Few people intentionally sail through the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, one of the world’s most notoriously polluted stretches of ocean. Even fewer choose to do so in a ship that’s literally a piece of trash. In fact, only two people have done so: Joel Paschal and Marcus Eriksen. The two men accomplished their 2,600-mile journey in 2008 to help publicize the fact that we need to act now to stop the sea from drowning itself in plastic.

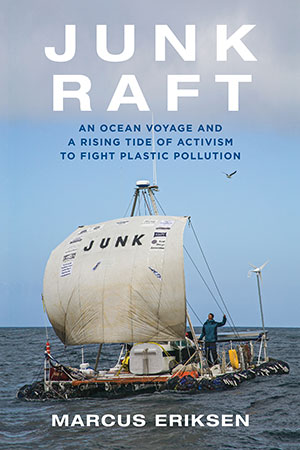

Eriksen, also president and cofounder of ocean conservation organization 5 Gyres, has written a book about his adventure, aptly titled “Junk Raft: An Ocean Voyage and a Rising Tide of Activism to Fight Plastic Pollution” (Beacon Press, $26.95), which came out this week. I recently spoke to him about his new book, his adventure in Junk Raft — and yes, she is a registered oceangoing vessel — and his mission to convince the world to stop using and producing plastic.

Eriksen, also president and cofounder of ocean conservation organization 5 Gyres, has written a book about his adventure, aptly titled “Junk Raft: An Ocean Voyage and a Rising Tide of Activism to Fight Plastic Pollution” (Beacon Press, $26.95), which came out this week. I recently spoke to him about his new book, his adventure in Junk Raft — and yes, she is a registered oceangoing vessel — and his mission to convince the world to stop using and producing plastic.

Cirno: “Junk Raft” recounts your epic trip in a boat of the same name across the Northern Pacific Ocean, from Los Angeles to Hawaii. What inspired you to take this journey?

Eriksen: My inspiration to do it was simply the plastic use and pollution issue. Prior to this, I went sailing on the Mississippi River for five months on a similar plastic-bottle raft. What I witnessed there was a never-ending trail of plastic leading to the sea. And then I went to Midway Atoll and saw all the effects on albatross. My idea for the second raft, Junk Raft, went back to my experience in the Gulf War. I was a Marine on the ground, in a sniper platoon. I saw the region’s great oil rigs catch fire and burn. I couldn’t understand the destruction around me. I wanted to rethink what I was fighting for: Conservation is worth it, not a resource war on petroleum.

I thought, “The plastic problem is fixable. Nonsensically we use plastic to create items we use once or twice and throw away — we just have to stop doing that.”

I have a lot of confidence in how rafts work and perform, and a great team: Joel Paschal, my fellow sailor and adventurer, and Anna Cummins, my wife, who served as a one-woman, land-based support team. All three of us were on a boat with Charles Moore — who coined the term “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” — on his sixth crossing across the North Pacific. This was the start of 5 Gyre’s global research. We’ve done at least 20 research trips since.

Cirno: What kinds of junk was Junk Raft made out of?

Eriksen: 15,000 plastic water bottles donated from schools and recycling centers; 2,000 Nalgene bottles that Patagonia stopped using because they contained toxic BPA; an old airplane cockpit as the ship’s hull, salvaged from wrecks in the desert; and 25 broken sailboat masts as a deck. Everything was lashed together Polynesian-style. We put the plastic bottles in socks underneath the deck, used two masts as an A-frame, and also sewed together spare, damaged sails as our mainsail.

We had modern communications and electronics on the raft — solar panels, wind generator, new batteries, chart plotter, satellite phone, computer. I could plug in the satellite phone to the computer and upload short, half-megabyte videos to the internet for our followers to watch. Anna was our land-based mission control. She was constantly checking weather for us and fundraising like mad to help support our sailing journey on the Junk Raft.

Cirno: How long did the trip take?

Eriksen: It took two months to build the raft and three months to sail it. Our sponsors thought our decision to sail away on that raft was a death wish. But as soon as we were halfway across, people realized we were succeeding — that we were doing it. When we got to Hawaii, a hundred people stood cheering for Joel and me on the dock. We later learned that a million people were following our journey online.

Cirno: In November I sailed the same stretch of the North Pacific that you did, but I was in a proper steel sailboat. What were some of the challenges of sailing in Junk Raft?

Eriksen: For what it was made of, the raft was rather seaworthy…it got the job done. But there were many difficulties, especially during storms.

The boat was constantly falling apart. We had problems with leaks and parts falling off. On day three we had our biggest storm, with 50 mile-per-hour winds. All the bottle caps began spinning off, and as a result, the boat sank a foot into the water. Our deck was submerged and we started sinking. So I called Anna and she sent forth a resupply mission to bring us glue so we could secure the bottle caps. They also brought greens and other fresh foods — because much of our food was damaged by water — and beer.

Cirno: When did you decide to write a book about the journey?

Eriksen: Two-and-a-half years ago, before I lost my memory of the journey and moved on to my next project. I’d kept a journal the whole time we sailed, and the movement to end the plastic problem was growing fast.

Cirno: So what was your goal when writing this book?

Eriksen: I wanted to use adventure as a vehicle to attract a lot of people. Here’s this crazy adventure we had, but here’s this issue we should all be knowledgeable about. We sailed 1.5 miles per hour, our ship began falling apart, we tried to outrun hurricanes, and more. It’s exciting but it teaches a lesson: We’ve created such a huge plastic trash problem that it’s become easier to sail across the ocean in a raft made of trash than to clean it all up.

Cirno: This journey was in 2008; it’s now 2017. How do you feel about the progress we’ve made on these issues?

Eriksen: I think it’s been highly positive. We’ve accomplished a lot. There’s been a huge surge in environmental NGOs forming to try to address the problem in a variety of ways, and some are doing great things, helping establish legislation that curbs or bans plastic use or changes peoples’ habits so that they use less plastic.

Yet stakeholders have reached this impasse: Many people are aware the problem exists, but we as a global community are not doing enough to make sure it doesn’t get worse.

What we need now is a revolution by design. There are some plastic products that really have to go, such as wrappers on foods and products. Right now we need to scale back plastic production immediately and eventually stop it. We need better waste management and recycling programs. We need to make bioplastics mainstream and affordable. We must do more recycling. Basically, we must do things that don’t harm people and the planet. Plastic has got to go.

© 2017 Erica Cirino. All rights reserved.

Previously on The Revelator:

Clever stunt! And required some real know-how and grit. Political theater can be effective in making a point. https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/acb2e1cde8b16c176f007d6174960cffef59ed6a3d9041e2ecfa9895bedd6e18.jpg These two high school students dressed in plastic bags to make their point to the San Luis Obispo County Commissioners to approve a plastic bag ban.

Plastic is made from petroleum. (It can also be made from plants, such as biodegradable garbage bags or dishware, but this form of plastic is not causing the problem.) Oil is extremely destructive once it’s extracted, and it needs to be left under the land and the water where it belongs.