Just over 100 years ago — on Feb. 1, 1917 — Katherine Schaub reported for the first day of her new job at Radium Luminous Materials Corporation in Newark, New Jersey, not knowing the job would eventually kill her.

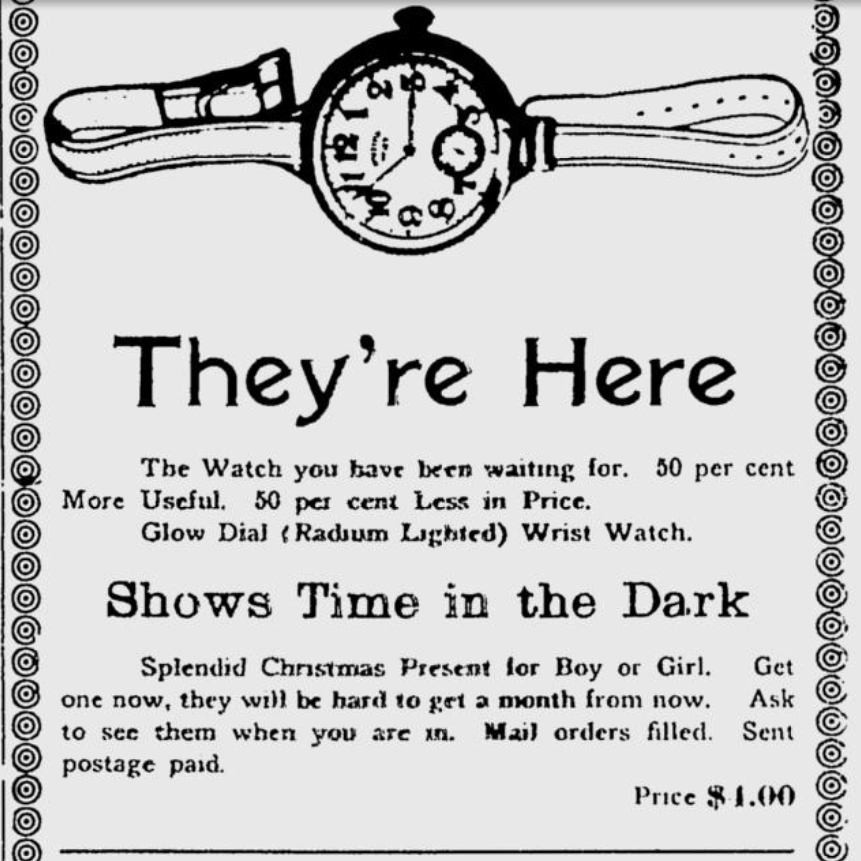

Schaub, and hundreds of other young women just like her, found themselves employed thanks to the radium craze of the early decades of the 20th century. In the Newark factory, and others like it, women hunched over trays full of wristwatches, upon which they meticulously painted glow-in-the-dark numbers with a proprietary concoction containing something they were told was perfectly safe: radium.

Discovered less than two decades earlier, radium was considered something of a wonder material at the time, used on everything from toothpaste to furniture cleaner to purported medicines.

The watches, though, were something less trivial, intended for soldiers fighting in World War I. Thousands of them shipped from the Newark factory. To produce the watches, the girls would put fine-haired paintbrushes into their mouths to form a precise tip and then dip them into the radium paint, a process they repeated for hours on end.

At the end of each day, the girls — their clothes and hair covered in tiny bits of radium dust — would walk home, glowing in the dark. The neighborhood called them the “ghost girls.”

In reality, they were the walking dead.

Years later the pain began to set in. The radium had settled into their bones and flesh, causing debilitating exhaustion, rotting necrosis and crippling bone fractures. But even as the women’s jaws and other bones began to decay, their doctors were at a loss as to why. The health risks of what later came to be known as radium poisoning had not yet made their way into the medial literature. So the women suffered as their bodies failed, and no one could tell them why.

The watch companies, however, had begun to understand what their wonder substance actually did to the human body. Rather than admit their mistake, they continued production and made every effort to hide any hint of their wrongdoing.

The truth eventually leaked out, but it was too late to save anyone. As the women’s bodies, in essence, rotted away, and as they died one by one, they struggled in court and in the press for any form of justice they could find.

Few found that justice, but those who did changed the world.

British author Kate Moore, who first encountered the Radium Girls while directing a play about them, now recounts their story in her meticulously researched new history book, “The Radium Girls” (Sourcebooks, $26.99). It’s a powerful, emotional and haunting volume — part medical mystery, part legal thriller, part horror story — that brings the women and their struggle to life in a way that eclipses previous articles, plays and documentaries.

British author Kate Moore, who first encountered the Radium Girls while directing a play about them, now recounts their story in her meticulously researched new history book, “The Radium Girls” (Sourcebooks, $26.99). It’s a powerful, emotional and haunting volume — part medical mystery, part legal thriller, part horror story — that brings the women and their struggle to life in a way that eclipses previous articles, plays and documentaries.

“That that was my driving force,” Moore says, calling on Skype from her home in London. “I wanted the women to be real. I don’t think you can understand the tragedy unless you know who it is that’s been affected.”

To research her book, Moore unearthed reams of letters from the women, along with documentation from their health and court cases. She also tracked down surviving relatives who recalled the Radium Girls and shared their heartrending stories.

“A lot of the people I interviewed were in their late 80s or 90s,” Moore says, noting that some of the family stories might have been lost to time had she waited longer. The most moving of these interviews, she says, was with the great-niece of a Radium Girl named Catherine Donohue. “One of the questions I asked her was, do you remember Catherine crying out with the pain? Because I was trying to picture the scene of the sickbed and that sort of thing, and her response was that she didn’t have the energy to cry out. She would just moan.” She pauses. “That for me was really haunting.”

Unearthing the radium companies’ documents also gave Moore disturbing moments. “It’s not necessarily a new thing, but it was shocking reading,” she says, a hint of anger in her voice. “Just realizing they knew. There’s no two ways about it, it was a total cover-up. That was shocking to see that they knew they were killing these girls and it, you know, just didn’t mean anything.”

But from the horror of their decaying bodies came resolve. The Radium Girls, as they came to be known in the press, stood up for their rights, fought for themselves in court, and helped to create laws that would later protect millions of people.

“As I talk about in the book, it seems bizarre in a way that poisoning wasn’t originally listed as something that your employer could do to you,” Moore says. “It was the Radium Girls that got that put into the statutes. And then building from there, this was one of the first cases where employers were held liable.” Thanks to these women’s quest for justice, industrial employees in the United States have the right to know if they’re working with dangerous chemicals and to know the results of any company-sponsored medical tests. “They can’t conceal the results in the way that happened to the Radium Girls,” Moore says. “All of those are things that built from this case.”

Some of the protections took decades to materialize, but Moore says the ghost girls helped to pave the way. “It’s cases like the Radium Girls that have that kind of pressure that adds until something gets done,” she says.

Of course, that also makes the book — and the decades-old events it recounts — fiercely relevant today. “Hopefully Donald Trump won’t revoke all of those protections,” Moore says. “We were in the States at the end of January and talking to independent booksellers about the book, and they said how timely it is. People talk about bureaucracy and red tape and how it stops businesses from being able to be profitable, but a story like this actually reminds us that there’s a reason that red tape is there. We joke these days about health and safety laws, but actually they’re there for a very important reason — so that companies don’t put profits before people. They are supposed to be held to account if there is something dangerous they are getting employees to do.”

She adds that the book puts a human face on the need for worker-protection laws. “These laws that we now are supposed to abide by, they have human stories and faces behind them. They’re not just there for red tape, they’re there for a reason because other people have lost their lives.” (The Trump administration has already taken several actions that could increase worker exposure to toxins and reduce ability to track occupational injuries and illnesses.)

It’s also a reminder that the effects of little-understood toxins can take a long time to materialize — many of the Radium Girls worked for years before they got sick — and last for decades. While researching the book, Moore visited Ottawa, Illinois, the home of one of the radium companies, which is still an actively contaminated Superfund site. “That was the crazy thing about radium being used anyway, you know,” she says, incredulously. “It’s got a half-life of 1,600 years. Even though it was used on throwaway products and it was a kind of fun thing, it had this devastating legacy.”

Beyond the horror of what happened to these women, Moore says her readers have already found a positive message in “The Radium Girls.”

“It’s a story that gives hope and courage that in the face of implacable resistance and you know, the authority shouting down these people, these ordinary people who are fighting against injustice,” she says. “The Radium Girls did triumph. They did get the laws changed. They did make people see right from wrong, and so it’s the story that can give hope in these times as well, that when we bond together as the Radium Girls did, you can make change happen.”

She adds, “That’s what I really want readers to take away as the message. Read the book, remember the girls and let’s be brave like they were.”

Thank you for your excellent interview of Kate Moore and your review of this powerful and timely book. I thought I knew the story. But Kate Moore’s meticulous research and empathy has created the first book to really capture both the New Jersey and Illinois stories.

I plan to read this book as soon as it becomes available via my local public library. While I know it won’t be ‘an easy read,’ I am sure it will be a worthwhile one….especially in these times where Trump and his cohorts want to roll back many regulations.

The US Radium Corporation plant where the radium girls worked was actually in Orange, NJ, just a couple miles from where I grew up. The abandoned factory became a superfund site. Soil tainted with radioactive tailings was used for fill at a homesite near my house. The house was later lifted so all the dirt could be dug out and removed and the neighborhood cordoned off, but you couldn’t undo the damage already done!