Wherever you look for PFAS, you’ll find them.

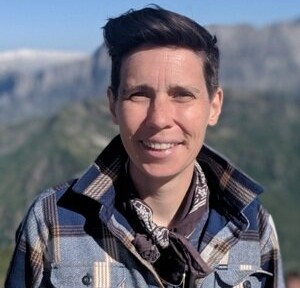

“They’re on Mount Everest; they’re in the Mariana Trench; they’re in polar bears; they’re in penguins; and they’re in just about every human population on Earth,” says David Bond, a cultural anthropologist and professor at Bennington College, who’s been investigating the “forever chemicals.”

PFAS (perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances), a family of chemicals that includes PFOA and PFOS, are widely used in the manufacture of plastic products like non-stick pans, food packaging and waterproof clothing, and are also a component of firefighting foam.

Their non-sticky, nonreactive properties made them appealing to plastics manufacturers. But they’ve proved a nightmare for environmental health because they don’t break down quickly, if at all. They also travel long distances and bioaccumulate in plants, animals and people. Traces of the chemicals — many known to be harmful — are now found all over the world.

Seven years ago water tests revealed PFAS in Hoosick Falls, New York, just down the road from Bennington College. Bond, along with a small team of other professors at Bennington, began engaging students and community members in an effort to understand the extent of local PFAS contamination — which he later learned even included his own backyard.

They’ve since extended their work to other areas — helping to generate research that’s given communities a weapon to fight back against polluters and push for stronger regulations.

The Revelator spoke with Bond, who also serves as the associate director of the Elizabeth Coleman Center for the Advancement of Public Action, about the dangers of PFAS, why regulators have been slow to act and the power of a real-world education in environmental justice.

You’ve studied the effects of fossil fuels on communities for years. How did you get involved with PFAS?

PFAS came to us. In Hoosick Falls, New York, which is about seven miles from us at Bennington College, a resident discovered high levels of PFOA in drinking water in 2014. The state was unsure of what to do and actually put out a sheet for residents that said that PFOA was detected in the water over the level that the EPA had issued a health concern for, but residents could continue drinking the water and there was nothing to worry about.

So this caused a lot of alarm and residents reached out to me and asked if I would help them understand what was happening. I quickly enlisted a chemistry professor and a geology professor to join me.

We realized that one of the things that we do — teach — could be put in the service of this sort of unfolding toxic event. So we put together a classroom that was free for the community — anybody could come and take that class to learn about the contaminants, the health concerns, and what sort of things were available to help protect themselves.

What was the response from the community? And what did you learn together?

We had about half students and half community members in most of the classes. In 2015 [when we started] it was really just an emerging issue and there wasn’t a lot of reliable information. There were three plastics plants in town that were suspected and found to be the sources of the contamination. The state set up a perimeter around [them] and wasn’t willing to test beyond that perimeter.

But in our class people would say things like, “I live outside town, but every night for a few years, a truck would come up my road with a bunch of barrels and it would come back down the road in the middle of the night with no barrels. I wonder if there’s a dumpsite there.”

And so we would put together a little research question and go up and take some samples from surface water and groundwater where they had identified [potential problems] and see what we found. And a handful of times we came back with really high levels that we then turned over to the state and asked them to expand the perimeter. That perimeter kept expanding.

Eventually what we identified was an area of about 200 square miles that was contaminated with PFOA — way above what you’d expect in that area — that we could trace back to the plastics factories.

It took the state a very long time to start thinking at that scale. But we were able to because we were talking to people, listening to what they said. This is what anthropology is good at — listening to people. And [because we] partnered with a chemist and a geologist, we had all the tools you need to take people seriously and really test what they were telling us.

What’s been the impact of this work?

The students have gotten really engaged with this issue. It’s not something that you study in a textbook yet. It’s an unfolding problem and it’s happening next door. We brought our neighbors into our classroom, and we got out and went into our neighbors’ houses and started working together with them. And the students have been really taken with this model of learning.

I’ve also just drawn tremendous inspiration from how the community has insisted on justice for them. I’m not just working with them, I actually live there. PFAS was found in my own garden.

With this class of chemicals there’s no going back to before — the contamination is so extensive. There’s no way to remediate 200 square miles of this contaminant. It means that people are going to be carrying a lifetime of medical worry.

We know that trace exposure to these chemicals on levels of parts per trillion — which is almost impossible to get your head around how small that is — is strongly linked to a number of developmental dysfunctions, immune issues, and a host of cancers. Folks know these chemicals are in our community. We were exposed to them for decades. That means we’re going to have a pattern of health impacts over the long haul. So they’ve been really proactive at insisting that medical monitoring be part of any settlement with the polluters.

That sets up a kind of infrastructure where all the local doctors and nurses are on the lookout for all of the health issues that are known to be associated with exposure to these chemicals. And most of these issues — if they’re caught early — they’re very treatable.

Folks have also insisted on filtration systems for everybody’s water — this stuff is probably going to be in the groundwater for millennia.

After working in Hoosick Falls, you’ve extended your work to other communities. What else have you found?

In the last few years we’ve gotten a number of requests, and each time we try to figure out what we can do to help and how we can put the scientific resources of a college to work helping the public understand the PFAS issue and equip them to be better citizens and pursue environmental justice.

The last one that we got involved in was the incineration of PFAS. As it’s becoming clear that they will likely be designated as a hazardous waste substance, those who are sitting on stockpiles of these chemicals will soon have a huge liability on their hands. So the Department of Defense and the petrochemical industry have all rushed to start trying to incinerate stockpiles of PFAS.

This is worrisome because there’s no evidence that incineration destroys these chemicals. They’re fireproof toxins and are used in firefighting foam extensively. It’s a bit of a harebrained notion that you can burn them to destroy them.

A public housing complex in Cohoes, New York got ahold of us two years ago. It’s next to an incinerator. They had gotten word that it was suspected to be incinerating a tremendous amount of what’s called AFFF [Aqueous Film Forming Foam], which is a firefighting foam that’s made mostly of PFAS chemicals.

We took some samples of soil and water around that incinerator and analyzed them. We found a fairly distinctive fingerprint that matched AFFF. And again, in the shadow of the incinerator stands the public housing complex that’s by and large poor people of color. And this incinerator was just torching away as much PFAS as they could get. There’s no evidence that incineration was breaking those toxins down and good reason to think it was just spreading them into the community.

We were able to document that and push that out and the town passed a moratorium on burning PFAS waste at that incinerator. And then the state passed a bill that banned this incineration in [parts of] New York. We suspect that hasn’t slowed down the burning of these chemicals nationwide, so I’ve been in conversation with a few folks trying to figure out how we can push a national ban.

There has been recent news that the EPA is finally moving to act on regulating some PFAS. Do you think the actions will go far enough?

I appreciate that the EPA is taking a step toward this crisis by announcing that they are going to begin to try to regulate PFOA and PFOS — two of the most prominent chemicals in the PFAS family. However, the step they’ve chosen to take is far too little and far too late. The EPA was made aware of the toxicity of PFOA and PFOS nearly 20 years ago.

If you follow that timeline out, it’s going to take about a century to go through all of the PFAS chemicals that are now in circulation, build up a data set on them, and begin to issue regulations for them.

And now that we’re discovering these chemicals in our drinking water, our farms and our bodies, [regulators are] almost throwing their hands up at the sheer ubiquity of the problem and saying, “What can we possibly do at this point, they’re everywhere”? It’s almost as if PFAS are becoming too toxic to fail.

The petrochemical manufacturers knew the risks of these chemicals almost from the moment they started manufacturing them in the 1960s. Again and again, they buried that evidence. The ways that PFAS has made a mockery of our environmental regulations can’t be the end of our ability to prosecute these injustices. This needs to be the starting point of fixing everything that went wrong, not a point of resignation.

Previously in The Revelator:

Are Forever Chemicals Harming Ocean Life?

![]()