaged accumulation of vegetation that can fuel the flames, explains Ermitão.

The pastoralists who were once “responsible for managing the land through grazing” have gone, and in their place, unmanaged shrubland and nonnative forests have sprung up, he says.

“When you have abandonment of these lands, it drives the growth of other plants and disorganization of the forests, so if you have a fire, you have more fuel accumulated that is not managed,” Ermitão says.

What’s more, the few domestic grazing animals that remain are managed in a significantly different way.

“They’re not driven,” Prata says, meaning they stay in one place all year long. “You can have paddocks that are completely overgrazed next door to areas with full accumulation of fuel for decades.”

And this fuel accumulation can be significant. A study focusing on the very north of Portugal between 1958 and 1995 found that the decline in agricultural areas and low shrublands and an increase in tall shrublands and forests represented a 20% to 40% increase in fuel accumulation, which, according to the study, suggests “that the abandonment of farming activities is a major driving force of increasing fire occurrence in the region.”

At the same time, human-driven climate change is leading to extreme heat waves that form “the perfect environment for larger, more frequent forest fires,” according to the World Resources Institute.

This creates the perfect storm, where land abandonment and fire-prone species provide the fuel and climate change the catalyst.

The effects of these wildfires can be devastating. Severe burns can result in biodiversity destruction, forest damage, carbon and nutrient cycling disruption, and potential post-fire effects such as soil erosion and debris flows, according to a recent paper co-authored by Ermitão.

They also pose a significant threat to human life and take a serious economic toll on the regions where they occur. The full impact of this year’s fires is not yet known, but last year’s fires, which were a fraction of the size, cost an estimated $420 million, according to a report from the World Bank.

Managed Lands as Adaptation

When it comes to preventing these wildfires, the biggest challenge is land management, says Ermitão.

In an attempt to address this, the Portuguese government has implemented policies that require people to care for their land, protect villages, and manage excess vegetation that could otherwise become fuel for wildfires.

Meanwhile, the few baldios that were re-established following the fall of the Estado Novo are moving towards “mosaic landscapes,” which combine agriculture, pastoralism and forestry in a way that helps control wildfires, according to Skulska. This, she continues, also supports “incomes and more diversity [of] activities,” which could entice people back to these rural areas.

However, not everyone agrees that people should be the ones to manage these landscapes. Human intervention tends to be “systematic and very predictable,” and therefore lacks the nuance needed for healthy ecosystems, says Sara Casado Aliácar, head of conservation at Rewilding Portugal.

Instead, Aliácar explains, we should reintroduce wild grazers to manage these fire-prone ecosystems in a more holistic way.

“[Wild grazers] are reducing biomass while respecting biodiversity” through seed dispersal and the creation of habitats for other creatures like invertebrates and insects, says Aliácar, and “if [wild] grazers are reducing biomass, there are less things to burn.”

What’s more, wild grazers such as European bison and wild horses could also maintain permanent pastures, which are “accumulating organic matter and carbon continuously,” she explains. This helps address the immediate causes of fires by reducing fuel accumulation as well as the underlying catalyst of climate change by sequestering carbon from the atmosphere.

Almost a century since Estado Novo implemented its agricultural campaigns, and more than 50 years since the regime fell, Portugal is still grappling with the consequences of rural abandonment and forest monocultures.

Whether through legislation, community management, or rewilding, the path to recovery is slow and complex — but as the climate crisis drives increasingly severe and frequent fires, it’s more important than ever to confront these underlying vulnerabilities.

Previously in The Revelator:

Anthrax in Zimbabwe: Caused by Oppression, Worsened by Climate Change

Since then his work for National Geographic and other publications, as well as his many books, has taken him all over the world. He’s written about emerging diseases, including HIV and COVID-19, as well as climate change and other threats.

Since then his work for National Geographic and other publications, as well as his many books, has taken him all over the world. He’s written about emerging diseases, including HIV and COVID-19, as well as climate change and other threats.