It’s that time of year: Winter is waning, giving us an opportunity to rethink our gardens and landscaping from an environmental, sustainable perspective. We’ve got some inspiring recent and forthcoming books to help you realize those goals.

Whether you’re a beginner or expert home gardener, a participant in a community garden, or have responsibility for a park or other public space, these books offer practical advice for weeding out nonnative species and establishing sustainable public spaces, home gardens and landscaping that showcase local plants and attract wildlife to pollinate and coexist with human communities.

Our list includes practical guides, firsthand success stories, and uplifting approaches to gardening and landscaping at home and beyond. We’ve included each book’s official descriptions, and the links for each title on the publishers’ websites. You should be able to find or request any of these books through your local booksellers or libraries — or maybe the local garden club, further supporting your community.

How Can I Help? Saving Nature With Your Yard by Douglas W. Tallamy

Tallamy tackles the questions commonly asked at his popular lectures and shares compelling and actionable answers that will help gardeners and homeowners take the next step in their ecological journey. Tallamy keenly understands that most people want to take part in conservation efforts but often feel powerless to do so as individuals. But one person can make a difference, and How Can I Help? details how.

Whether by reducing your lawn, planting a handful of native species, or allowing leaves to sit untouched, you will be inspired and empowered to join millions of other like-minded people to become the future of backyard conservation. (Available April 8.)

Grass Isn’t Greener: The Everyday Conservationist’s Guide to Bringing Nature to Your Yard by Danae Wolfe

Rooted in 20 practical steps that anyone can take starting today, Grass Isn’t Greener demonstrates how small changes in your yard or garden can create lasting impact for the planet: From leaving your leaves to selecting eco-friendly holiday decorations; from eliminating light pollution to attracting wildlife; from saving seeds to devoting even a small patch of lawn to native plants. With easy-to-follow advice and real-life examples, conservation educator Danae Wolfe will help you appreciate the new life you’ve attracted to your yard. A companion for new homeowners, renters, and gardeners, Grass Isn’t Greener is a resource for anyone looking for little ways to make a big difference — and to have fun doing it. (Available May 13.)

Bad Naturalist: One Woman’s Ecological Education on a Wild Virginia Mountaintop by Paula Whyman

With humor, humility, and awe, one woman attempts to restore 200 acres of farmland long gone-to-seed in the Blue Ridge Mountains, facing her own limitations while getting to know a breathtaking corner of the natural world. When Paula Whyman first climbs a peak in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in search of a home in the country, she has no idea how quickly her tidy backyard ecology project will become a massive endeavor. Just as quickly she discovers how little she knows about hands-on conservation work.

In Bad Naturalist readers meander with her through orchards and meadows, forests and frog ponds, as she’s beset by an influx of invasive species, rattlesnake encounters, conflicting advice from experts, and delayed plans — but none of it dampens her irrepressible passion for protecting this place. With delightful, lyrically deft storytelling, she shares her attempts to coax this beautiful piece of land back into shape. It turns out that amid the seeming chaos of nature, the mountaintop is teeming with life and hope.

Survival Gardening: Grow Your Own Emergency Food Supply, From Seed to Root Cellar by Sam Coffman

Learn how to grow your own food supply and be prepared just in case of an emergency with this essential guide by a survival skills expert. Author Sam Coffman shows you how to select and grow the most valuable crops in the least amount of space, using few or no store-bought amendments. He also shows you how to grow food quickly (in as little as five days) in an emergency, choose and plant perennial food plants for longer-term harvest, grow mushrooms, forage from the backyard, and store food for the long term. Great for adults and teens to take back control from big food suppliers’ gouging.

Indoor Kitchen Gardening for Beginners by Elizabeth Millard

In this condensed, beginner-friendly edition of Indoor Kitchen Gardening, you’ll discover it takes just a few dollars and a few days for you to enjoy fresh, healthy produce grown indoors. Accent home-cooked meals with your own carrots, lettuce, herbs, and microgreens, all cultivated right inside your home.

Millard teaches you how to grow dozens of different edible plants — from sprouts and mushrooms, to tomatoes, peppers, and more — on a sunny windowsill, under grow lights, or even in a basement, where you won’t have to worry about pests or climate unpredictability.

The Regenerative Landscaper: Design and Build Landscapes That Repair the Environment by Erik Ohlsen

Created for beginner gardeners and large-scale permaculturists alike, this step-by-step guide starts with your ideas and educates readers on what and how to cultivate seeds, plants and trees confidently.

More than just a guide to landscaping, The Regenerative Landscaper is a motivational read in which Ohlsen addresses climate change, species extinction, and ecological collapse with a sense of encouragement that each of us can become stewards of the land by installing healthy ecosystems in our own yards. Full of hope and tangible action, readers can feel empowered to restore planetary health one garden at a time.

Climate-Wise Landscaping: Practical Actions for a Sustainable Future, Second Edition by Sue Reed and Ginny Stibolt

Predictions about future effects of climate change range from mild to dire — but we’re already seeing warmer winters, hotter summers, and more extreme storms. Proposed solutions often seem expensive and complex and can leave us as individuals at a loss, wondering what, if anything, can be done. Sue Reed and Ginny Stibolt offer a rallying cry in response — instead of wringing our hands, let’s roll up our sleeves. Based on decades of the authors’ experience, this book is packed with simple, practical steps anyone can take to beautify any landscape or garden, while helping protect the planet and the species that call it home.

The Climate Change Garden, Updated Edition: Down to Earth Advice for Growing a Resilient Garden by Sally Morgan and Kim Stoddart

It’s no longer gardening as usual. Heat waves, droughts, flooding, violent storms…and gardeners are feeling the effects. Certain pests stay active until later in the season, many plants bloom earlier, soils are eroding rapidly. What’s a gardener to do?

Learn how to protect a garden from climate extremes, exotic pests, invasive weeds, and more. The Climate Change Garden is the first book to reveal which types of gardens are better suited to deal with such extremes and which techniques, practices, and equipment can be used in our gardens to address the issues. No matter where on the planet you live, the climate and weather are changing fast, and our gardening practices need to catch up.

Gardening in a Changing World: Plants, People and the Climate Crisis by Darryl Moore

Moore explores how gardens can be better for humans and all the other lifeforms. Recent developments in horticulture and plant science show us how to think about plants beyond purely aesthetic concerns, and to adopt more holistic approaches to how we design, inhabit and enjoy our gardens. He looks at today’s garden design and suggests positive ways to change our behavior for sustainable ecological horticulture.

The Climate Change-Resilient Vegetable Garden: How to Grow Food in a Changing Climate by Kim Stoddart

Stoddart outlines a clear path to build resilience in your vegetable plants, your soil — and yourself. Providing actionable tasks that reduce resource use, stabilize the garden’s ecosystem, and regenerative solutions to the most challenging issues faced by gardeners, Kim comes to the rescue with advice to help you adjust your gardens with ease.

Resilient Garden: Sustainable Gardening for a Changing Climate by Tom Massey

Award-winning garden designer Tom Massey shares essential tips on how to analyze your garden looking at everything from soil type to sun exposure, before recommending practical projects and plant choices that will be perfect for your plot. Discover how a hedge can reduce noise and trap pollution, how a patio affects waterlogging, how to harvest your rainwater, and much more.

Revered Roots: Ancestral Teachings and Wisdom of Wild, Edible, and Medicinal Plants by LoriAnn Bird

With Indigenous Métis herbalist LoriAnn Bird as your guide, connect with the ancestral wisdom of over 90 wild edible and medicinal plants from across North America.

A purposeful and powerful reference to the lessons, nourishment, healing, and history of our “plant teachers,” Revered Roots shares guidance on exploring, gathering, and reclaiming these long-revered plants as food and medicine.

Reclaiming our natural rhythms and connections to the earth we walk on is essential to our health and well-being, both as individuals and as a community. One simple way to do that is by appreciating, respecting, and seeking to understand the plants around us.

Now that you’ve focused on your green spaces, here’s another way to enjoy and learn from them:

The Urban Naturalist: How to Make the City Your Scientific Playground by Menno Schilthuizen

Imagine taking your smartphone-turned-microscope to an empty lot and discovering a rare mason bee that builds its nest in empty snail shells. With a team of citizen scientists, that’s what Menno Schilthuizen did — one instance in the evolutionary biologist’s campaign to take natural science to the urban landscape where most of us live today. In this delightful book, The Urban Naturalist, Schilthuizen invites us to join him, to embark on a new age of discovery, venturing out as intrepid explorers of our own urban habitat — and maybe in the process doing the natural world some good.

Beyond technology, this book holds the promise of reviving the citizen scientist — rekindling the spirit of the Victorian naturalist for the modern world.

Happy reading and gardening — and let us know how it goes (or grows). Send your success stories, tips, and other book recommendations to [email protected].

For hundreds of additional environmental books — including several on farming and plants — visit the Revelator Reads archives.

Previously in The Revelator:

Urban ‘Microrewilding’ Projects Provide a Lifeline for Nature

In addition to the emotional text, the poems use the visuals to set or continue the mood and narrative. Some sequences go on for several pages without a single word — poetry by way of image and imagination. It’s a powerful experience that deserves our attention while it attempts to heal our souls. (Available March 25.)

In addition to the emotional text, the poems use the visuals to set or continue the mood and narrative. Some sequences go on for several pages without a single word — poetry by way of image and imagination. It’s a powerful experience that deserves our attention while it attempts to heal our souls. (Available March 25.)

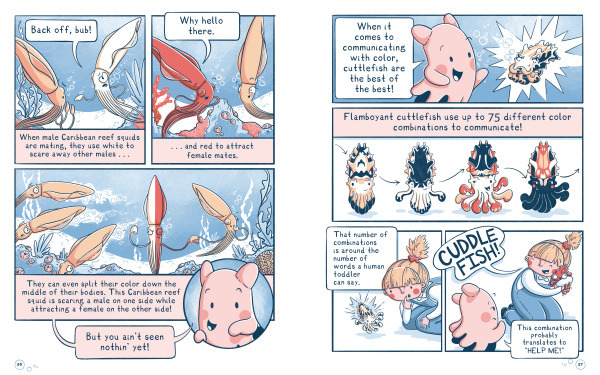

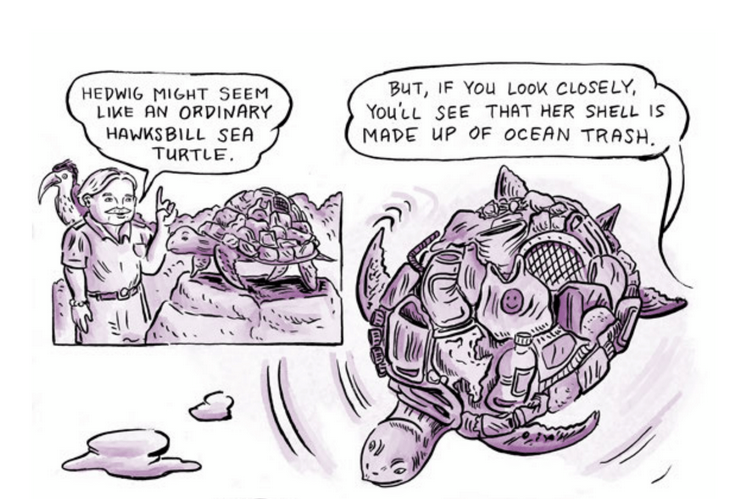

Quite simply this is science comics done right, and it could help any young reader gain an appreciation for the ocean and everything that lives in it. It’s also apparently

Quite simply this is science comics done right, and it could help any young reader gain an appreciation for the ocean and everything that lives in it. It’s also apparently

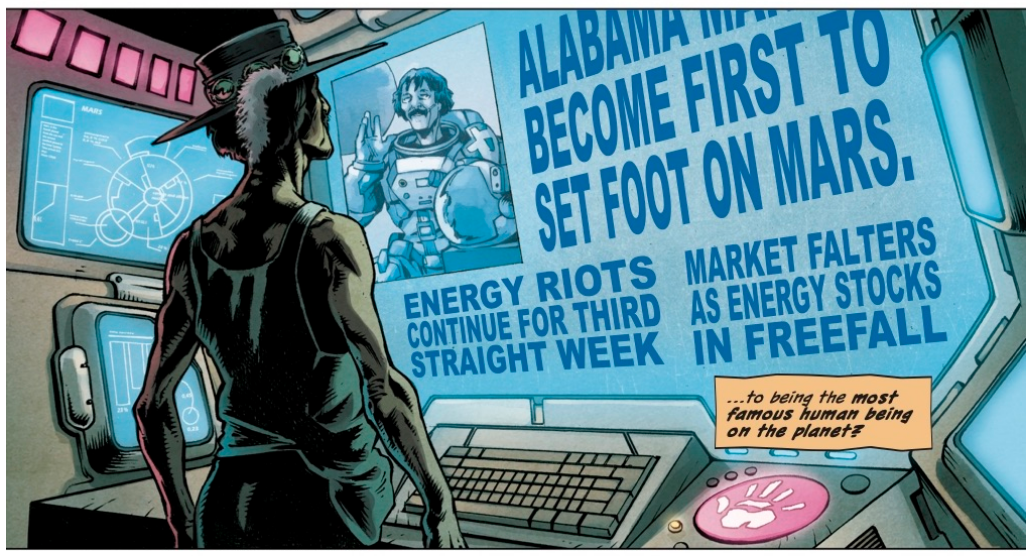

The weightlessness of space, the company tells him, will slow his cancer’s growth, but his inevitable death remains part of the plan. He’s disposable — a human flag to plant in the soil, useless to his corporate masters after he completes his mission. As long as he gets there first and fast, extraction crews can follow, and the energy (and money) will flow.

The weightlessness of space, the company tells him, will slow his cancer’s growth, but his inevitable death remains part of the plan. He’s disposable — a human flag to plant in the soil, useless to his corporate masters after he completes his mission. As long as he gets there first and fast, extraction crews can follow, and the energy (and money) will flow.

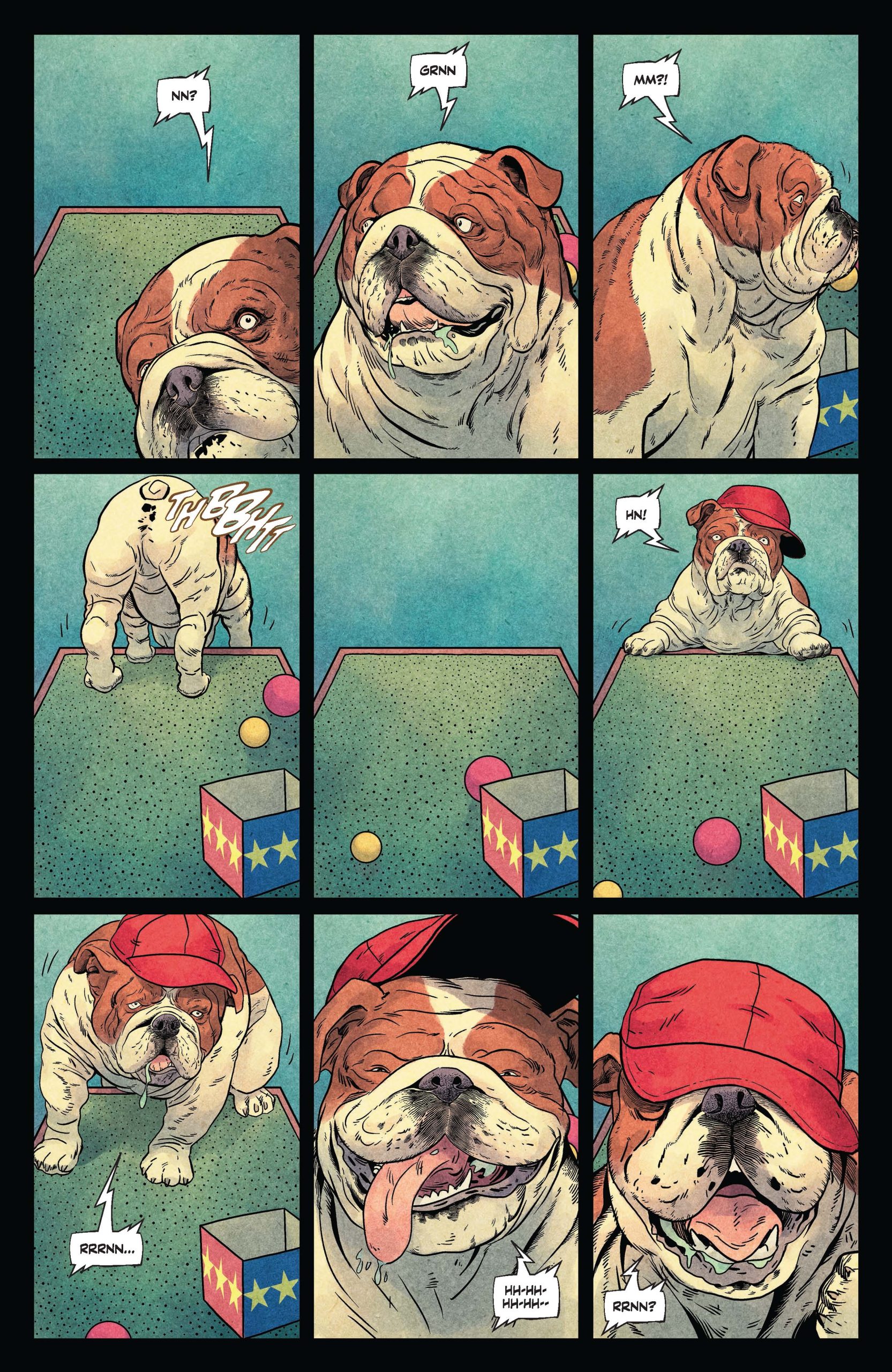

Published as five issues starting in 2023, long before the election, this new collected edition packs an extra powerful wallop now that Trump is back in office. It’s not really an environmental book, although the early pages contain several strong messages about animal rights. It is, however, a brutal examination of our times and a cautionary tale of power and personality.

Published as five issues starting in 2023, long before the election, this new collected edition packs an extra powerful wallop now that Trump is back in office. It’s not really an environmental book, although the early pages contain several strong messages about animal rights. It is, however, a brutal examination of our times and a cautionary tale of power and personality.

Fitzgerald, a frequent New Yorker and New York Times cartoonist, fills the pages of this book — her first foray into fiction — with lush brush strokes and an appreciation for nature (and some underlying, if softly spoken, contempt for what humans can do to it). She’s developed some interesting characters, especially Hazel, who is full of doubts and fears and makes mistakes but uses her brain and keeps moving forward. Her animal characters are both fully drawn and a little too convenient (Nina has a few abilities that further the plot but make little biological sense).

Fitzgerald, a frequent New Yorker and New York Times cartoonist, fills the pages of this book — her first foray into fiction — with lush brush strokes and an appreciation for nature (and some underlying, if softly spoken, contempt for what humans can do to it). She’s developed some interesting characters, especially Hazel, who is full of doubts and fears and makes mistakes but uses her brain and keeps moving forward. Her animal characters are both fully drawn and a little too convenient (Nina has a few abilities that further the plot but make little biological sense).