As human industry belches out more carbon dioxide, the chemistry of our oceans is changing. The resulting acidification is endangering coral reefs and the myriad creatures that depend on them. Science writer and one-time ocean researcher Juli Berwald wondered how ocean acidification affects jellyfish. Will they be climate change winners or losers?

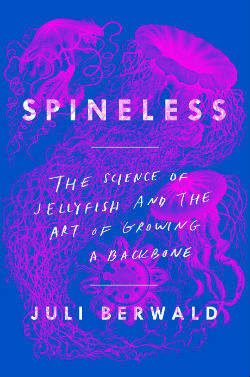

The answer, she learned, isn’t simple — scientists don’t even agree on whether jellyfish populations are increasing or decreasing. But her question offers a jumping off point into the deep blue. The result is Spineless: The Science of Jellyfish and the Act of Growing a Backbone, a book that’s both a scientific journey and a personal one.

Jellyfish are beautiful and ethereal looking, but they don’t have the easy charisma of some marine animals. They’re not dolphins or clownfish or even octopuses. Most of us would rather not get close enough to touch them. Yet thanks to Berwald’s years of research, global treks and accessible language, Spineless is an enchanting read.

Scientists still have much to learn about jellies, but what we already know is fascinating enough. It turns out jellyfish have traveled to space, are informing robotics research — and are delicious in salad (if you know the secret to their preparation). And they can tell us volumes about the ocean they live in.

“Understanding jellyfish means recognizing the oceans in their complexity rather than homogenizing their problems,” she writes in the book.

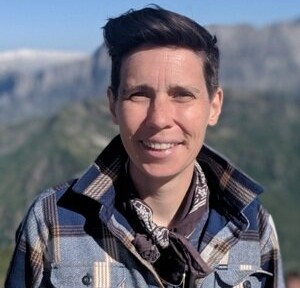

We wanted to know more about jellies, so we asked Berwald about her process of discovery, what scientists are learning about jellyfish and how they can help us better understand the ocean’s biggest challenges.

Your book is a scientific journey and a personal one. What was your favorite part of the process?

When I discovered jellyfish, I was an ex-oceanographer-turned-soccer mom living in Austin, Texas. I had become complacent writing textbooks but didn’t quite have the insight to realize I was craving something more. Jellyfish became a kind of secret obsession that took me back to the sea in my mind, even if I was still physically in a landlocked home office overrun with kids’ toys. As I became more fascinated with their biology and ecology, jellyfish gave me the confidence to discover their larger story, and mine too.

Since you first began studying jellyfish, what have you seen change about our scientific understanding of them?

The recognition that jellyfish aren’t a dead end to the food chain is a big deal. For decades, scientists thought of jellyfish as wasted energy largely because the best tool we had for studying what-ate-what was looking inside predators’ bellies. When you do that, you rarely find a jellyfish. But with new molecular tools we’ve discovered that loads of animals eat jellyfish — including top predators like penguins and tuna. It looks like jellyfish are at the very least an important food when supplies run short and maybe even critical to the food web.

As you write in your book, there are a number of things that make jellyfish unpopular — from stinging swimmers to clogging power plants. What are some things we should appreciate about them?

Jellyfish are a cornucopia of superlatives. The smallest animal in the world is a parasitic jellyfish called Polypodium. The colonial jellyfish, Praya dubya, grows to 120 feet, rivaling the blue whale’s length. The oldest muscle discovered is 540 million years old; it came from a jellyfish. And here’s a whopper: That stinging cell, it explodes out of its capsule with an acceleration 5 million times the acceleration of gravity. It’s the fastest known motion in the animal kingdom.

Also, jellyfish are the most efficient swimmers in the sea. And they aren’t out there just bumbling around. They have many little faces around the edge of their bell called rhopalia that they use to sense the world. Each one has eyespots, a sensory region like a nose, a balance organ like our inner ear and connects to a pacemaker like our heart. And that doesn’t even leave space to talk about their incredible glowing or their insane regenerative capabilities.

How can jellyfish help us better understand the crises facing the ocean?

Jellyfish have adaptations that allow them to do well in today’s damaged seas. They are both eaten by fish and compete for food with fish. So overfishing decreases their predators and increases their prey. They have a very important sessile stage called a polyp that lives on the underside of hard surfaces. Construction of docks, jetties and oil rigs provide a lot more coastal habitat for those polyps.

Because of their jelly insides, they can withstand low-oxygen environments better than more cellular animals with higher metabolism. Those dead zones are expanding because of pollution. And shipping and the proliferation of larger canals provides pathways for jellyfish to become invasive species. Jellyfish populations do ebb and flow naturally. But in places where jellyfish are chronic, it’s often a signal of a compromised ecosystem.

You wrote that funding in 2013 for space exploration outpaced ocean exploration 150 to 1. How do you think we can begin to close that gap and get more people interested in the fate of our oceans?

Ocean scientists have been trying to figure that out for a long time. It’s not that the ocean isn’t inspiring enough. It is. The problem might be exposure. Everyone can look up and wonder about space every day, but only if you live on the coast do you see the ocean every day.

The best answer I have is that we need more diverse voices telling stories that resonate in ways people can’t ignore. I personally don’t watch very many ocean documentaries because I get tired of somber male voices. (No offense, David Attenborough.)

Many books about marine science have that same problem. I used to finish them — often 10 chapters told in an authoritarian voice — and think, there’s no way I could write a book like that. Then I changed the inflection and I thought, but I could write a book like this. This being a book about my own journey to grow a spine as much as about the science of jellyfish and what these incredible creatures mean for our planet’s future.

![]()