As a child Diana Doan-Crider loved hearing her grandfather’s tales of the grizzly bears and wolves he saw in the early 1900s while working to build Mexico’s railroads through the mountains. A Tepehuán Indian from Durango Mexico, he told vivid stories, and his knowledge of nature inspired her to become a wildlife biologist when she grew up and to spend decades researching black bears in northern Coahuila’s mountains, just across the Texas border.

That was an important time for black bears, which had all but vanished from Texas in the 1950s following decades of hunting, trapping and habitat loss. The animals started to return to Texas’s Big Bend National Park in the late 1980s. At first it was just a handful of bears, but soon visitors began reporting dozens sighted a year, including females with cubs.

Doan-Crider’s pioneering research, published in 1996, helped confirm what Texas wildlife managers long suspected: Black bears were regaining a foothold in southern Texas, not from other U.S. states but from Mexico.

Mexico has a thriving bear population, thanks to its mountainous expanse and greater cultural acceptance of the animals, both of which also made the recolonization possible, says Doan-Crider, who is now an adjunct professor at Texas A&M University and executive director of a nonprofit called Animo Partnership in Natural Resources.

“Mexico’s bear habitat is so huge, and some local densities are the same as what you’d see in Alaska,” she says. “You can see 25 bears in one day.”

The bears, Doan-Crider and other researchers found, were crossing into Texas from Mexico through the Sierra del Carmen Mountains, which are only separated from the mountains in Big Bend by the Rio Grande River.

Big Bend, which was established in 1944 when there were no bears in the area, is a stunning and geologically diverse landscape of mountains, desert and river that stretches for more than 1,200 square miles along the border where West Texas dips into Mexico. It’s also good habitat for the returning bears, and it quickly became a safe haven for the animals.

Today, with the bears still reestablishing themselves, Texas lists the black bear as a threatened species.

This fledgling recovery could now be in jeopardy, however. Experts worry that any obstacle to the animals’ movement, such as President Trump’s proposed border wall, would set back hard-fought efforts to rebuild the population — especially with climate change intensifying the episodes of drought and wildfire that serve as key drivers for bears expanding beyond their usual range.

“The ability for wildlife to move across that border is so important,” says Patricia Moody Harveson, a research scientist at Borderlands Research Institute at Sul Ross State University. “We would not have black bears in Texas anymore if it wasn’t for that transboundary movement across that border.”

It’s not clear whether the Trump administration plans to construct the border wall through Big Bend, although it continues pressing forward with plans to build the wall through the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge and a 100-acre butterfly refuge.

The National Park Service declined a request to be interviewed for this story.

A volunteer ranger at the park, who did not want to be identified, told The Revelator that talk of the wall is, “all buttoned up.” But he said it “goes against everything the park stands for” and wondered how a wall could be built when heavy machinery is banned from the park, even for the removal of old telephone poles.

Bears, of course, are only one of many species, from reptiles and amphibians to bighorn sheep, which would be affected by the proposed wall. Beyond Texas, conservationists recently claimed that building the wall would be “game over” for recovering jaguar and ocelot populations in Arizona.

Jonah Evans, state mammalogist at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, agrees with Harveson that, “when it comes to bears, being able to travel across large areas is important to recover their populations and thrive in a landscape as challenging as West Texas.”

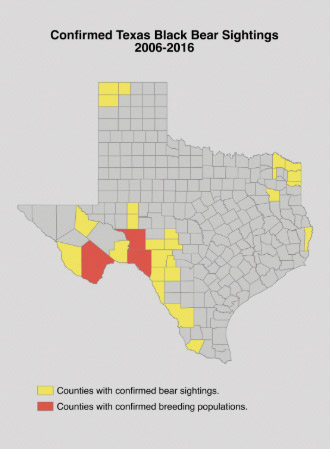

Evans can’t say how big the bear population is in the state, but he says they’ve mapped breeding populations in just three of Texas’ 254 counties.

“Right now, we have very few,” he adds. “It’s a pretty isolated population.”

Bears are tough to count, because they cover huge distances and are expensive to catch and monitor. Texas Parks therefore relies on data from trail cameras and from voluntary reports of bear sightings by ranchers, such as at deer feeders.

Based on those reports, Evans says Big Bend National Park is “clearly one of the core breeding populations that we have.”

He adds, “If you don’t have breeding, you don’t have bears.”

Climate Change and Cross-border Movement

Extreme weather events appear to be a key driver for bears crossing the border, according to Doan-Crider’s research.

“We’re now looking at how drought and events like wildfires are a driving mechanism for expanding a bear population,” says Doan-Crider. “Normally females might not leave their home range, but once those droughts hit, once wildfires come in, they will cover huge distances to find some habitat.”

Her research correlates maps of food sources like oak trees (acorns) and prickly pear with bear movements, documenting that female bears will travel twice as far as in times of drought, or what she calls the “threshold of misery.”

Black bears can have enormous ranges during these periods, as great as about 380 square miles, she says.

This can drive bears from Mexico into the United States or force them to journey in the opposite direction. Other researchers, including Dave Onorato and Raymond Skiles, the recently retired wildlife biologist for Big Bend, have also documented these border crossings during drought. At one point in the early 2000s, when food was scarce in Big Bend, all the bears left for Mexico and then returned a year a half later. Similarly, Harveson noted that two bears the Borderlands Research Institute was radio-tracking crossed over into Mexico during the severe 2012 drought.

Invisible Wall

As “horrified” as she is by the proposed border wall, Doan-Crider says she’s more concerned about what she calls the “invisible wall,” or the lack of social acceptance and lack of preparation bears hit when they cross into Texas.

Most wildlife managers and researchers are focused on Big Bend, but Doan-Crider says she thinks bears are also crossing into Texas farther east, from the mountains just south of Laredo, where Mexican land cooperatives are protecting bears. They don’t stand a chance on the U.S. side, she says, because of the likelihood that they’ll come into contact with humans who aren’t used to living with bears, or with landowners who have deer-hunting operations.

Meanwhile, Harveson says the breeding population at Big Bend appears to be spreading into the Davis Mountains, about 150 miles to the north. That could also put them at risk.

“As bears move into areas they haven’t been in for more than 50 years, we look for that potential for human-bear conflict,” she says. The Borderlands Research Institute plans to study the corridors that bears are using to traverse this distance, as well as their use of habitat and movements within the Davis Mountains. “We’d like to help make the adjustment easier.”

Doan-Crider agrees that more steps need to be taken to protect the black bears that have returned to their former range.

“If Texas wants to do something about bears, they should be putting a lot of money into educating the public,” she stresses.

Doan-Crider says the question of the wall, and the bigger question of bear recovery, is more about, “Do you want to have bears in Texas?”

If the answer is yes, then keeping the border open — especially at Big Bend — is vital.

![]()

1 thought on “To Survive in Texas, Black Bears Need an Open Border”

Comments are closed.