This has already been one of the hottest summers on record, and things are only going to get worse. Unless we do something about it.

So … let’s do.

We can’t really go to the beach in these final few weeks of summer — too many potential disease vectors walking around in Speedos — so let’s all stay home and read up on climate change.

We’ve collected this summer’s 10 best new books about global warming and related topics — all published over the past three months — covering how we got here and how we’re going to get out of this hot mess. You’ll find books about science, activism, history and people, and even some art along the way.

And maybe you’ll also find some inspiration.

The Future Earth: A Radical Vision for What’s Possible in the Age of Warming by Eric Holthaus

The Future Earth: A Radical Vision for What’s Possible in the Age of Warming by Eric Holthaus

Billed as “the first hopeful book about climate change.” Holthaus, a meteorologist turned climate journalist, explores several major scenarios under which we could get to carbon-zero over the next three decades and save the planet. Along the way he also encourages another radical idea: that we relearn how to embrace the Earth and our relationship with it — and maybe our relationship with ourselves along the way.

Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It by Jamie Margolin

Youth to Power: Your Voice and How to Use It by Jamie Margolin

An essential book by one of the country’s most engaging young climate activists. Margolin cofounded the action group Zero Hour and helped energize 2018’s record-breaking Youth Climate March. Now she shares her experience and expertise — along with that of other activists — and offers advice on everything from organizing peaceful protests to protecting your mental health in a time of crisis. Greta Thunberg provides the foreword.

When the World Feels Like a Scary Place: Essential Conversations for Anxious Parents and Worried Kids by Abigail Gewirtz

When the World Feels Like a Scary Place: Essential Conversations for Anxious Parents and Worried Kids by Abigail Gewirtz

A wide-ranging book by a child psychologist that teaches parents to help stressed kids of all ages deal with the world’s ever-growing multitude of crises, ranging from climate change to active-shooter drills — and yes, COVID-19. Oh yeah, and along the way the book aims to help parents deal with their own anxieties about these issues.

Disposable City: Miami’s Future on the Shores of Climate Catastrophe by Mario Alejandro Ariza

Disposable City: Miami’s Future on the Shores of Climate Catastrophe by Mario Alejandro Ariza

Environmental and economic collapse go hand in hand for Miami, Florida — and this book provides a poignant first-person investigation into a metropolis that could one day soon be underwater. (Read our full review here.)

Health of People, Health of Planet and Our Responsibility: Climate Change, Air Pollution and Health

A wide-ranging, open-access (as in free) academic book addressing how climate change damages peoples’ health, covering everything from the cardiovascular effects of air pollution to the ethics of climate justice. There are even chapters about how the climate crisis will affect our mental health and religious faiths. Edited by Wael K. Al-Delaimy, Veerabhadran Ramanathan and Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo, with dozens of contributors from around the world, the book is available for download in its entirety or on a chapter-by-chapter basis.

Who Killed Berta Cáceres? by Nina Lakhani

Who Killed Berta Cáceres? by Nina Lakhani

This isn’t exactly a climate book, but it’s a must-read and close enough in topic to belong on this month’s list. Subtitled “Dams, Death Squads, and an Indigenous Defender’s Battle for the Planet,” this powerful investigation digs into the brutal murder of an activist who led the fight against a hydroelectric dam being built on her peoples’ sacred river in Honduras. In an age when hydropower is being embraced in some corners as a low-carbon alternative to fossil fuels, we need to remember that dams are often built on blood and stolen land.

Paying the Land by Joe Sacco

Paying the Land by Joe Sacco

The author, an acclaimed journalist/cartoonist best known for his graphic novels about war zones, travels to a different kind of conflict: the fossil-fuel and mining industries’ destructive influence on a First Nations community in the Canadian Northwest Territories. Heartbreaking and powerful, this book drives home that the climate crisis was affecting people long before temperatures started to rise.

The Next Great Migration: The Beauty and Terror of Life on the Move by Sonia Shah

The Next Great Migration: The Beauty and Terror of Life on the Move by Sonia Shah

Climate change is already forcing people, animals and plants to shift where they live — an often-dangerous prospect fraught with potential consequences and conflict. But is migration also a solution to the climate crisis? Shah looks deeply into human and natural history — not to mention our history of xenophobia — to show how we can effectively embrace compassionate laws, wildlife corridors and permeable international borders to benefit a changing world.

Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World edited by John Freeman

Tales of Two Planets: Stories of Climate Change and Inequality in a Divided World edited by John Freeman

In this hybrid book of nonfiction, fiction, essays and poems, an all-star lineup of international writers addresses how climate change will exacerbate the gap between rich and poor around the world and put millions of people at greater risk. Margaret Atwood, Anuradha Roy, Lauren Groff and Chinelo Okparanta are among the notable contributors.

The Hidden Life of Ice: Dispatches from a Disappearing World by Marco Tedesco

The Hidden Life of Ice: Dispatches from a Disappearing World by Marco Tedesco

A noted climate scientist takes us on a journey to Greenland to discuss its melting beauty and the secrets that researchers are uncovering beneath the ice. Part science book, part history lesson, part travelogue, this book puts the reader on the front line to illuminate the climate crisis and what we’re losing in the process. Co-written by journalist Alberto Flores d’Arcais; Elizabeth Kolbert (The Sixth Extinction) provides the foreword.

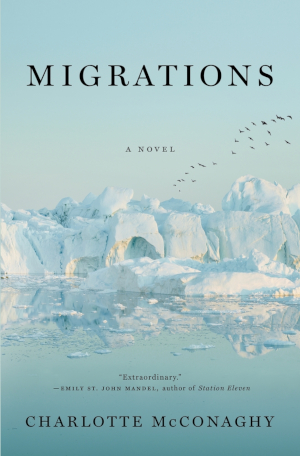

Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy

Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy

A near-future novel about a world almost destroyed by climate change and overconsumption, narrated by a woman whose dark secrets and haunted past echo the melting ice and extinctions that surround her and a ship’s crew as they follow the final migration of the world’s last surviving birds. Mysterious and melancholy, but as much about the quest for the future as what the characters have lost.

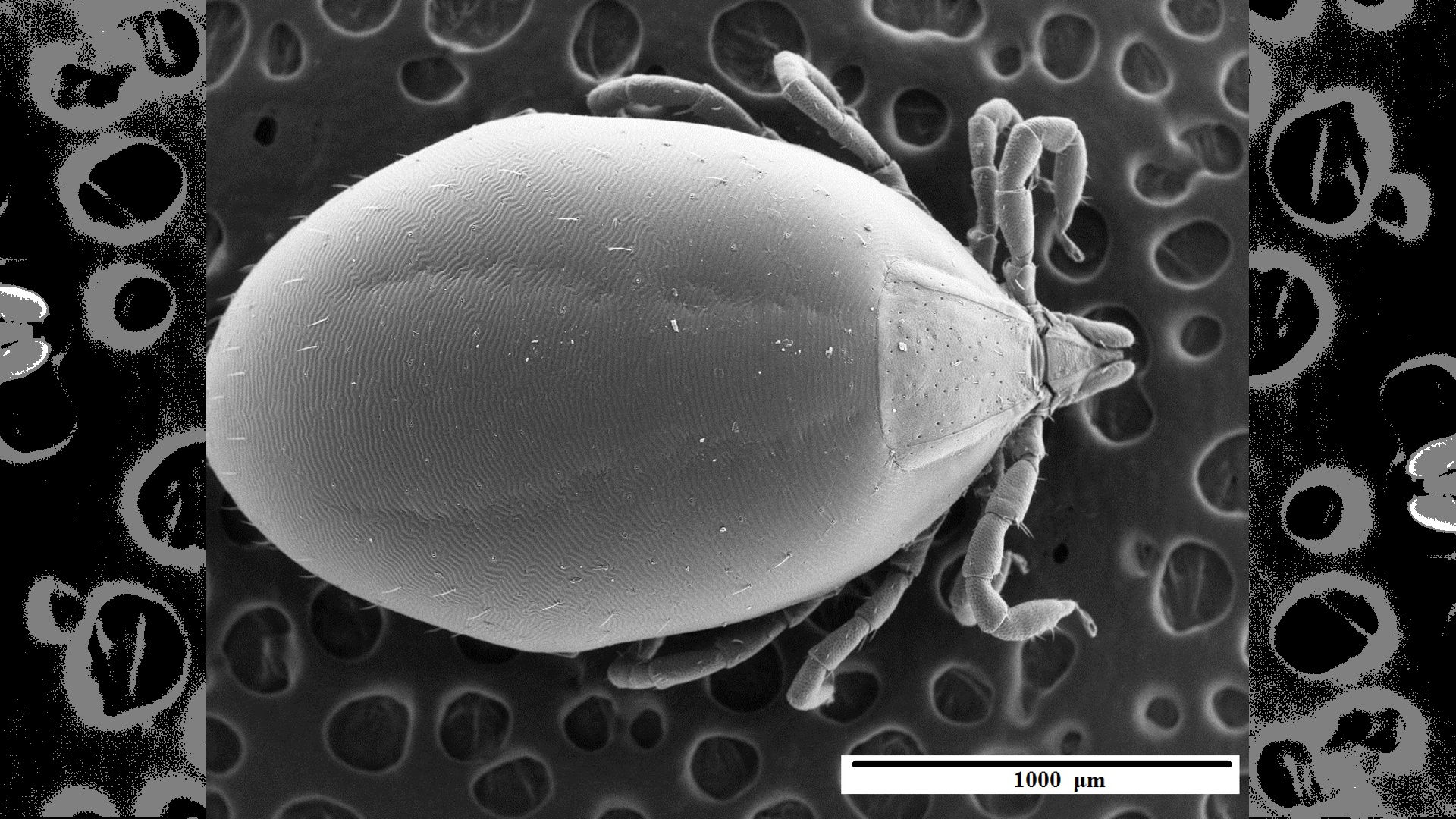

![]()