March keeps barreling forward like a freight train full of vinyl chloride — but hope and spring are both in the air, and they smell like victory.

Welcome to another edition of Links From the Brink, where we gather and dissect (in an ethical manner, not like your high school biology class) the environmental news that might otherwise fall through the cracks.

This month we take a look at giant birds, awful laws, an oceanic win, and … fear.

Seas the Day

International victory of the month: It isn’t official yet, but members of the United Nations have ironed out a decades-in-the-making treaty that would protect biodiversity in the high seas — the mostly lawless stretches of the ocean outside national boundaries. (That’s about two-thirds of the ocean, for those of you counting at home.)

If the U.N. member nations all agree to adopt this treaty — and remember, the United States has still failed to sign on to the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea — it would allow for the creation of large marine protected areas, establish an international organization to address biodiversity issues, and restrict companies from exploiting the genetics of ocean life (say, for pharmaceuticals).

This treaty will do a heck of a lot more than conserve dolphins and sharks (although it will do that too, and that’s important). It will help reduce overfishing, ocean mining and oil extraction. And it will also go a long way toward the goal of protecting 30% of the world’s land and water by 2030 — key to slowing both climate change and the extinction crisis.

We’ll be watching to see which nations sign on to this new treaty — and which ones don’t.

Biophobia Redux

Back in 2020, researcher Masashi Soga warned us about how “biophobia,” the fear of living things and a complete aversion to nature, had become the latest risk to conservation. “I believe that increased biophobia is a major, but invisible, threat to global biodiversity,” he told us. “As the number of children who have biophobia increases, public interest and support for biodiversity conservation will gradually decline.”

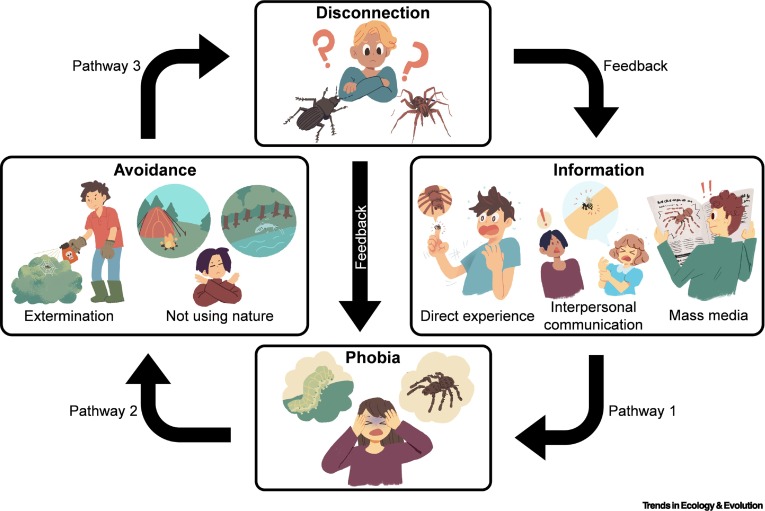

Well, that fear isn’t going anywhere, but luckily neither is Soga, who’s back with another must-read paper titled “The Vicious Cycle of Biophobia.” Here’s a key graphic:

That image, of course, details how biophobia builds into a feedback loop that gets worse at every step.

That image, of course, details how biophobia builds into a feedback loop that gets worse at every step.

But the paper goes beyond that. Much like in their original paper in 2020, Soga and colleagues write that education, outreach and direct experiences with nature can help break the vicious cycle. There’s no “silver bullet,” they caution, but anything we do now to help people appreciate the natural world will help in the long run.

So take a nature-averse friend to a park, ask for help with gardening, or share an article or cute animal video. What have you got to lose — other than the planet?

Gag Off

Best activist news of the month: A federal court has ruled that North Carolina’s infamous ag-gag law, which blocked undercover operations at livestock facilities and other companies, violates the First Amendment. Similar laws have fallen in court rulings around the country. This law was particularly egregious, as it blocked undercover video in any business and made it a civic liability.

But the fight to shine a light on cruel or unsafe agricultural practices ain’t over: Iowa last month asked the courts to reinstate its ag-gag law and introduced a new bill to block drone surveillance of livestock operations. Someone’s got something to hide…

Condor Conundrums

A few years ago I wrote about how livestock owners in Argentina have started using high doses of pesticides to kill Andean condors, a persecution driven by the (needless) fear that the massive birds will attack live sheep and other animals. (Scavengers don’t do that.)

As if those deliberate poisonings weren’t bad enough, now we have reports of two new indirect environmental threats to Andean condors: Pharmaceuticals and plastics.

The first emerging threat, detailed in the journal Biological Conservation, comes again from livestock owners, who researchers found are treating their animals with veterinary drugs — antibiotics and anti-inflammatory NSAIDS — in even the most remote grazing locations. When livestock die on the range, condors scavenge the corpses and get dosed by proxy. The researchers didn’t find this to be a quantifiable danger to Andean condors yet, but they remind us that “these compounds can produce catastrophic consequences for populations of avian scavengers,” like it’s doing for vultures throughout Asia and Africa. Could the same thing happen in South America?

The second threat — plastic — is even more worrying. Researchers tested undigested food regurgitated (gross) by condors at two remote protected sites in Peru and found that almost all of them contained “different sizes and varieties of plastic debris, with a very high frequency of occurrence (85–100%) of microplastics in pellets of both areas studied.” According to the study, published in Environmental Pollution, this means the condors’ prey — mostly camelids and marine mammals — is already packed with plastic, even though the two locations are far from human settlements.

As we’ve seen with whales, eagles and humans, the chemicals from plastic — and their health effects — tend to bioaccumulate and cause the most harm to top-of-the-food-chain predators. Andean condors could soon be added to that list.

Two Contradictory Headlines to Nuke Your Brain

Biden’s DOE Announces $1.2 Billion to Extend or Restart the Life of Nuclear Plants

Nuclear Waste Is Piling Up. Does the US Have a Plan?

Dammed Salmon

Maine’s Milford Dam is supposed to allow 95% of adult Atlantic salmon, an endangered species, to quickly pass through as the fish migrate up the Penobscot River. According to documents obtained by environmental groups and the Penobscot Indian Nation, the dam misses that target by (checks math) 74%.

Yup, only 21% of salmon passed by the dam within the allotted 48 hours. That’s bad.

Milford is operated by Brookfield Renewable Partners, the same company that’s been targeted — and has to date refused — to remove four dams on the Kennebec River. Both the Kennebec and Penobscot rivers, expert say, hold the key to restoring Atlantic salmon.

“Ultimately the fate of the species in the United States really depends upon what happens at a handful of key dams,” John Burrows, executive director of U.S. programs at the Atlantic Salmon Federation, told us last year. If any of those dams don’t allow the fish to pass, he said, “you could basically preclude recovering Atlantic salmon in the United States.”

The salmon’s in your court, Brookfield.

And Finally, in No Particular Order, 10 Stories About Forests

-

- Increasingly Large and Intense Wildfires Hinder Western Forests’ Ability to Regenerate

- Costa Rica Ponders Ways to Sustain Reforestation Success

- California’s ‘Zombie Forests’ Are ‘Cheating Death’ as the Climate Has Changed So Drastically It’s No Longer Able to Support Them

- Why Tropical Forests Are Important for Our Well-Being

- Northern Forests Released a Record Amount of Carbon Dioxide in 2021

- Firewood Theft: The Forests Where Trees Are Going Missing

- How Nepal Regenerated Its Forests

- Saving a Forest of One

- Conservationists Decry Palm Oil Giants’ Exit From HCSA Forest Protection Group

- New Study Finds Gaps in Research on the ‘Wood Wide Web’

That’s it for this edition of Links From the Brink. We’ll be back in late April with another dose of environmental news and analysis.

Until then, stay tuned for the latest on the East Palestine chemical disaster (or whatever train crash comes next), some important news about clean water (what little of it’s left), and more culture war nonsense from the MAGA right.

Also in the weeks ahead: International Day of Action for Rivers (March 14), World Sparrow Day (March 20), Manatee Appreciation Day (March 29) and International Beaver Day (April 7). Check out our full list of environmental holidays for even more reasons to celebrate.

Previously in The Revelator:

Elephant Poop, Tasmanian Snails and Other Links From the Brink