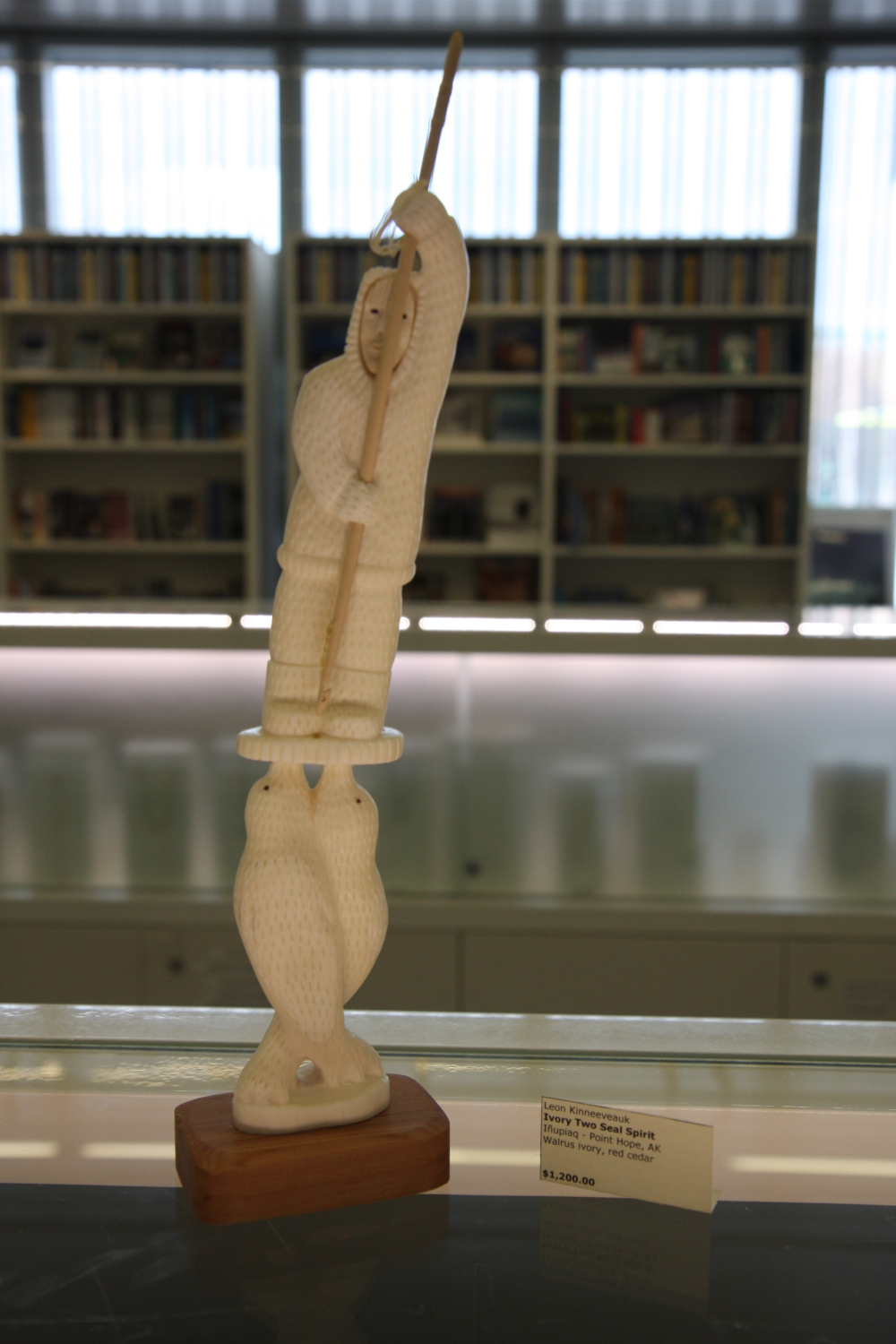

“You don’t want to get it from headhunters,” Leon Kinneeveauk tells me as we maneuver around his crowded art studio in downtown Anchorage. Tools, bones, and unfinished carvings extend over every work surface, covered in a thin layer of white dust.

Kinneeveauk, an Inupiaq artist who specializes in carving walrus ivory, grew up in the remote Point Hope, a northwestern Alaskan village accessible only by plane or boat. His Anchorage gallery, Arctic Treasures, is a trove of work of master craftsmen from around the state. At the back of the shop, which he took over from its previous owner last year, is a growing studio space where he and artists work on native handicrafts, from whale baleen baskets to delicate bird figurines and walrus ivory carvings like the ones he makes himself.

Kinneeveauk is careful about where he sources his walrus ivory. He has to be. In northwest Alaska large colonies of Pacific walrus now regularly haul themselves out onto land — a phenomenon tied to the loss of sea ice due to climate change that has led to new threats for the massive marine mammals. When these walrus are vulnerable on land, people have killed them and salvaged only the tusks.

“Headhunting,” as this is known, is a violation of the Marine Mammal Protection Act, under which Indigenous people can hunt walrus but must make use of the whole animal. In recent years four hunters from Kinneeveauk’s community were charged with shooting and headhunting eight walruses hauled out on a beach at Cape Lisburne. The men’s actions during two separate hunts caused herds to stampede, resulting in the death or injury of at least two dozen additional walrus, about half of which were calves.

Catastrophic stampedes such as these would not occur on ice floes, where animals can escape into the water if disturbed.

The men were sentenced in a case of restorative justice, under which they must perform services to benefit their community, such as hunting for the subsistence needs of elders and delivering presentations in coastal villages on hunting ethics and the legal duty to take animals in full.

Kinneeveauk takes his own “full use” responsibility to another level in his art: He uses even the fine ivory dust, created while he carves with power tools, to fill in cracks in his carvings. The piece he’s working on as we visit his studio is a lithe fisherwoman. The sound of his electric drill fills the space with a hum as he shows me his work. While he carves, he wears protective goggles and a mask. As I watch, I can sense the walrus bone dust in the air.

Alaska Native artists like Kinneeveauk, who use Pacific walrus ivory, have been plying their trade for centuries, but now they’re up against two intensifying threats: climate change and crime.

Walrus hunting, including at terrestrial haul-outs, is managed by the Eskimo Walrus Commission and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Even when walrus ivory is responsibly sourced in accordance with hunting ethics and regulations, sales of carvings are now being forestalled and overshadowed not just by recent illegal activity in Alaska but also poaching on the other side of the world.

Arctic Treasures itself was recently at the center of some of these types of crimes. In March of this year the gallery’s previous owner, Lee John Screnock, who is not Inuit, was indicted for selling walrus ivory carvings that he had carved himself and falsely marketed as “Native-carved.” Screnock further violated the Marine Mammal Protection Act by selling polar bear and walrus bones, including skulls and oosik (walrus penis bone). The case puts Kinneeveauk, who acquired the store in June 2018, under additional pressure to improve the shop’s reputation.

Another ongoing case involves a man who outsourced walrus ivory carving all the way to Indonesia, re-imported the finished pieces back to Alaska, and sold them to tourists alighting from cruise ships in Skagway, a popular destination that was once a Gold Rush boomtown. There are other cases of art being crafted overseas, for example jewelry manufactured in factories in the Philippines, then imported and sold in the United States under the label “Native-made.”

Ironically the poaching threat to walruses may be increasing in part because other target species’ populations are under poaching pressure.

“As elephant populations continue to be decimated, walrus, narwhal or other ivory-carrying species could become the next targets for unscrupulous and large-scale commercial operations,” says Steven Skrocki, deputy criminal chief in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Alaska, which had legal authority in the Point Hope case and now in both the Arctic Treasures and Skagway cases, among others.

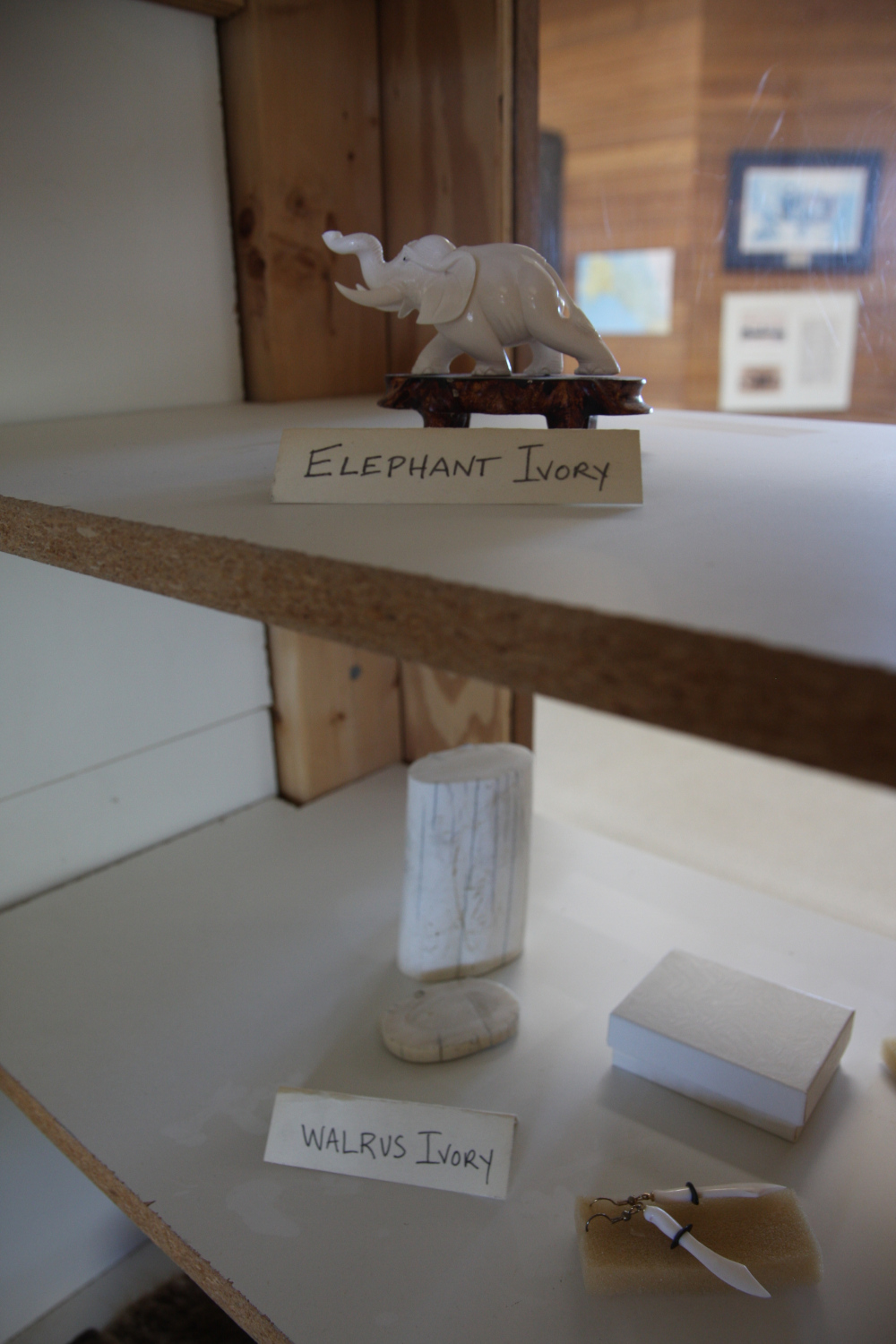

This means that Kinneeveauk is also contending with wider controversies, including blanket ivory bans being enacted by some U.S. states as an outcome of elephant poaching in Africa. The bans have been proposed and decreed because of the difficulty in distinguishing ivories from elephants and similar tusk-bearing species such as walruses and even extinct mammoths.

Amid the huge, dramatic changes facing the Arctic, the reverberations of the race to save another ivory-bearing species on the other side of the world, and the crime that too often accompanies the commercialization of wildlife products, can the traditions of Inuit carvers who use Pacific walrus ivory be preserved?

Walruses are the only living member of an entire family of marine mammals distinguished by their upper canines. Their similarly semi-aquatic relatives — sea lions and fur seals — do not have “ivory,” which in walruses is really two canines long enough to be called tusks or “morse.” The tusks can grow as long as 40 inches. Because walruses use them to lift themselves out of the water onto sea ice, the animals’ scientific name Odobenus rosmarus translates into “tooth-walker.”

Pacific walrus, one of two walrus subspecies, inhabit the waters around the United States and Russia and “wander” into Canada and Japan. Unlike Atlantic walrus, which are largely sedentary in their habits, Pacific walrus are highly migratory. Pacific walrus are on the watchlists of wildlife agents and government officials in Alaska because of the high street value of their ivory tusks and the growing number of terrestrial haul-outs, where they are vulnerable to disturbance.

While walrus harvest is currently considered legally sustainable, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service walrus biologist Joel Garlich-Miller says he’s still concerned about what the future holds given how rapidly sea ice is shrinking and shipping traffic is increasing. The number of walrus now — estimated at some 250,000 — is the same number taken over just a 16-year period by European whalers for oil, tusks and hides in the second half of the 19th century. It took 100 years for walrus to recover to pre-European commercial harvest levels.

Among the biggest current concerns today, says Garlich-Miller, is disturbance at coastal haul-out sites.

“There are tens of thousands of walrus hauling out at locations in Russia and the U.S.,” he says. “On land they’re very susceptible to human disturbance in the form of planes, boats and hunting.”

What makes these large haul-outs risky is that walrus have one direction to go: toward the water. If adult walruses panic and try to rush to safety, calves can get crushed and injured.

“A single stampede can cause tens or even hundreds of animals to die,” Garlich-Miller says. In some years trampling mortalities can exceed the entire legal harvest of Alaska.

This is happening more frequently, and it doesn’t just endanger the walruses. In the Russian town of Vankarem, dogs and polar bears are drawn to walrus carcasses following stampedes, raising the likelihood of negative interactions between people, their domestic animals and wild carnivores.

In an attempt to minimize these risks, Native leaders in Alaska and Chukotka are working to discourage the practice of hunting walrus at haul-outs. Another alternative they’re promoting involves hunting only with silent bows or spears instead of loud rifles to reduce the likelihood of causing the larger colony to panic.

“The future of walrus has not been written yet,” he says optimistically. “There are things we as a society can do to mitigate, including allowing animals to adapt to new habitat areas, protecting animals at haul-outs and keeping subsistence harvest levels sustainable.”

He adds, “There will always be some opportunists, but most hunters have a strong ethic.”

Could blanket ivory bans and other legislative attempts to solve these problems actually harm Native carvers?

That’s the contention of some Alaska lawmakers, who this past March introduced a federal bill seeking to block other states from banning the sale of walrus ivory, whale bone and other marine mammals carved by Alaska Native artists.

The bill, entitled the “Empowering Rural Economies through Alaska Native Sustainable Arts and Handicrafts Act,” aimed to preempt state ivory bans from including marine mammals, as well as extinct mammoth and mastodon, which are also carved by Alaska Natives. It hews closely in content to a previously proposed bill called the “Allowing Alaska Ivory Act,” a name legislators dropped in an attempt to make the bill more palatable in our ivory-averse times.

“Allowing the sale of ivory has a negative connotation,” says Kate Wolgemuth, rural advisor to Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-Alaska), who sponsored the Act (it has not moved beyond the submission stage). “States have been enacting blanket ivory bans because they’re worried about African elephant ivory poaching. As a result, they don’t distinguish between different types of ivory.”

Blanket ivory bans, according to Wolgemuth, may cause residents to worry about buying, owning and bringing home legally acquired ivory from Alaska. “These laws go against the MMPA, which explicitly protects Alaska Native artists’ right to carve and sell marine mammal ivory,” she says. “These bans were passed without Alaska’s input.”

“Walrus ivory carving is about culture, not commerce,” she adds.

The sale of any ivory has been prohibited by California, Hawaii, New York, and New Jersey among other states. Wolgemuth says she now avoids traveling with walrus ivory herself, as each state’s ban differs slightly.

Meanwhile bones from extinct mammoths have also been proposed for trade bans. The issue is currently being studied by the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species, an international treaty that regulates the sale of threatened wildlife — the first extinct species being considered for a trade ban.

Some conservationists and researchers fear that African elephant ivory can be mislabeled and smuggled as mammoth, allowing illegal products to be disguised in the legal marketplace. But Wolgemuth says Sullivan’s office believes that having a substitute for elephant ivory in the form of mammoth can help rather than hurt African elephants. Mammoth, she says, should be free for everyone to use.

The importance of mammoth and mastodon carving in Alaska varies from community to community, says Vera Metcalf, director of the Eskimo Walrus Commission. “For Shishmaref, mammoth is important, but on St. Lawrence Island [where Metcalf is from], we have neither mammoth nor mastodon but could trade our walrus for it.”

At the Anchorage Museum I find the work of several Native carvers, including Kinneeveauk, for sale in the gift shop.

Another artist whose work is sold there is Jerome Saclamana, an Iñupiaq carver from Nome. He makes clear that walrus tusk carving has given him a living. “I’m not getting rich from it but I’m able to practice what my ancestors did, only in a more modern way,” he says, referring to power tools.

Like Kinneeveauk, Saclamana also now lives in Anchorage as “there’s more of a market for my carvings here than in Nome.” Still, he says the price he can currently charge is 25 percent less than just a few years ago. He theorizes consumer confusion over what ivory is legal to buy has caused the market and prices to shrink.

Joining the conversation, Aaron Tolen, an education intern at the Anchorage Museum, tells me he’s “probably related to Saclamana. My mother is from Nome.”

Tolen brings up a new issue, asking Saclamana if he’s noticed any differences in walrus tusk length and density now compared with the past. Tolen’s studying the issue. He thinks cracks in walrus ivory are caused by reduced tusk density, possibly because climate change is causing shifts in walrus diet.

“Walrus are shallow-water bottom-feeders,” he explains. “Now, with ice receding, walrus must dive deeper down to get shellfish and they’re not getting as much food. Less nutrition means less dense tusks that are more fragile and crack more easily.”

But Saclamana attributes the change to young hunters not being careful enough when hunting and therefore breaking tusks, either during the hunts or when separating the teeth from the walrus skull. “Nowadays new hunters are not taught as well and I see more harvested tusks that are chipped,” he says. “I see more mishandled tusks now than before.”

When I visit Kinneeveauk’s shop and studio again, he says walrus ivory has always had some marks and cracks in it from walruses using their tusks for foraging. The tusks, he says, tell a story of a walrus’s life. “Some walrus even hunt seals.” He shows me a tusk stained with what he says is seals’ blood. “This one was a seal hunter.”

While he feels cracks in ivory are not the fault of a new generation of walrus hunters, he does show me one tusk with a bullet hole where the impact shattered the ivory like a rock cracking a windshield. “This was the hunter’s first hunt,” he says. “I still bought the tusk from him. I can fashion it into earrings.”

When I ask Garlich-Miller about cracks in ivory, he offers yet a fourth explanation. “Female ivory grows more slowly and is denser as a result,” he says. Although adult male tusks are larger, the ivory often has linear cracks. “That’s why there was historically a premium on the market for female tusks.”

What I take away from this is that even as the threats of climate change rise, we don’t have all the insights yet about how wild animals are responding. Traditional ecological knowledge keepers might agree as much as some scientists: sometimes not at all.

For the time being, Pacific walrus are not protected under the Endangered Species Act, although the Fish and Wildlife Service did find that protection was warranted in 2011. While the population appears to be large and healthy at the present time, shrinking sea ice habitat is expected to cause the population to decline over time, Garlich-Miller says.

Even without that potential protection, Garlich-Miller continues working with the Eskimo Walrus Commission to minimize disturbances at terrestrial haul-outs. For example, they work with the Federal Aviation Administration and the U.S. Coast Guard to steer air and boat traffic away from haul-outs to reduce the potential for stampedes.

Then there’s the threat from individuals, although it remains unquantified. “I don’t want to minimize the risk of poaching, as it can always spring up,” he says. “I also don’t know what’s happening in Russia.” He says some of his former colleagues who were monitoring the situation there are no longer in their positions, so information on what’s happening in Russia has grown scarce.

But poaching does seem to be occurring. Last year more than 400 walrus ivory tusks, presumably from populations in Russia, were seized in China in a shipment that also contained mammoth, narwhal and elephant ivory, antelope horn, and bear gallbladders and teeth.

Moving forward, Garlich-Miller notes that collaboration, monitoring and a commitment to following the law will help sustain both walrus and traditions. That’s where he focuses most of his efforts. “Today, I’m more of an outreach and people person,” he says. A walrus ambassador, I suggest.

If the Pacific walrus ever gains Endangered Species Act protection, exceptions will remain in place for Native subsistence hunters and artisans, just as they currently exist under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, says Andrea Medeiros, public affairs specialist with the Fish and Wildlife Service office in Alaska.

Even today most carvers already make sure to source their ivory responsibly and make a case against wanton waste. Saclamana, the carver from Nome, lists for me the many ways walrus bodies can be employed, including for food. “The stomach is used for drums, and I even use the whiskers in my carvings.” An Anchorage Museum exhibit expands on that, displaying information on how walrus intestines can be cooked or frozen to make everything from waterproof parkas to boat shells and spray skirts for kayaks.

Diversifying to other materials may also play a part in protecting both walruses and carvers. Saclamana says that as he gets older he finds himself tiring of hearing the sound of power tools while he carves. He’s applied for a grant to learn how to carve wood instead.

Kinneveuk, meanwhile, is starting a nonprofit, The Native Artist Alliance, which he says will ensure that his studio remains both safe and sober. “The space gets people off the streets,” says Kinneeveauk, who’s self-rehabilitated with the help of art. It will not, he adds, be exclusive to Alaska Native persons. “We already have two non-native artists, and as long as they don’t touch the ivory, they’re welcome here.”

Many of the experts I spoke with told me it’s important that Alaska Native artists and craftspeople not find themselves pitted against conservationists, and that there’s mutual respect for the common cause of protecting walrus and Inuit traditional food and culture into the future.

But that future for people, culture and walruses remains at risk as the climate continues to heat, a message visible in a short film called “The Walrus” that plays on a continuous loop at the Anchorage Museum.

In the film a hybrid walrus-man appears despondent — something’s lacking from his life. Land-enslaved, he repeats a dull routine while striving for self-recognition in his bathroom mirror. At last, the walrus-man steps onto a beach, looks nostalgically out at sea, and plunges in. Although he’s finally in the water, he’ll find there isn’t much ice left to tooth-walk on.

Author’s note: Since reporting for this story was conducted in Alaska, budget cuts made by the state governor resulted in the temporary closure of the Alaska State Council on the Arts, including its Silver Hand Program, which offered authentication for Native handicrafts. The Silver Hand seal was intended to show that materials were legally sourced and carved. It is unclear if this authentication program will persist.

![]()

1 thought on “Climate Change and Crime: New Pressures for Pacific Walruses and Alaska Native Artists”

Comments are closed.