The Place:

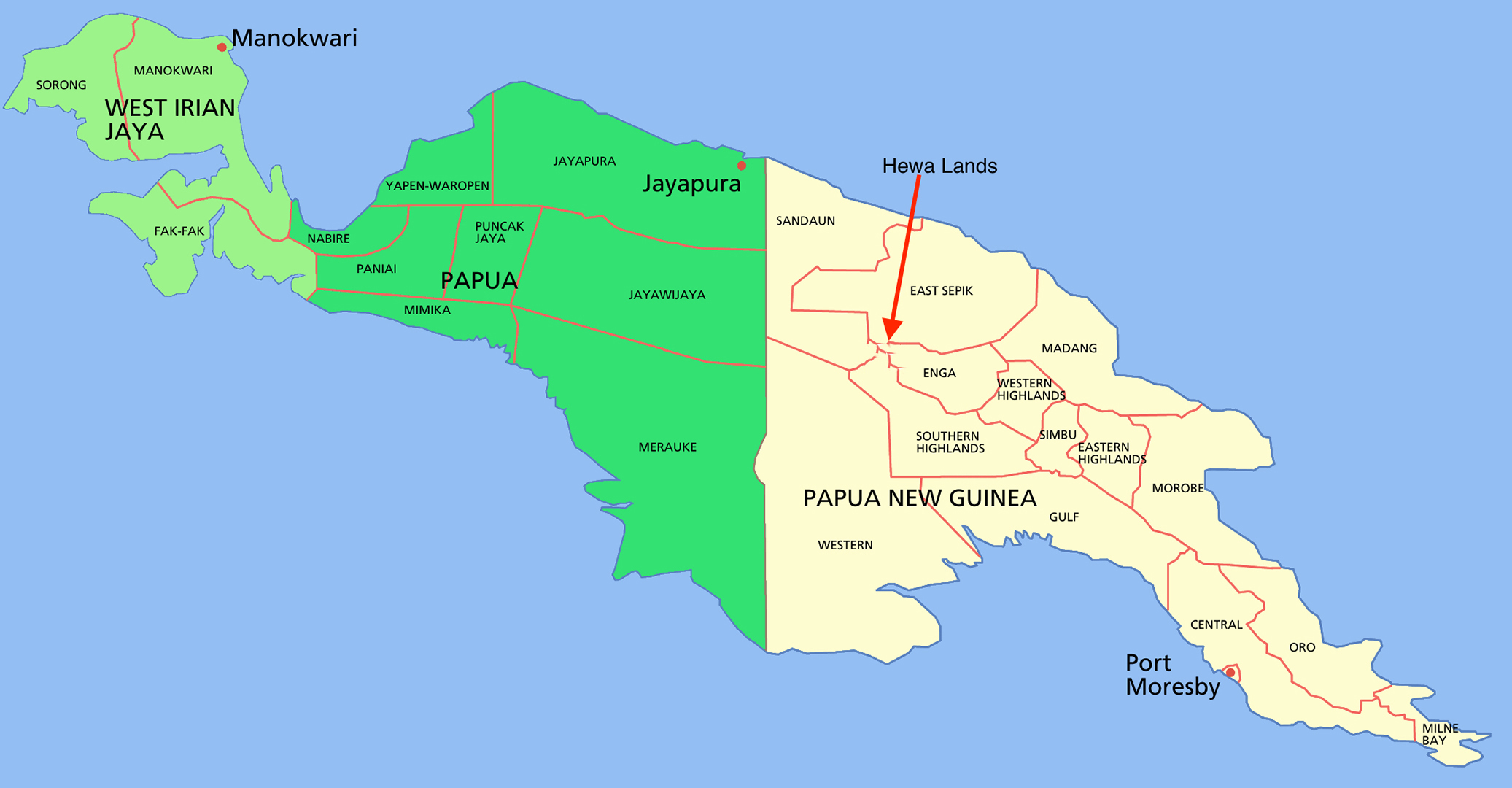

Stretching northward from Papua New Guinea’s Central Range is a globally significant wilderness area located along the riverine systems that mark the intersection of the Central Range and the Star Highlands. Here the Lagaip and OK Om Rivers combine to form the Headwaters of the Strickland, the major tributary of the Fly River. It’s home to biodiversity that rivals that of the Amazon, is one of the least explored regions on Earth, and is part of the largest intact forest ecosystem in the Pacific.

Why it matters:

The Headwaters of the Strickland is part of the limestone district that runs through the center of the island of New Guinea. This is the largest tract of karst topography in Papuasia.

In 1993 an international team conducted a national Conservation Needs Assessment for Papua New Guinea. They declared that this region is:

-

- A “major terrestrial unknown.”

- A national conservation priority.

- Vital to the health of the Gulf of Papua.

The Headwaters remains virtually unexplored. In 2008-09 a Rapid Biological Assessment —conducted by Conservation International in conjunction with the Papua New Guinea Department of Environment and Conservation and the Papua New Guinea Institute of Biological Research — garnered international attention when it found 50 species new to science. Since this was the first systematic scientific exploration of this region, there are undoubtedly more discoveries to be made and even more positive publicity to be generated for Papua New Guinea.

The health of these forests is vital not only to the Indigenous Hewa people but also to the continued viability of New Guinea’s coastal ecosystems and reefs — unique marine ecosystems that rely on the pristine waters delivered from these uplands.

The threat:

The greatest threat is the often-discussed development of a road system that would connect the Headwaters to highlands. Currently the Headwaters is roadless and has no navigable rivers. However, because these forests are extensive and their mineral potential is great, there are persistent rumors of plans to build a road to connect this region to the highlands. Any easy connection to the highlands will likely lead to deforestation, mineral exploration, and a surge in migrants that will overwhelm local landowners and destroy these globally significant forests.

Who’s protecting it now:

The current stewards of the Headwaters of the Strickland River are among Papua New Guinea’s most remote societies: the Hewa. Since 2005 the Hewa have worked to formally protect their lands through the Forest Stewards Initiative. The Forest Stewards use traditional knowledge to develop conservation plans for their land.

I have assisted the Hewa with the documentation of their traditional environmental knowledge and building an organization of local landowners capable of protecting their legacy of biodiversity stewardship for future generations. Together we have worked to demonstrate the effectiveness of tradition as a conservation tool and gazette their lands. We are now working through the political process to formally establish the conservation status of the Headwaters and find a sustainable funding mechanism to secure their future.

My place in this place:

I have spent most of my adult life exploring this ground on foot. Most of the time my head is down, watching my step and walking as fast as I can to keep my guide in sight through an endless series of switchbacks, tree roots, and river crossings. You spend hours wet and muddy trying to get to the next camp before sundown. It once took me 13 hours to cover 11 miles.

When I first arrived in 1988, nobody used money. I paid my informants in matches and salt. Every family had a bone knife. I had to carry in all my supplies and trade goods, so each field trip looked like the line of porters you used to see in Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan movies.

During my fieldwork the Hewa have taught me to live in the bush and to identify the birds. They have unraveled the web of pollination and seed dispersal that connects these forests. Over the years these people have patiently explained to me the intricacies of their lives.

Most importantly the Hewa have taught me all the lessons essential to affecting social change — lessons that you can’t learn in school. Through them, and their desire to achieve a consensus, I have gained the patience to listen. I have learned that I need everybody to understand what we are trying to achieve through a protected area before we can move forward. I have learned the patience to sit through endless meetings. I now understand that in a society with no formal leadership positions, it’s important that everyone has the opportunity to voice an opinion, to air a grievance — to feel like they matter. I have learned that ideas and abilities can win the day — if you have the persistence to see things through.

This landscape has shaped my life. The children of the families that first took me in back in 1988 are now my partners in a globally significant conservation project. Not bad for a kid from a mill town in Ohio.

What this place needs:

The Headwaters of the Strickland River need formal recognition as a Conservation Area by the government of Papua New Guinea and a consistent source of funding for to give the landowners a sustainable source of income. These forests are undoubtedly globally important for carbon sequestration, biodiversity, and watershed protection. By establishing the Headwaters of the Strickland Conservation Area, PNG will not only bring international recognition to the Headwaters but also underscore their commitment to conserving their cultural and natural heritage.

Lessons from the fight:

We believe that there are several lessons to be learned here. First, traditional environmental knowledge is a viable tool for conservation. The key is understanding human activity as a source of disturbance that at proper scale can actually enhance biodiversity, but when unchecked is incompatible with a biodiverse landscape. Since traditional environmental knowledge is accumulated over generations, it is, in a sense, the product of a 1,000-year study by generations of Indigenous naturalists. It contains the responses of various organisms to change and disturbance. Our work is leading to increasingly sophisticated interpretations of how native peoples’ awareness of their environment is encoded, processed, and utilized. With biodiversity disappearing fast, there’s not enough time or funding to bring western scientists to the rescue. Traditional environmental knowledge can fill this gap.

Secondly, the current conservation and funding mechanisms are woefully inadequate for conserving biodiversity in Papua New Guinea and, I suspect, the developing world in general. The political forces are aligned for development. Regardless of the will of the landowners, the political obstacles to conservation can be daunting. Landowners in remote regions like the Headwaters lack the funds, time, education, and stamina to lobby politicians. If they’re lucky enough to move the political process, they must find the funding to attend meetings; partners who can translate and produce documents in another language; and reliable partners within the levels of government necessary for a conservation project. If they’re lucky enough to survive running this gauntlet, they will then be asked to do it all again when they pursue funding. When and if they can find a source of funding, landowners will be asked to meet assessment and monitoring requirements that only make sense in the developed world.

Landscapes like the Headwaters are “unexplored” for a reason — they lack the roads and infrastructure that make travel easy. While they won’t admit it, the funding agency representatives that I’ve met with think I’m exaggerating the difficulties of working in the Headwaters. They’ve never seen a landscape so steep and wracked by earthquakes that no one has dared to attempt to put a road through it. They cannot image a hike where it takes 11 hours to travel 13 miles.

They haven’t seen unexplored New Guinea.

Learn more:

Do you live in or near a threatened habitat or community, or have you worked to study or protect endangered wildlife? You’re invited to share your stories in our ongoing features, Protect This Place and Save This Species.

Previously in The Revelator:

Species Spotlight: To Save the Narrow Sawfish, First We Must Find Them