How do you get people to care about something they can’t see?

That has always presented a challenge in environmental conservation messaging, where a consumer’s decisions can affect people or species on the other side of the planet. It can be hard to connect the dots between a candy bar containing palm oil sold in Indiana to the destruction of an orangutan’s habitat in Indonesia, or how purchasing a cheeseburger in Nebraska contributes to deforestation of the Amazon.

While advocates have had some notable successes communicating these threats, promoting similar efforts to protect ocean life has proven even harder — even for communities that live right next to those waters.

“For many people in the public, thinking about what lives in marine environments is a foreign concept,” says Nina Wootton, a marine researcher at the University of Adelaide. “Unless you’re a fisher or you love to SCUBA dive, the chance of you ever seeing the marine environment is low, especially for offshore areas. The benefits of protecting the ocean … are unknown and unseen to many people.”

A new study hopes to turn that around.

The (Hidden) Value of MPAs

Two of the biggest threats to marine biodiversity come from unsustainable overfishing and habitat loss — both of which also threaten the food security and livelihoods of coastal communities.

To fight these threats, governments have increasingly turned to creating marine protected areas (MPAs), essentially underwater national parks that protect habitats and organisms that live within them.

Well-designed and well-implemented MPAs have more fish, bigger fish, and more species of fish than in similar unprotected areas, allowing recovery of once-overfished species and benefitting surrounding waters. Recovered species don’t stay in MPAs — they expand their habitats through what is known as the “spillover effect.”

But misunderstandings about the goals of MPAs, and a sometimes top-down heavy-handed approach to implementing them, can make no-fishing zones a tough sell in coastal communities which depend on fishing. This, in turn, can reduce an MPA’s effectiveness, or make it impossible to establish them in the first place.

What can we do to build local support for MPAs and enhance their success? Wootton and her colleagues tried using an innovative collection of virtual and visual tools to persuade people of the benefits of an MPA. It focused on beloved marine species that would be protected by an MPA network, which the researchers called the “Fab Five.”

A study about their efforts was published this March in the journal Biological Conservation.

The Fab Five

As previous work has shown, persuading people of the need to protect the environment is complex and difficult, and simply presenting a dry and technical list of facts doesn’t do the trick. Generating public support for the implementation of marine protected areas is vitally important to their success.

“In the end it’s mostly community members who use those MPAs, so it is essential that everyone is on board,” says Wootton. “Many coastal communities rely on marine resources, such as fishing and marine tourism, for their livelihoods, and implementing an MPA without community input leads to conflict and potential economic losses. But when we engage with the community during the MPA planning process, it can help address concerns and mitigate negative economic impacts.”

Past efforts to generate community buy-in for new protected areas have shown that the process is complex, time-consuming, and can meet with mixed results. The communities’ costs from limiting fishing are clear and immediate, while the benefits are uncertain. And for people who don’t depend directly on fishing for their livelihoods, it can be hard to get them to think about marine biodiversity at all.

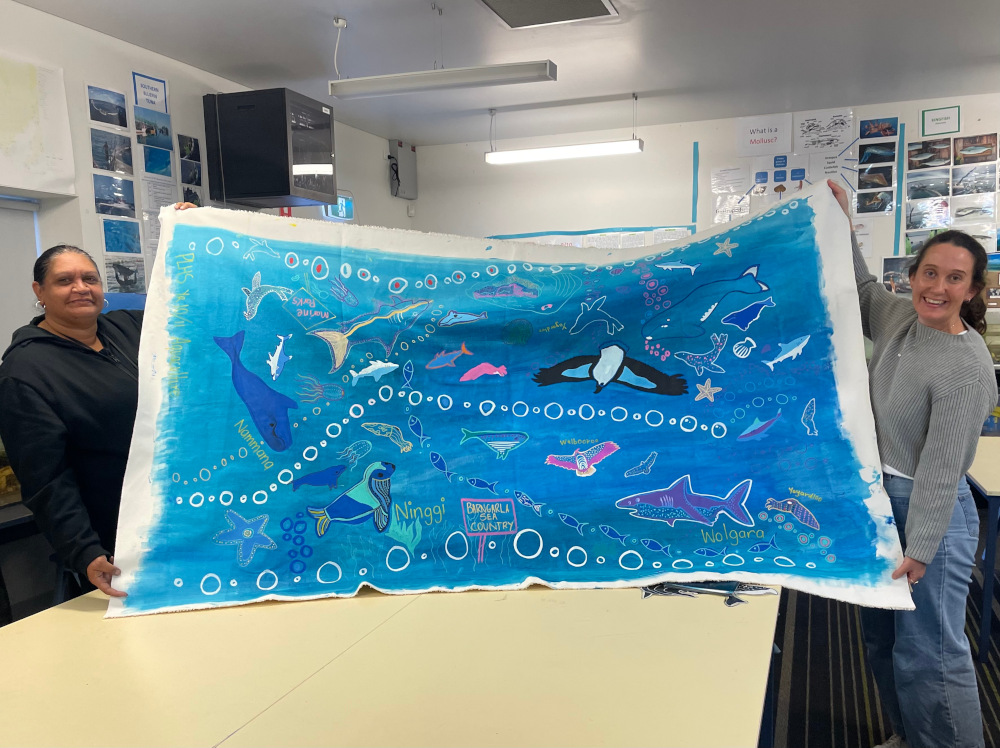

Wootton and a team of marine scientists, in partnership with First Nations Sea Country peoples, wanted to assess what gets community members to care about the ocean and support an MPA. Working in South Australia, which has 26 commonwealth or state marine parks, they picked five iconic local species who benefit from the MPA, including the Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea), giant Australian cuttlefish (Sepia apama), white-bellied sea eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster), great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), and southern right whale (Eubalaena australis).

With these charismatic but varied species in hand, they then engaged in a large outreach project involving virtual tools and artwork featuring those animals.

And it worked. The authors report that the visually engaging narrative created by their “Fab Five” tools not only got people engaged in the discussion, but they contained to engage over time. Schools held “Fab Five” art contests, community festivals featured “Fab Five” mascots, and museums planned exhibits around the animals. Volunteers at each event handed out educational materials directing people to learn more about the MPA.

This had a collective effect, too. Media coverage of the South Australia MPAs and associated issues dramatically increased, spreading once-low background awareness far and wide.

Marketing for a Good Cause

“The Fab Five is based on the big 5 safari animals from Africa,” Wootton says, referring to the most famous and beloved species that people want to see (and originally wanted to hunt) when visiting Africa. “By choosing five charismatic animals that are particularly important to South Australia, we were able to get the public to form a connection with the marine environment, which helped in guided a deeper understanding of what MPAs do and why they’re good.”

The use of these “Fab Five” beloved Australian marine animals was an example of conservation marketing.

“Conservation marketing is leveraging the same tools and techniques that businesses use to sell us products, but for social good like the conservation of biodiversity,” says Diogo Verissimo, a research fellow at the University of Oxford who was not involved with this study. “Threats to biodiversity come from things people do, and stopping or mitigating these threats means we need to get people to think or act a little bit differently. Marketing tools are great for that.”

And while Verissimo suggests taking a step back and doing some initial marketing research to see which species would be most effective at generating public support for an MPA, he was pleased with some of the selections.

“Anyone who is involved in conservation tends to assume that a given species is beloved by all, but even with really popular animals there will be people who dislike them, so it’s very important to understand local cultural and social contexts when using featured animals,” he says. “Whales and seals are used very widely as featured animals, but species like sharks are more polarizing, with some people who love them and some people who really dislike them. And it was really nice to see a cuttlefish featured, because not many invertebrates make the cut in conservation marketing.”

Check out our recent paper on engaging communities with marine parks. We used the ‘Fab 5’ to help students connect with all the wonders of the ocean. Read the paper here: https://t.co/VSCDwIisXM 🦈🐙🦭🐳🦅 #MPA #Scicomm #SciArt pic.twitter.com/8w561W7rAU

— Nina Wootton (@DrNinaMarina) March 18, 2024

Strikingly, this new paper reports that traditional community advisory panels, often used to establish a formal place for community input on a proposed MPA, did not work here — people didn’t even show up to have the conversation. And surprisingly, despite the importance of coastal resources to local communities, many of the people her team spoke with had no opinion about the MPA because they had never heard of it.

This failure of traditional outreach makes the success of the Fab Five campaign even more valuable.

“We found that visual engagement, including the use of artwork, helped significantly in getting the public to connect with the marine environment,” Wootton says.

With this success in South Australia, Wootton says she believes that the Fab Five model could easily be adapted to other locations, focusing on species found there.

“I suggest trying to include a range of animals, some of which are well known and some of which are not, so you can get people interested while also teaching them something new,” she says. “And try to pick a few species that are a little bit whacky and weird. It makes it more fun!”

Get more from The Revelator. Subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Facebook and X.