A version of this essay was originally published at Counterpunch. Fire moves rapidly, so this version has been updated and expanded.

Both Congress and the U.S. Forest Service have told us that our forests and communities are experiencing a “wildfire crisis” — that an increasing amount of wildfire is burning on our landscapes and fire severity is increasing. The primary “solution” they’re currently planning and implementing, embodied in the Wildfire Crisis Strategy, is a substantial increase in logging, thinning and burning treatments in our forests, for which Congress has provided billions of dollars of funding, along with the mandate to get it done.

So that begs the question — to what extent are we actually in a wildfire crisis? Certainly the aggressive and environmentally damaging logging and over-burning being carried out in some forests, with much more to come, should be based on solid data and science.

As someone who’s worked to protect western forests for over 15 years as an advocate and journalist, including as the cofounder and director of The Forest Advocate, I’m searching for answers to fundamental questions underlying prevailing forest-management paradigms and strategies.

The basic premise of the Wildfire Crisis Strategy is that wildfire is greatly increasing on our western landscapes. The facts on that shouldn’t be difficult to obtain, as the Forest Service and other land-management agencies maintain records and maps of wildfire perimeters. This data goes into national wildfire databases, such as one called Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity. MTBS is “an interagency program to map the location, extent and associated burn severity of all large fires (including wildfire, wildland fire use and prescribed fire) in the United States across all ownerships from 1984 to present.” This program is largely run by the U.S. Geological Survey and the Forest Service, and datasets include state and federal fire history records.

However, Forest Service wildfire perimeter data is vastly compromised: A large proportion of acres burned within the officially designated wildfire perimeters are actually ignited for supposed “resource benefit objectives” by the Forest Service itself, most often by aerial ignitions via drones and helicopters. In many cases the majority of a fire that is called a “wildfire” on national forest lands is actually Forest Service intentional burning. This strategy for managing fire has increased to the point that numerous fires are substantially expanded by intentional burning.

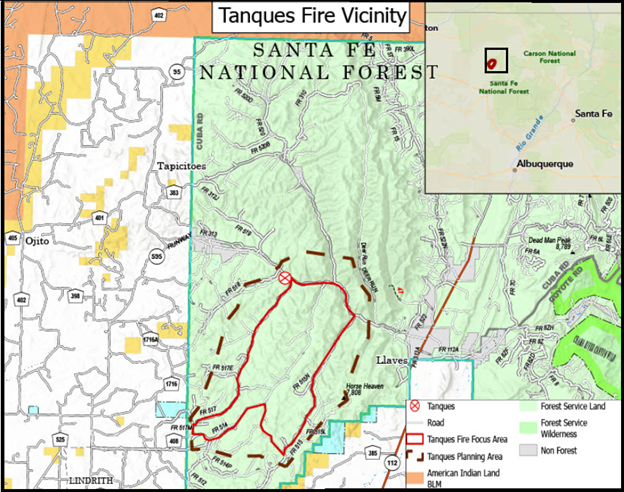

The recent Tanques Fire in the Santa Fe National Forest was originally ignited by a lightning strike and then greatly expanded through aerial and ground firing operations under command of the Forest Service. According to a Forest Service news release, the fire was first reported on July 18 and by July 25 had grown to only 13 acres.

But by that date, the Forest Service had made the decision to expand the fire up to a “planned perimeter” of 7,000 acres with firing operations. That means the Service intended to expand it up to 538 times its size. The fire may have continued to slowly expand naturally, but relatively high vegetation moisture from recent rains made it unlikely that the fire would spread much on its own. By Aug. 1, when the fire had been expanded to 6,500 acres, enough rain came that it was apparently too difficult to expand the fire any further. It’s hard to say exactly which part of the 6,500-acre “wildfire” was due to intentional burning and which was “natural” wildfire, but it is clear the vast majority of the acres burned were due to the Forest Service’s own ignitions. Nonetheless the agency calls the Tanques Fire a wildfire.

Recently the Forest Service and The Nature Conservancy (an organization closely aligned with the Forest Service), along with a university professor, authored the “Tamm review: A meta-analysis of thinning, prescribed fire, and wildfire effects on subsequent wildfire severity in conifer dominated forests of the Western US.” This review is a consideration of the efficacy of forest “thinning” and prescribed fire in moderating the incidence and severity of wildfire. It begins with citing a 2022 research article to support their contention that “In the western United States, area burned [by wildfire] has doubled in recent decades.”

That 2022 study, conducted by Virginia Iglesias and other researchers at the University of Colorado, found that “U.S. fires became larger, more frequent, and more widespread in the 2000s.” Their conclusion is based on data from over 28,000 fires in the MTBS dataset. However, since this dataset is derived largely from Forest Service wildfire data, it includes the large proportion of fire intentionally set by the Forest Service during wildfire-management operations. The agency does not differentiate in its published wildfire data between fire ignited during wildfire-management operations and fire that burned due to the original wildfire ignition. The study concludes that there have been more fires and larger fires in the West since 1999 — yet we have no way of knowing to what extent this is true, given that the Forest Service has, over the past 20-25 years, been igniting more and more fire under the umbrella of wildfire management and calling it all wildfire.

The first publicized example of such wildfire expansion was the 2002 Biscuit Fire. Timothy Ingalsbee of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology estimated that a large proportion of the Biscuit Fire was ignited by Forest Service firing operations. Inglasbee stated in a 2006 report largely focused on the Biscuit Fire that “burnout operations can sometimes take place several miles away from the edge of a wildfire, or alternately, miles away from the fire containment line.” Wildfire expansions have greatly increased since 2002, and wildfire starts, such as lightning strike ignitions, are often simply the “match that lit the fire,” leading to numerous firing operation ignitions to implement intentional burns that the agency calls wildfires.

The Tamm Review “found overwhelming evidence that mechanical thinning with prescribed burning, mechanical thinning with pile burning, and prescribed burning only, are effective at reducing subsequent wildfire severity.” These conclusions are controversial and do not consider research from independent scientists. In 2022 independent conservation scientists published a paper summarizing a growing conservation perspective and strategy, “Have western USA fire suppression and megafire active management approaches become a contemporary Sisyphus?” Based on their collective research, the authors “urge land managers and decision makers to address the root cause of recent fire increases by reducing greenhouse gas emissions across all sectors, reforming industrial forestry and fire suppression practices, protecting carbon stores in large trees and recently burned forests, working with wildfire for ecosystem benefits using minimum suppression tactics when fire is not threatening towns, and surgical application of thinning and prescribed fire nearest homes.”

However, an even more fundamental issue with the Tamm Review is that the purpose and need for such aggressive forest treatments are at least partially predicated on flawed data that indicates wildfire has doubled on our landscapes in recent decades. The acreage burned by wildfire is likely increasing given the warming and drying climate and the abundance of fuels, but who knows to what extent, since the wildfire data is so skewed by the inclusion of the Forest Service intentional burns. This data issue also affects considerations of trends in fire severity, and that should be investigated.

A significant proportion of wildfire research depends on wildfire perimeter data, including the University of Colorado research referenced as support for the premise of the Tamm Review. It is clear we have little knowledge of how much fire that was not ignited by the Forest Service has burned on our landscape in recent decades. It’s a major flaw in “wildfire” data. No forest management actions should be contemplated or initiated based on such data.

Yet Congress and the Forest Service are going forward with a strategy for addressing the “wildfire crisis” without having determined with reasonable data and responsible science to what extent the crisis exists. That’s unacceptable — especially considering that the remedy often involves severely damaging impacts to our forests and communities. Clear parameters need to be developed for how to support appropriate amounts of fire on our landscapes, based on accurate data and a range of scientific research. Any resulting plan should be analyzed with an environmental impact statement.

There is understandable concern about wildfires increasingly impacting wildland/urban interface communities, and this issue requires serious consideration and action. However, evidence clearly shows that burning of homes and communities by wildfire is not significantly impacted by logging, thinning, and intentional burning treatments out in the forest, and that only the 100 feet surrounding homes and other structures is relevant to structure ignitions.

The best response to the home ignition problem is home hardening and treating the landscape immediately surrounding homes and other values. This takes a coordinated effort between governmental bodies, land-management agencies, and the public. Such coordination would more likely occur with increased transparency on the part of the Forest Service and affiliated scientists, which could build trust with the public.

The accurate collection and categorization of wildfire data, which underlies research concerning wildfire, are a fundamental basis for transparency and trust — and good science.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

Previously in The Revelator:

How Do We Solve Our Wildfire Challenges?