Can you imagine an ocean without sharks? That’s a distinct possibility in some parts of the world, as new research reveals that one third of chondrichthyan fish species — that’s sharks, skates, rays and chimeras — are now threatened with extinction.

Sharks and their relatives face a lot of threats around the world, including the destruction of coastal ecosystems and pollution. But the research finds that one danger eclipses all the others: overfishing.

And that, in turn, speaks to a bigger problem: It’s not just sharks. We’re rapidly emptying the oceans of marine life around the globe, which experts say could lead to ecological collapse in the water and starvation for humans on land.

“Problems with sharks and rays forewarn of coming problems,” says Nick Dulvy, a professor at Simon Fraser University and lead author of the new study.

Dulvy says this research examines the problem through the lens of sharks and rays, but it “may be the most complete picture of the effects of fishing on the world’s oceans.”

Now that we understand the scope of the overfishing problem, what can we do about it — while there’s still time to save many of these species from extinction?

Start With the Science

“Overfishing can, and must, be tackled through the implementation of science-based catch limits, bycatch mitigation and behavior change,” says Ali Hood, the director of conservation at the Shark Trust.

We know this works. Science-based catch limits have been effectively established for around 10% of shark fisheries around the world, including most of the shark fisheries in the United States, and many currently unsustainable fisheries could be made more sustainable with relatively modest changes to management. Mitigation techniques such as fishing gear changes have helped reduce bycatch. Seasonal area closures and marine protected areas, when put in the right place, can play a huge role.

Fisheries for some species can be made more sustainable, but other species are so far gone that more extreme measures are needed.

“Vulnerable or near threatened species can be brought into sustainability through better fisheries management, but some species are so sensitive that strict limits on catch are needed,” Dulvy says.

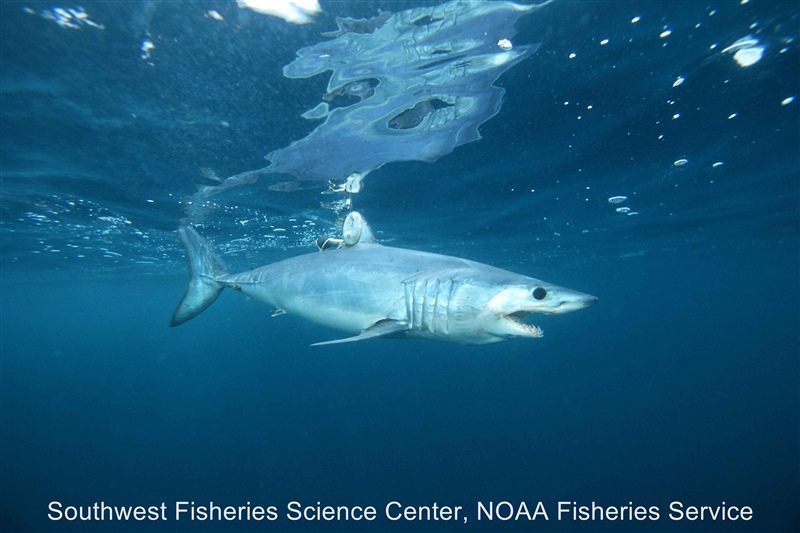

Case in point: the shortfin mako shark, commonly caught as bycatch in Atlantic tuna and swordfish fisheries and experiencing catastrophic population declines.

“Perhaps the world’s clearest case for urgent conservation action is the North Atlantic shortfin mako,” says Sonja Fordham, the president of Shark Advocates International and a coauthor on the new study. “The advice from International Commission for Conservation of Atlantic Tunas scientists has been clear since 2017. A dramatic reduction in fishing pressure is urgently needed to reverse decline and the first basic step is a complete prohibition on retention.”

The ICCAT finally listened to its own scientists in late November, when it agreed to ban fishers in the North Atlantic from landing any shortfin mako sharks, even accidentally. The move effectively bans any fishing for this heavily exploited species. While conservationists like Fordham celebrate the move, they also caution that the retention ban is temporary and in its current form won’t last long enough to allow makos to fully recover.

Engage Communities and the Public

Many experts say the way to solve overfishing is to work with the communities living near sharks to come up with solutions. Top-down solutions that don’t incorporate a region’s needs and voices are less likely to be followed by locals. For example, pressure from international environmental groups to reduce shark fishing led to the collapse of some fishing communities in Indonesia, which resulted in former fishermen turning to activities like human trafficking and drug and weapons smuggling to pay their bills.

In contrast, a model pioneered by the Shark Reef Marine Protected Area in Fiji takes revenue from international SCUBA tourists and pays former fishermen to not fish.

Public-awareness campaigns and initiatives can also generate support for sharks, influence consumer behavior, and even inspire legislative action.

“Concerned citizens are key to reversing shark and ray declines and can help a lot by just letting policymakers know that they support conservation efforts,” says Fordham. “They help build the political will necessary to ensure government commitments are followed up with concrete actions, such as limits on fishing. Whether it’s contacting policymakers and news editors or celebrating species through social media and art, everyone can help. Vocal public support for shark and ray conservation is not only meaningful. It’s essential for a brighter future.”

In the most recent example of this citizen engagement, public pressure persuaded the Canadian government to switch their position and support last month’s ban on retaining mako sharks in Atlantic fisheries.

Expand the Concept of ‘Sharks’

Although public support has certainly helped some shark species, the same can’t be said for lesser-known shark relatives like the sawfishes and guitarfishes.

“We need the public to not only broaden their concept of a ‘shark’ but also care enough to speak up on rays’ behalf,” says Fordham. “Rays are generally more threatened and much less protected than sharks, and the reasons why we worry about shark overfishing apply to rays as well.”

View this post on Instagram

Fordham uses social media conversations like #FlatSharkFriday and #ElevateTheSkate to try to get members of the public to learn about and care about skates and rays (lovingly termed “the flat sharks”) as much as they care about sharks. She points out that the public is increasingly aware of especially famous species like manta rays and sawfishes, but lots of skate and rays (including “rhino rays”) still need our help.

Don’t Look for Silver Bullet Solutions

While the shark conservation crisis is often associated with demand in China for shark fin soup and some charismatic species like makos, it’s truly a global problem that can’t be solved easily.

“Almost every costal nation in the world catches sharks and rays, including many species now threatened with extinction, and all have a role to play in preventing the impending mass extinction,” says Luke Warwick, director of shark and ray conservation for the Wildlife Conservation Society, who was not involved in this study.

Although some conservation groups advocate for simply banning all shark fishing to address the crisis, experience shows that the issues are much more complicated.

“The reality is that in many nations, sharks and their relatives play important roles in food security and livelihoods, and as a result, simply banning fishing will lead to significant social and economic problems,” says Colin Simpfendorfer, an adjunct professor of marine biology at James Cook University and a coauthor on the new study. “We need to ensure that communities that rely on sharks and rays can continue to do so.”

Simpfendorfer notes that this doesn’t mean that unsustainable overfishing must be allowed to continue, but that cutting off a vital food supply cold turkey is not the best solution.

Dulvy agrees. “Shutting down all shark fisheries means a billion-dollar hole in coastal economies, and a food security crisis,” he says.

Something Must Be Done

Unfortunately, in a pattern familiar to environmentalists, governments have made many great-sounding shark conservation commitments over the years and haven’t always followed through.

“These alarming population declines are the results of decades of indifference by many governments,” says Hood. “This situation is avoidable, and we need to move shark conservation beyond rhetoric and address reality. Will governments now listen to the calls of the shark conservation community and take concerted action?”

This crisis demands a response, in the form of more and stronger conservation policies tailored to each specific situation. Failure to act could have terrible ecological consequences for the ocean and the humans who depend on it.

“Without decisive action to reduce the take of sharks and rays in fisheries, the extinction crisis will worsen, and more species will go extinct,” Simpfendorfer says.

Author’s note: David Shiffman is a former postdoctoral research fellow in the Dulvy lab at Simon Fraser University, and a current senior research advisor to the IUCN Red List’s Tuna and Billfish Specialist Group. He has never worked directly on IUCN Red List Shark Specialist Group research projects.

![]()

Previously in The Revelator:

Behind the Science: How Do We Know How Many Shark Species Are at Risk?